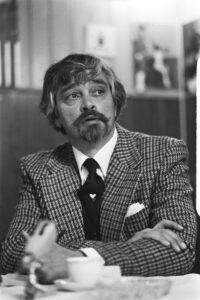

Groningen, Netherlands. In the early 1980s, while listening to his great-aunts and -uncle reminisce about provincial life around the dawn of the twentieth century, Dutch illustrator and painter Rien Poortvliet (1932-1995) came into possession of his family tree. Tracing back his ancestry to the late fifteen hundreds, he paints an intimately human and wonderfully down-to-earth picture of his forefathers and their daily lives. Innumerable sketches of the Poortvliet family, as imagined by Rien, fill the pages of his illustrated book Langs het Tuinpad van mijn Vaderen (Along the Garden Path of my Fathers, published in 1988 as In My Grandfather’s House)—a clever play on lyrics from a 1974 song by Wim Sonneveld, “Het Dorp,” about the tragedies of modernity and a nostalgia for the simpler times of his childhood. Langs het Tuinpad is an account through ten generations of hard-working, hard-drinking and hard-praying men and their wives, of hardship and glee, all bound together by firm roots, family, and the waterlogged islands of the provinces of South Holland and Zeeland. Its title page sets the scene with a drawing depicting a line of men, each presenting himself to the reader, one after the other, growing steadily smaller into the distance.

The book is organized chronologically in the opposite direction, starting in the present and walking back in time, keeping the thread in hand. He begins with his own memories of visiting his great uncle’s house on the island where his family had lived for 200 years. Grandpa left the small village of Dirksland on the island called Goeree-Overflakkee (Flakkee for short) for Rotterdam around the turn of the century, so Rien grew up in the big city. His great uncle lived in the country, in a house no more than a stone’s throw away from where he was born in 1880. Rien visited only once, in 1944 at the age of six, but he never forgot certain quaint and, even in the ‘80s, seemingly antiquated, customs and habits: How the steam-powered tram would slow down crossing the little canal bridge if the driver saw you fishing from the next bridge over so he could wave good morning; How that other bridge was so poorly designed you could never walk over it comfortably with your bike by your side—only the wildest daredevils dared crossing it while cycling; How the sounds of owls and horses rang out during the otherwise perfectly quiet nights; How the boys pelted each other with horse droppings. Most folks there still lived off the land, tilling it, walking behind their horse-drawn plough in the pale orange light of the morning, clogs on their feet, cap on their head. Lying in bed at night, Rien couldn’t help but thinking about how his own father would spend his vacations sleeping in the same bed. “Not much had changed in the previous sixty years,” Rien tells us. “Maybe the road had been paved, but that was about all.”

For Rien’s grandfather, Marinus, to “emigrate,” as he calls it, to Rotterdam was a momentous decision. To most on Flakkee, the mainland was a totally different world. Rien imagines (grandpa died when he was only five) that when the steamboat set off and his father and mother waving him goodbye on the quay shrunk away in the distance, it must have felt like a grand adventure, travelling to unknown lands. Rien writes of grandpa, “the young emigrant, through filthy and noisy streets, tries to find the way to his little room . . . And there he is at the end of the day, a farm boy in some sort of backroom, three floors up. He’ll do his best to learn to speak proper Dutch – too often, the people there chuckled at him when he asked for directions. And when he looks out of his window before going to sleep, the snow [he remembers from home] has disappeared.” It paints quite the picture: a man, lost in a foreign land while his own people back home huddled around a petroleum lamp on the table by the red-glowing hearth with a cup of steaming coffee. Marinus, meanwhile would lie in his strange bed thinking of the little street where he grew up and did the groceries for the old lady living next door. A group of women would keep him up at the baker or the butcher or the grocer, asking for the latest village-gossip, before the clerk recognized the boy and called him over, releasing him from the clutches of every small town’s worst nightmare—gossiping housewives. Most days were like that, except Sunday, of course, when everyone set out for church early in the morning—some from their cottages in the countryside, many miles away.

But it wasn’t all romantic – nothing is. Young boys, often no older than ten, would get up before even the rooster did, don their caps and boots (or clogs) and walk—sometimes for over an hour—to the farmer’s pastures to look after his cows. Each day when there was no school (and sometimes when there was) he’d get up at 5:30 and return home at 6 the next evening. No matter the weather, he was charged with oversight and making sure the animals didn’t wander off. The girls, meanwhile, often acted as “help-mother,” taking care of their younger siblings when mom went off to town—or when she went off to the grave. If father was a fisherman and mother was dead, the teenage girl would be all alone for weeks, in charge of four, five, six brothers and sisters. Even when she came home from school, there were more household chores waiting for her. Besides that, there were plenty of children who “could barely read or write, because of poverty—so often they had to skip class to work on the land . . . he’d leave for home at the end of the day with some meagre cash and a bag of dried grass for his rabbits (whom he didn’t keep for fun).” If it rained that day, he and father would dry their clothes at the hearth or on the stove; they only had one set. More often than not, such a life would earn you little more than a hunchback before you were fifty. Most people on Flakkee worked off the land, sowing and reaping and sowing again. It was a hard life, it was an unromantic and unglamorous life; but it was an honest life, and a life of belonging and home. The people knew each other, and they belonged with each other.

Some lovely practices emerged from such a life as well. Almost everyone kept a pig, for example: “You couldn’t do without; it was [literally] your piggy bank, the family capital and your voucher to survive the next winter.” Each time family or friends visited, they would want to see your pig first. And there were ways of dealing with a sick-looking pig: “Sometimes, when disease roamed around and your pig didn’t look so fresh—the meat didn’t get inspected or anything—the best course of action was to slaughter it preemptively and give a piece to some village idiot or other and observe him for a few days.” Ethical? Not really. But a great example of naturally grown traditional wisdom? Certainly.

Grandpa Marinus couldn’t get Flakkee out of his thoughts. He often wrote to his parents back home, asking if anything exciting was going on; there never was. Around 1900, this trusted country life was gone in Rotterdam, so when he couldn’t sleep in the unquiet nights he’d draw sketches and paintings of scenes from his childhood village. He’d often take jobs plastering houses on the island, just so he could be there and visit his family every once in a while.

Rien’s great-grandfather, born a poor farmer’s son in 1823 in the same village of Dirksland, where he’d live all his life, decided to eke out a better living for his children. He became a livestock speculator, walking great distances all across the island (the bicycle hadn’t yet made its way to this far-off corner of the country by the mid-19th century), sometimes more than 40 kilometers a day, to seek out prospects. Life still wasn’t luxurious by any means; his little daughters slept four to a bed. But it was far better than for most. Monday to Saturday they worked; Sunday they went to church, sang hymns, and played cards while the children played outside. The church tradition was very important to great-grandfather, and he made sure his son was baptized in the same font as he was.

From here on out the narrative speeds up. The threads of memory, passed down through four generations, died with the life of his great-grandfather—as it does for so many of us—so Rien solely relies on archival research and a bit of his own imagination to portray his ancestors’ lives. He calls his great-great-grandfather his grandpa (3), that one’s father his grandpa (4), etc. in order to avoid the mess of identical adjectives it would otherwise create.

His grandpa (3), Cornelis, was born in 1787, his parents’ eighth and only surviving child. His bouts of unrelenting sobbing would be stilled by some bread soaked in milk and sugar, wrapped in a towel they’d put in his mouth. Sometimes, if he threw a particularly nasty tantrum, they put brandy or even some seed-opiates in his little towel. Just like Rien did in 1940, little Cornelis watched the occupying army march through the streets—this time a French one. When he was twenty-two, his French-language marriage certificate shows he married a local girl who would give birth to four children in rapid succession; none made it past three years old. He paid his strange French taxes for foreign wars and the number of windows in his house by working as a day laborer for several different farmers. A perfect example of the lunacy of centralized bureaucratic rule from a distant capital was the fact that the French occupiers expected the locals to learn their language, yet they misspelled the name of the village, which according to them was “Driksland” instead of Dirksland, on the officially created postmark. They imposed a French-speaking bureaucratic administration on top of a Dutch populace, who remained utterly bewildered by these figures and their weird hats. In 1855, after having brought his wife and nine of his children to the local cemetery, Cornelis dies as well, having outlived all but two (one of whom would die just five days later).

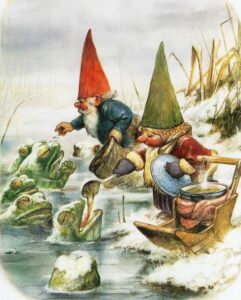

Grandpa (4), Zacharias, was born in 1738 in a day laborer’s family—something the Poortvliets seem to have been since the dawn of time. He survived two terrible winters, where people were too frightened to go ice skating on the frozen ditches and canals for fear of wolves, several livestock diseases, another war with the French, and the death of his mother, all before he was eleven. From that point on he had to help earn a living on the land. Interestingly enough, not only did the Dutch already enjoy ice skating, the tradition of eating oliebollen during New Year’s was already well established as well. In 1781, Zacharias was called up for the “citizen’s guard” — the militia, to protect the village at night from the civil and political unrest gripping the Republic at that time. He’d patrol the pitch-black streets with his rifle and his oil lamp, looking for rabble-rousers, keeping his own town safe.

When grandpa (5), another Cornelis, was born in 1709, he was the first generation to be born in the house where the next four generations of Poortvliets would see the light of day. As a day laborer he suffered from chronic financial shortness – to the point where he married three times using church funds. This church was finally erected in stone during his early life and would be gratefully used by the people of Dirksland to this day. Just about the only knowledge Rien can gather from Cornelis’ life came from the church books; being a simple man he didn’t leave anything behind himself.

A more exciting story, among others the reason why the Poortvliets ended up in Dirksland on the island of Flakkee, was to be reconstructed from the life of grandpa (6), Simon. From his birth in 1684 in the village of Colijnsplaat on an island some 30 kilometers south of Dirksland (less than the distance great-grandfather walked in a day) until his marriage in 1704, Simon seemed to have lived a relatively quiet life. He worked as a day laborer on a farm together with three others, Frans, Pieter, and Frans’ wife Adriaantje.

Long story short, Simon and Adriaantje get a little too close to each other and run off together. Adriaantje disappears completely, and Simon is eventually imprisoned in the provincial capital. Simon swears he just left on his own and has no idea where she is. Eventually he is acquitted of any wrongdoing after Adriaantje’s sister testifies she talked about killing herself using rat poison. Simon doesn’t dare return to Frans, so he leaves for Flakkee and settles in Dirksland. Thus, Rien’s ancestors have lived in the same town for roughly 200 years before his grandfather left. But presumably they have lived in the general area for many uncountable generations prior.

Simon’s father, grandpa (7), was another day laborer on the land, but other than that, there was not much to be found about him. Instead, Rien busies himself with generalities concerning the lives of common folk in the 17th century. The traditional Dutch holiday of Sinterklaas was already celebrated, including children placing their shoes on the floor before desperately singing songs by the window in the evening in an attempt to fall into the Saint’s good graces. What children could learn at schools was the alphabet, basic calculus, and the Ten Commandments – nothing else. Grandpa (7) did own his own home, however. This was a commendable achievement for a man who lives working on other people’s land. Before he bought it, his father, Jan, grandpa (8), already rented that same house. He was born around the same time as Rembrandt in 1606, and his adulthood was during the height of the Dutch Golden Age. The people were ruled by stern and austere Calvinism, imposing frugality, discipline, and ruthless hard work on those who took their faith seriously (which plenty did not).

The muddy streets between their houses were lined with brick footpaths which every household was expected to sweep and clean each Saturday. Neighborhood cohesion did not just evolve; it was enforced. Church attendance was mandatory, and the people addressed each other on their public display of morals. This was not merely a form of control, but also strictly necessary, as drunken violence, roaming bands of brigands, and deadly knife-fights were apparently commonplace. Most men in this little town worked on the land; most shared drinks in the tavern at night; most were acquaintances; some were friends. Grandpa (9), Cornelis Adriaensz, lived a tough life, his livelihood constantly threatened by the ongoing war with Spain. His home was regularly occupied by soldiers, searching for weapons or the whiff of treason. Cornelis supplemented his income by laying dikes to create polders and reduce the numerous small islands of the region to a couple of large ones, during which he was regularly arrested for public drunkenness.

The second to last page of the book contains a partially finished sketch of a man, his face half veiled in shadow, emerging from the mists of time, taking a single step out of the fog to say hello, only to fall back into obscurity and the eternal anonymity that is only granted to those in the distant past. On the next page Rien writes, “My grandfather (10), who was born somewhere around 1560 was called Adriaen. That’s all I know about him—the path ends here.” He only knows his name because his son bore the patronymic Adriaensz, meaning son of Adriaen. He seems almost a mythical figure, a man who lived at the dawn of time; a man who for only a second revealed himself, reaching out for a handshake that passes through 400 years. But Rien never managed to reach quite that far, and he never glimpsed the man he knows only by his name. But of course the line doesn’t end there; it continues on into the past, unbroken, through many more lives that found their origin on those very islands.

Langs het Tuinpad van mijn Vaderen is not a romantic account of better days. It is a straightforward depiction of an unbroken line of inheritance, passed down from father to son, continuing the thread, living where they do. They know their neighbors; they know their village; they know their land. They have their own vernacular that everyone who lives there understands because their father and mother taught them, just like they were taught by their fathers and mothers. The book is a survey of one man’s quest to bring the lives of his ancestors into the light. It is a description of what it is to belong somewhere. In an age that prizes nomadism and the present, this perspective is refreshingly quaint.

Image Credit: Jacob Van Ruisdael, “Wheat Fields,” (1670).

Thanks for this, Henk. Very inspiring.

By the way, the book appears to have been published in English in 1988 with the title In My Grandfather’s House. It’s currently out of print but used copies are not hard to find online.

Comments are closed.