Caldwell, ID. Form matters. “I love you” accompanied by flowers may be a kind gesture on any given day. Delivered the day after a forgotten anniversary, flowers are damage control.

It is not only the content of what we say or do that matters, but also the forms and liturgies surrounding words and actions. Whether The Office’s Michael Scott says or declares bankruptcy makes no difference apart from the proper legal form. Promising your undying love lacks significance without the formal marriage ceremony. Even teachers who teach such connections can forget that form matters. Much attention has been given to what we should learn while glossing over the habits or liturgies that should form the Christian student.

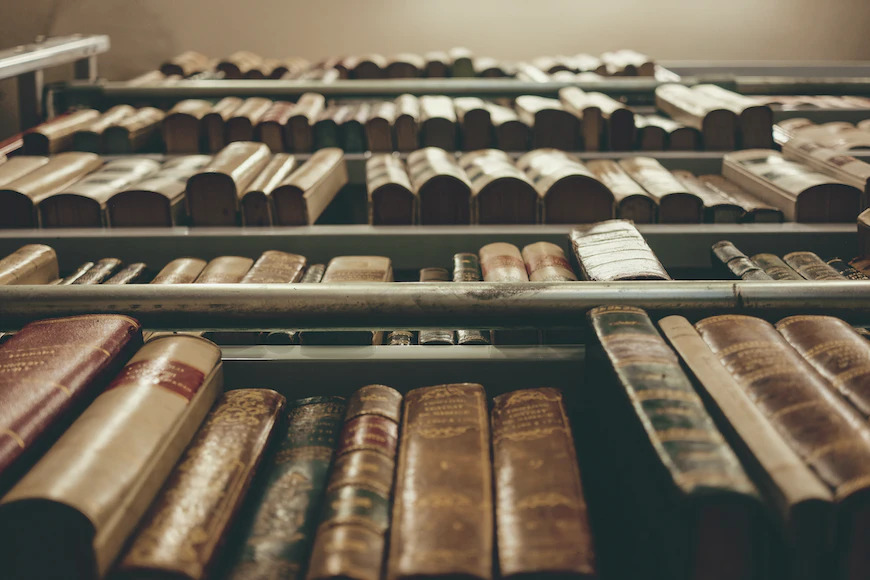

While there are anthologies of great texts or collections centered around the content of the great tradition, Jessica Hooten Wilson and Jacob Stratman aim to provide a resource on “what it means to be a Christian learner” with their new book, Learning the Good Life: Wisdom from Great Hearts and Minds that Came Before. How does the wisdom of the past not only shape the what but the how of learning? Wilson invites readers to imagine themselves in the apocalypse stumbling across a book containing pages from the greatest minds and hearts who have ever lived calling their readers to a life of learning, thinking, and loving. This book aims to be that resource that shows how to learn as a Christian.

Coaching requires models. From the earliest stages, parents train their children by saying, “Watch me; now you try.” Athletes imitate professionals to hone their technique and improve their form. It is the same for learning to be a learner. We watch the masters to become like them. We not only heed their teaching but imitate their life. This book is a portal to time-tested teachers whose wisdom transcends our present concerns. By spending time with them, perhaps we can become more like them in our efforts to learn. Much like James K.A. Smith’s cultural liturgies project, this book aims to provide formation rather than merely information.

Because this type of imitation isn’t so much taught as caught, the work concludes with a litany of prayers to be offered before study. This fittingly reorients the reader the purpose of the book—to teach us how to study and learn as Christians. Adopting the habit of praying these before intellectual endeavor would do more to shape Christian affection and discipline in study than hours of study unaided by the Spirit. I would encourage anyone reading this volume to begin here. Start by absorbing and repeating these well-constructed prayers of the saints and let yourself be shaped by them before reading each selection. This is not a competition between prayer and study (cf. B.B. Warfield) but a recognition that learning is a spiritual pursuit, and we ought to study by prayer.

Why is it that academia is perceived as taking more than it gives? Picture bleary-eyed college students sitting lifelessly through lectures, turning pages in their textbook, then dutifully regurgitating information onto an exam only to walk away unchanged. What should be an instrument of life—a movement from knowledge to belief to action—becomes soul-stultifying drudgery. Why? It is because we have not given attention to the practices of mind and body that befit a student. Lying on a bed at 2:00 AM idly flipping through a book while texting a friend isn’t likely to be a transformative experience. Treating education as a hoop to jump through to secure a job, make money, and consume leads to practices serving that end.

The authors in this book will challenge our perceptions about what learning is for. Confucius urges us to sacrifice and show piety, and attend to our obligations (Ch. 2), Plato turns our eyes from the dusty earth to a glorious vision of unifying, illuminating truth (Ch. 3), and Gregory encourages a love of truth, goodness, and beauty expressed through pleasing verse (Ch. 6). Learning is a duty as necessary as fighting a war for it offers an avenue to Divine beauty to enjoy and share with others (Ch. 35). An education offers us a chance to get beyond ourselves and consider the story behind every face we pass—prompting us towards sympathy and understanding as we move through water (Ch. 41).

But all of it is just another stack of papers to be filed away and never used if we do not prayerfully reform our practices. We become the patient nodding along as the doctor proscribes an exercise regimen he has no intention of following. This is not a book to be read quickly. As you read, look in the mirror and examine your practices. If you believed what you read, how would your habits change? What would you need to do for these truths to become medicine and not poison? But you are not alone on the journey. This book contains records from men and women who have struggled along the same path. While spiritual powers have knowledge stretching back to the beginning, humans begin their short lives with nothing. Any progress we hope to make must build on the labor of the past. So carry the fire.

Many of the selections will be standard fare for those acquainted with the great tradition or classical education—Athanasius, Augustine, Dante, Milton, Shakespeare, and Sayers are all represented. There are some lesser known (or at least less often read) authors whom I was delighted to be introduced to, such as John Comenius, whose allegory the forward uses to illustrate the dangers of learning. Nor are all the authors Christians; Plato, Seneca, and Nietzsche are represented, as well as authors outside of Western education: Lao Tzu or Confucius for example. Christians have a long tradition of receiving wisdom wherever it may be found, and these authors provide a welcome cross-cultural breeze testifying to common grace. The scholars introducing each section ably demonstrate what they have to offer the Christian about learning for God’s sake.

The selections are divided into four time periods, with roughly the same number of selections for each period. The first section roughly corresponds to what many would call ancient history (450 BC – AD 600), and then medieval (AD 600-1700), early modern (AD 1700-1900), and modern (AD 1900-Present). The largest section was from the last century (even including still living authors). This gives an unfortunate bias to the modern period for a book which aims to collect from those who “managed to articulate insights that lasted long beyond their lifetime” (xiv-xv). David Foster Wallace, Marilynne Robinson, or Wendell Berry certainly have something to teach us about learning, but we ought not to yet give them the same respect as those whose wisdom has endured testing for millennia. In “Learning in War-Time” (Ch. 35), C.S. Lewis implores that “most of all, perhaps we need intimate knowledge of the past. Not that the past has any magic about it, but because we … yet need something to set against the present.” Heeding Lewis’s advice would unfortunately mean less Lewis, but I think this is what he would prefer. C.S. Lewis became the scholar he was because of his archaic devotion to the past. His vision extended beyond his generation because he learned universal truths about human nature from dwelling on the enduring.

I confess it is difficult to review anthologies, particularly collections of classic authors, because most of the authors have already submitted to the judgment of history. Further, although they speak on the same subject, they are not a single author nor are their entire works reproduced here. Thus, the reader must take these short selections as an invitation to read the author in his own, unedited words.

It is easier to critique the contributing writers, though these should be considered the garnish rather than the main dish. Each excerpt is introduced by a scholar, who occasionally also provides the translation of the work. These introductions serve to orient the reader to the selection as well as make didactic application to the life of the student. These helpfully orient the reader to new authors as well as prime the heart for what it should receive from the reading. Further, each section contains questions for reflection which serve to direct the student in learning well. All of these focus the selections on the purpose of the book—training the Christian student for a life of service.

If there is one discordant note, it is the introduction to a passage from Jarena Lee, a nineteenth century African Methodist Episcopal preacher. The excerpt from her Religious Experience and Journal focuses on her defense of women’s ordination. Scholar Patricia Brown uses her introduction to defend Lee’s argument, a claim which all the Christian theologians and authors cited earlier in the book would have opposed. Brown writes as if any opposition to the ordination of women is simply a matter of misogyny and fear of change, rather than a position grounded on hundreds of years of Christian tradition and the several passages of Scripture upon which that tradition rests. Though it should be noted that a follow-up question asks readers to evaluate Lee’s scriptural argument, the chapter seems like a lost opportunity. What else might Lee have to offer modern Christian readers besides a simplistic morality tale about how a “multiminoritized” woman used “nonconventional interpretive strategies” to “contribute to a growing discourse of freedom and empowerment”? Reading even an excerpt from Lee suggests she may have balked at being described in such sterile academic cliché. Besides, PBS has that part of her story covered for us already. How about searching Lee’s writings for something from Lee that is not safe for consumption by the good viewers of PBS?

Quibbles aside, this volume would be a welcome gift for any student who finds himself asking, “what is it all for?” Any resource that directs us to the wisdom of the past and thoughtfully guides our reading is a refreshment from modern drivel. Further, this book successfully fills the gap in current resources by providing a text on how we should learn, rather than merely what we should. We need more scholars who are dinosaurs. They not only know the tradition, but they have breathed its air, walked its shores, tasted its depths.

Learning the Good Life is not just an invitation to know certain things, but to live in a particular way. It teaches us how to approach the task of learning by presenting rich ideas to contemplate the Divine and challenging our presuppositions. By it we learn to practice charitable disagreement and pray our way through a difficult text. If treated like another academic exercise of cramming before a test, Learning the Good Life is just another textbook; if viewed as an invitation to walk alongside those who have made the journey, it promises to transform our habits as students.