Buffalo, NY. I can’t recall when I read Wendell Berry’s 1970 essay The Hidden Wound for the first time. But, as a white male from rural north Alabama, I do remember the effects of that initial reading. While my own rearing several decades later didn’t exactly mirror the one described in the book, Berry’s experiences of the far-reaching effects of racial prejudice, racial thinking, and the construction of identities of “race” resonated.

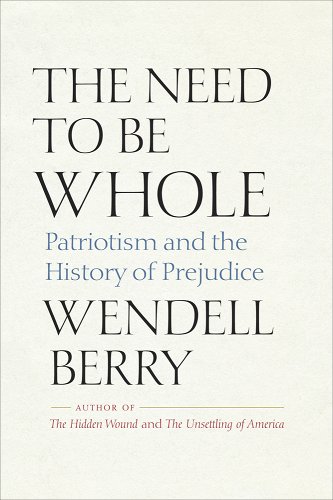

Since that first reading, I have re-visited the volume personally at least five times and taught it to students at both Canisius College and the University of Kentucky three other times. Perhaps because of my own scholarly interests and training, it stands as one of my favorite of Berry’s essays. I must admit, however, that I have always struggled with satisfactorily locating The Hidden Wound within and alongside the Kentucky farmer’s other writings. The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice alleviated (or at least begins to alleviate) that struggle. Despite some imprecision in his treatment of the ways “race” intentionally serves to limit and to define others, Berry situates the thoughts from his earlier essay on prejudice and racial thinking more fully alongside the other major themes of his thought, offering his readers something of a whole tapestry of his ideas.

Perhaps one of my favorite parts of The Need to Be Whole is Berry’s tone of humble conversation. He isn’t trying to present himself as an expert on the subjects of patriotism, nationalism, prejudice, and racial thinking. Rather, he writes as a dedicated student engaged in a hopeful conversation. Such an attitude seems more than fitting for one who in 1977 wrote “The teachers are everywhere. What is wanted in a learner.” His yearning for a learning conversation, however, doesn’t always serve the argument as well as I hoped.

As a scholar of the intersections of religious ideologies and racial identities in early America, I noticed this issue most in Berry’s lack of precision when defining central concepts, such as “race.” This imprecision, in my estimation, keeps Berry from seeing some of the ways that the white Americans about which he writes constructed “race” as a means of describing differences between themselves and the people of color around them. For instance, on several occasions Berry perhaps underestimates the effects of “race” in Henry County because of his overemphasis on the fact that Black and white men and women regularly performed the same work. As I argued in Race and Redemption in Puritan New England, white New Englanders regularly used “race” as a way both to elaborate on and to define perceived differences between themselves and the people of color with whom they regularly worked at the same jobs, lived in the same homes, and worshipped in the same congregations.

A similar dynamic nearly certainly existed in the Henry County about which Berry writes in both The Hidden Wound and The Need to Be Whole. Recognizing the ways that white men and women used and constructed a sense of their own whiteness as a means of creating solidarity or even a notion of patriotism (to fit in other parts of Berry’s analysis in his latest volume) would likely help explain the race relations and racial prejudice he treats. For this reason, in my estimation, a fuller definition of “race” would further elucidate and complicate the legacies that he documents and explores so well.

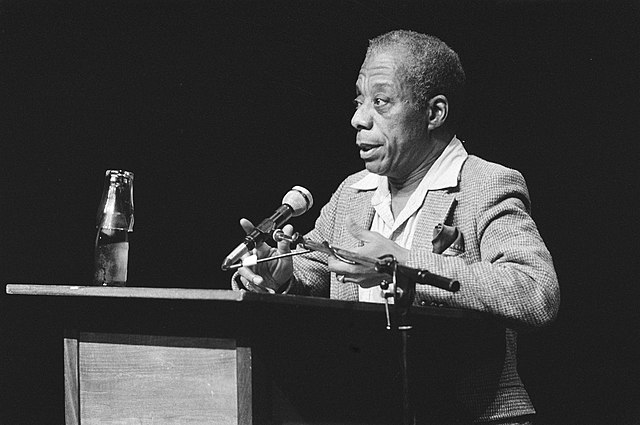

Once again, however, readers of this new book would be served by revisiting Berry’s earlier efforts to explore the legacies of racism in The Hidden Wound. This book was also written in a fraught cultural moment, the late 1960s (a few years after befriending Ernest Gaines and in the middle of the civil rights movements), and it focuses on Berry’s personal experiences with Black men and women living in Port Royal, Kentucky. With emphases on affection, place, community, and work, he cogently explored the effects of racial thinking on the psyche of white Americans. In the vein of similar essayists of the 1960s, especially James Baldwin, Berry clearly admitted the pains inflicted on African-Americans. But his treatment of the ways racism has affected many whites was the main focus of his extended essay. And, to this white reader who grew up in a community with a sizable and significant Black population, this portion of the essay was both convicting and convincing as he encouraged me to consider the hidden ways racial prejudice had affected my life and world view in ways I rarely recognized.

Even though I found Berry’s analysis of many white experiences of racism fairly true to life (or at least my life), I always struggled to connect the essay to his other writings. As anyone familiar with Berry’s essays and fiction following The Hidden Wound knows, he has regularly expounded on themes such as affection, community, industrialization, and place. Even though these themes are in his 1969 essay, I always struggled to grasp how to fit issues of “race” into his overarching narrative. Instead, I saw the economy and lifestyle toward which he encouraged his readers as one primarily directed toward and likely appealing to a white audience. But that line of thinking clearly moved against the tenor of The Hidden Wound. And the book was well-received by various Black readers, in particular Berry’s fellow Kentuckian bell hooks. So, I wrestled with how to make those connections, usually pairing Berry’s work with various essays by James Baldwin, such as his “The Fire Next Time” and “The White Man’s Guilt,” in my efforts to do so.

All of that changed following my reading of The Need to Be Whole as Berry connects these major themes from The Hidden Wound to other themes from his many works—work, agrarianism, industrialization, citizenship, affection, and place. In so doing, he offers his readers a fuller-orbed view of his thinking than maybe he has ever done previously. In the end, at least after my first close reading of the volume, I think this work of integration is the most valuable contribution of The Need to Be Whole. He admits an ignorance and a willingness to continue learning, echoing the following lines from his poem “Healing”: “In ignorance is hope. If we had known the difficulty, we would not have learned so little. / Rely on ignorance. It is ignorance the teachers will come to.” This willingness to learn and reliance on hope allows Berry to refine the image of American life he has painted for over nearly sixty years, making it more panoramic, complete, and whole.

Image Credit: Vincent Van Gogh, “Wheat Field with Mountains in the Background.”