Manchester, NH. The prospect of moving from our little cottage in New Hampshire causes me great pain. Why? Because I am a creature of place and my surroundings, the people, the landscape, the history—all play into my sense of the importance of where I live. This place and its connections form the lens through which I view the wide world. Several authors from other places model the value of such a rooted perspective. As a student in Paris, the poet Czesław Miłosz was dismayed that many of his fellow students disdained their homelands with cosmopolitan condescension. He determined never to disavow the Polish village that he called home. Larry Woiwode’s prosodic engagement with his homeland is evocative of poetry’s best uses—lyric reflections on the pain and beauty of one’s home (Land of Sunlit Ice 2016).

Over the years I have read a number of books about New England life and culture since the founding era. Two of my favorites are Haydn Pearson’s The New England Flavor (Norton, 1961) and The New England Year (Norton, 1966). The former is a series of reminiscences of early twentieth-century childhood rural life in southwest New Hampshire (Pearson was born in 1901). It is nostalgic rather than interpretive, but he portrays an accurate picture of what amounts to an extension of the nineteenth century with horse and ox power, and no electricity. The New England Year recalls the agricultural activities of each month of the year. Recently Corduroy (Faber and Faber, 1930) by an English author, Adrian Bell, covers similar themes as the book under review, Here & Everywhere Else. Bell is farmed out to a country farmer by his aristocratic London father making for some interesting reflections on the differences between early twentieth century urban and rural culture in England.

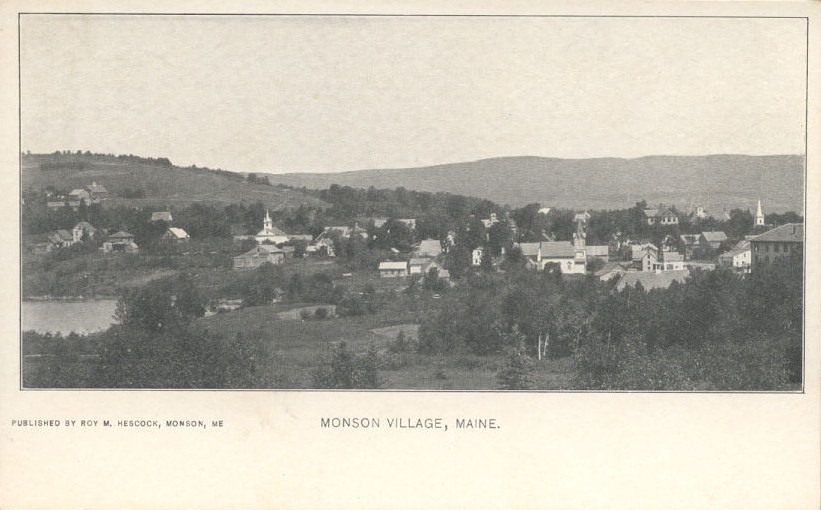

Andrew Witmer’s Here & Everywhere Else is as much a lesson in historiography as it is the particular history of the small rural town of Monson, Maine. It promotes the importance of local amateur histories and suggests that the more global approach of the academic historian depends on the local, but often misses crucial details of local life and culture. What local histories may lack in terms of professional methodology they make up for in terms of personal knowledge. Witmer has provided a fine model for weaving the threads of the big picture into the local historical tapestry.

The Preface reveals the influence of southern agrarian Wendell Berry (x) and humorists Tim Sample and Bob Bryan of “Burt and I” fame (ix). Witmer has an axe to grind, a good one, aimed at sharpening historical perception of rural life over the past two centuries in northern Maine:

Here & Everywhere Else surveys two centuries of momentous change in rural America by exploring the shifting relationship between one small Maine town and the wider world. . . . Although the story includes its share of loss and disappointment, I worked to write a book in color rather [than] in the gray of decline or the sepia of nostalgia, both of which distort our view of the past by pressing us to peer through the lens of the present. (x)

Another thread Witmer weaves into the story is the agency, persistence, and creativity of local people; this prevents readers from viewing them through the grim lens of victimhood. The Introduction sets the local stage for the story, “The View from Homer Hill,” emphasizing the importance of place for the inhabitants of Monson. Witmer states the book’s argument:

rural people have been central actors in the transformation of rural America since the early nineteenth century. . . . Well aware of the challenges of sustaining rural places, Monson residents consistently found ways to strengthen their community by situating it within far-reaching networks. . . . taking ingenious advantage of urban growth, industrial development, and technological innovation. (12–13)

Each of the five chapters has a theme around which local stories are clustered. Chapter 1, “The Paths into Town,” focuses on geography, describing the migration from southern Maine and Massachusetts to northern Maine, along with the disruption this caused for the native population. The many changes in the region took place in the larger context of “international conflict, national integration, and federal dissolution” (12).

After the Revolution many veterans and their families moved to the Maine frontier (18). The surge in settlement put pressure on many tribes in the Wabanaki confederacy (19–20). Since 1500 the European interaction with the natives of the Dawnland (the Wabanaki name for northern New England) was characterized by “coexistence, cooperation, and commerce as well as warfare and disease” (20). Early on the settlers of Monson caused much trouble for the Penobscot tribe. Witmer does an excellent job describing the intrusion with its many complexities.

Witmer weaves the thread of locality’s ties to the outside world throughout the book:

From the economic to the religious, every element of placemaking, every ingredient in the production of locality, involved both ties with the world beyond town and the conviction that those diverse elements mingled in a unique way here. (27)

Road building, the natural resources of the Penobscot River Valley, and logging opened new possibilities for the growing population of Monson, but consequently the fortunes of the Penobscots declined (29). On the other hand, “Monson petitioners sought to ‘free the commonwealth and themselves from all connection with domestic slavery.’” However, the tragedy of Penobscot dispossession is certainly a blot on Euro-American settlement (30).

Witmer covers the important place of religion in Monson life. As early as 1821 Congregational and Baptist missionaries planted churches in this remote new village: “[S]urging evangelical denominations, especially Baptists and Methodists, were pioneering new approaches to religious community. Itinerant missionaries and ministers forged new networks of likeminded believers throughout the region (31). By 1831 Congregationalists built their first meeting house on Main Street (32).

Patriotism also connected local communities with their national identity and unified the people of the town: “Locality was strengthened through celebrations of the nation, rituals of assent that drew (male) residents together, crossing even party lines to manifest shared patriotism” (39).

While fertile western farmlands lured many New Englanders, some also sought modern means to make farming in Maine more profitable. Many reform-minded farmers in this region became convinced that “only modern means (including up-to-date bookkeeping practices, novel fertilizers and equipment, and specialized production for urban markets) would help them meet new challenges and save their way of life” (43).

In the end the relationship between rural and urban culture is nicely summed up by Witmer:

Rurality offered a different path toward progress, one that many northerners believed was more moral than the society of the enslaving South and healthier and safer than the era’s dirty and diverse cities. . . . Country people had a more complex relationship with urban areas than mere fear of scorn. They looked to cities for customers and for cues on the styles and manners that constituted refinement. (45)

Chapter 2, “From Away,” describes industrial development, immigration, and tourism as the locals participated in networks that included the rapid growth of Gilded Age industries along with the rise of Maine tourism.

Gilded Age industrialization involved rural people in a way neglected by most historians. The people of Monson harnessed global and national developments for local purposes (57). Beginning in 1870 Monson began to unearth the riches of slate underneath their feet. Slate shingles became more practical for the slanted roofs of new popular architectural styles like Gothic Revival, Second Empire, and Queen Ann (59). This new industry attracted Welsh and Canadian workers, thus diversifying the Monson population (63).

Tourism began to be a reality for rural places like Monson in the late nineteenth century, representing a healthy escape from the urban environment (67). The Lake Hebron Hotel, like many such accommodations in the New England countryside, became a thriving retreat by 1885 (69). Witmer’s interest in art reveals itself in this chapter. In the mid-nineteenth century, artists and writers, like Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole and author Henry David Thoreau, began constructing a mythic vision of Northern New England as a unique place (72). “[T]he people of Monson dreamed that growth and increased connections with the outside world might transform their town into something it had never been—a place that could retain its own children” (85).

Chapter 3, “Writing Home,” explores the importance of print culture, as Monson residents took advantage of printing presses in Boston, Bangor, and other places to foster local culture, strengthening their sense of place. Witmer excels at portraying individual players in the Monson story. Lawyer John Francis Sprague became the editor of the Monson Weekly Slate in 1885: “He would use cheap Bangor newsprint to boost his town’s fortunes and his own” (87). Print technology was one of many technologies that brought urban and rural culture together. Sprague drew other towns into Monson’s orbit. Late nineteenth century rural readers and writers are just being recognized by historians for their historical significance (88–9). “Slate also championed understandings of progress and locality that embraced outside influences. . . . Sprague did not wish to build a wall around Monson” (92, 95).

Witmer tells the fascinating story of the bird’s-eye panoramic images of Maine towns drawn by artist George E. Norris. The lithographic prints of these drawings radically changed the way people saw their towns, as they depicted industry in bucolic settings, thus enhancing the town’s image (100–103). Monson Academy was a center of print culture with its reading room offering some of the best national periodicals. Its annual magazine The Pharetra was a place for local scholars to sharpen their skills and be noticed (105). A new library was opened in 1909 as the call to higher education seemed to also be calling the younger generation away from Monson (110, 112). Witmer concludes this chapter by noting that “In the decades following the Civil War, urban printers, artists, and writers included Monson in their efforts to monetize the drive of rural people to distinguish themselves and their place” (115).

Chapter 4, “Over Here and Over There,” demonstrates the changes caused by mobility as Monson citizens leave and other people move in. It also explores Monson’s participation in World War I. Immigration took place, not only in urban places, but also in rural small towns like Monson, which received a large number of Swedish immigrants in the 1880s (117). They established themselves first and most importantly by building a church and by 1889 were able to call a regular minister (121). Along with Welsh and Canadian immigrants, this influx opened Monson to global influences, but they determined to participate fully in American life (126).

Witmer elaborates at length on the Swedish artist Carl Sprinchorn (1887–1971). He studied under Robert Henri, a well-known artist from New York City (127). Becoming friends with Monson resident Ether Johnson brought him frequently to Monson. He applied the dynamic techniques he had learned in the city to rural life, especially the logging community, in which he was forced for a time to work out of financial necessity. He captures the loggers in motion, based on the Renaissance technique of contrapposto, in which the weight of the subject is centered on one leg, giving the artwork dynamic movement (140). His art was a unique melding of realism and abstraction:

Sprinchorn was also imposing his own distinctive vision of his subject matter rather than simply documenting reality. . . . The artist was hunting dreams. . . . the painter’s achievement in Monson was to elevate and intensify reality rather than abstract it. (142, 144–45)

World War I figured prominently in Monson life, as dozens of Monson’s young men ended up on the battle fields of Europe (129). Witmer’s storytelling skill shines in his portrait of the lives of two Monson men—Elmer Lindie and Frank Flint (130). They barely knew one another in Monson prior to their enlistment in the army, but they returned as friends bonded for life. The experience of war changed their relationship, not only of each other, but to their town (134). Witmer concludes this chapter: “Immigration and other forms of movement into and out of town never altered the fact that Monson was a tiny place, but they changed the texture of local life, ensuring that Monson’s experience and history stretched far beyond its borders” (153).

Chapter 5, “What Is Right around Me,” looks at changes effected by technology as Monson residents used it to their advantage. Eventually, however, their industries succumbed to globalization. In the summer of 1909 electricity arrived in Monson (154). Meanwhile immigration stopped and tourism ground to a halt (155). The slate industry peaked between 1897 and 1914 (157). The invention of asphalt shingles led to Monson’s slate mines inventing new uses for slate, such as sinks. The advent of the automobile was another strong influence on Monson, although horses were not immediately replaced by them. By 1922 there were eighty-six cars in town (162–63). “As they remade their place with electricity and automobiles, and saved the local economy by adjusting nimbly to changes in the slate industry and to nationwide economic collapse, Monson people also worked to reach urban markets with local products” (164). One of those was spruce gum, produced by Harry Davis (164–65). Then there was the growing popularity of hiking the Appalachian Trail, which went right through Monson. Providing boarding and supplies for hikers became a great source of income and mutual influence (167–74, 184). The Monson Maine Slate Company closed its doors in 1943. Moosehead Woodcrafters renovated and moved into their building, making wooden boxes and furniture (175).

Acclaimed painter Alan Bray had deep roots in Monson (177). Witmer’s concentration on artists in his Monson story portends the present development in the town’s history (177–80; 185–86). Monson Academy closed in 1969 (181). Moosehead Woodcrafters closed its doors in 2007 (188). But all was not lost as we see in the unexpected ending in the Afterword.

The influence that the electronic environment has on modern life tends to undermine a sense of place, a theme that could have been more prominent, especially in Chapter 5. Joshua Meyerowitz provides a profound exploration of this topic in No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior (Oxford, 1985). I met him in the mid 1990s while I was working on my book on preaching and electronic media (The Word Is Worth a Thousand Pictures: Preaching in the Electronic Age, 2001). His inscription in his book captures my sentiment concisely: “To Greg Reynolds, who maintains a strong sense of place in the face of the temptations of electronic displacements.”

The Afterword, “Silicon Valley and Small-Town Maine,” brings the story up to Monson’s bicentennial anniversary with a surprise ending: a Silicon Valley philanthropist, Betty Noyce, comes to the rescue helping turn Monson into an arts community. She was the ex-wife of Robert Noyce, the co-inventor of the microchip and co-founder of Intel. She and native Mainer Owen Wells formed the Libra Foundation, seeking ways to spark economic recovery in Piscataquis County, founding Monson Arts in Monson as part of “creative placemaking,” putting feet on Noyce’s “catalytic philanthropy” (191–94). The irony of this ending is not lost on me. The very Silicon Valley industry that is causing electronic displacement and undermining a sense of place also brings wealth that, in the right hands, turned out to be an important part of a solution for Monson’s future. The globalization that helped ruin the furniture business enabled Monson to begin a whole new chapter in its history.

To the main threads of this tapestry of a rural Maine town Witmer attached numerous details of local color. Whether you are interested in this example of historiography that blends the local with the big picture or the details of a century’s changes experienced by a small northern New England rural town, this will prove to be a rich and entrancing read. Witmer has done extensive research in local archives (as the 42 pages of end notes attest), enabling him to tell numerous fascinating stories in order to tell the big story:

Exploring the history of this obscure rural place (and others like it) offers an opportunity to view major changes from novel perspectives, accounting more fully for the agency of rural people and working across spatial scales that are too often studied separately. Expansive local history may also promote dialogue between academic history and the ongoing rural tradition of locally authored local history by advancing a richer account of locality, one that conceives of the local in relationship to rather than isolation from larger scales of activity and identification. . . . As Monson marks its bicentennial in 2022, townspeople find themselves deciding once again how to weave the outside world into their place. (197–98)

It is a great review. Can you please send me the footnotes?

Ian Johnstone

ianjohnstone003@gmail.com

Comments are closed.