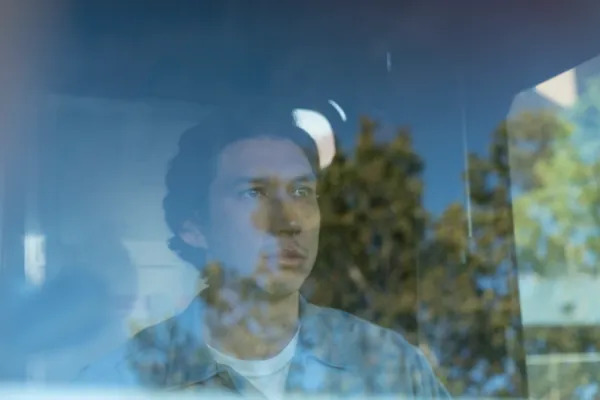

Lexington, VA. I am late in writing about the film Paterson. In 2016 critics and audiences greeted it with delight. The buzz was especially strong in literary circles since the film, written and directed by Jim Jarmusch, focuses on a poetry-writing public transit driver (played by Adam Driver) in Paterson, New Jersey, a city famously associated with two other poets: William Carlos Williams, who practiced medicine there, and Allen Ginsberg, who spent his youth in Paterson. The bus driver has cleared out a writing space on his basement workbench. A pair of tire chains and a photo of Williams hang on the wall beside the bench, further suggesting the two sides of his life.

Williams’s sharp doctor-poet eyes seem to scrutinize the lines being written on the bench. Williams is the presiding spirit of the place, its poetry, and Jarmusch’s film. Williams’s own epic about the New Jersey city provides the thematic and imagistic architecture for the film. Williams’s Paterson is one of the poetry volumes stacked prominently on the writing workbench. At one point, the driver’s wife Laura (played by Golshifteh Farahani), asks him to read Williams’s famous apology note while they stand, fittingly, in their small kitchen. Despite these explicit nods, though, I found myself thinking throughout the film about another famous Williams poem:

so much depends upon a red wheel barrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens

The poem frustrated, maybe even infuriated, me when I first encountered it in ninth grade. What depends on this soaked wheelbarrow surrounded by fowl? Like most middle school students, I tried to read the poem literally. Is this the surviving remnant of the farmer’s decimated flock? Had a long-anticipated rain broken a drought and saved the parched farm? Perhaps. Growing up on a small farm, I knew something about such stark realities, about holding your breath as you wait to see if the calf will be born alive or if that distant lazy thunder will finally yield rain. The poem does evoke basic farming necessities: tools, stock, water.

But as a middle school student, I had no patience for the poem’s ambiguity and suggestiveness. I had no awareness of what, in college, I came to see as one of its main implications: much depends on how we see such a tableau, on seeing it poetically, on seeing the seemingly banal barnyard scene as singular: this wheelbarrow, beside these chickens, evoked and illuminated by these words. It is a poem that helps us see the aesthetic richness in the mundane. Poets can cultivate such poetic seeing in both themselves and their readers. Paul Mariani is Williams’s biographer and a great poet in his own right, one with his own ties to Paterson, New Jersey, where his mother was raised. Mariani notes how a poem like “The Red Wheelbarrow” helps us see “the thing reimagined and reassembled, refreshed and rinsed and renewed, glazed now with a finish of rainwater, upon which of course so much depended.” In his poetry, Williams invites us “to see the thing itself,” to “behold the world itself right there before one, here, now, in Paterson.” Wendell Berry insists that such seeing is not just the luxury of an aesthete. In his book on Williams’s poetry, Berry asks, “But don’t we know that difficult and painful lives have been made livable by just such comely small visions as this poem gives us, and by somebody’s ability to say such graceful things about them?”

This is why the film Paterson had me thinking about “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Its urban scenes are far removed from that poem’s rural one. But the poems the bus driver writes and the life out of which he writes them are built upon such seeing. He sees the people and places of his city as if much depended on it. Like Williams before him, he makes his own rounds through Paterson, albeit as bus driver rather than doctor. Paterson writes in the driver’s seat of the bus each morning in the minutes before his launch time. He takes his midday meal on a park bench next to the city’s waterfall, scribbling in his notebook in between bites of food carried in his old-fashioned metal lunchbox. And all day, while driving the bus, he sees and hears his world and works on lines in his head. The bus driver’s parents (photographs of whom presumably stand on his nightstand next to a photo of the driver himself as a young Marine) named him after the city. He is Paterson, both on his birth certificate—we learn in a bar conversation that it isn’t a nickname—and in how he receives the city and then transfigures it on the page. “A man is indeed a city,” writes Williams in a line that could serve as the film’s epigraph.

Paterson’s job seems to wear on him at times, though he has genuine affection and goodwill for his passengers and fellow citizens. His contemplative, poetic seeing keeps his daily job from becoming a daily grind. The film emphasizes circular repetitions. The camera lingers on the cheerios in a breakfast bowl, on the bus’s giant steering wheel, on a turning washing machine in a laundromat, on the face of Paterson’s wristwatch. Paterson spends all day circling his bus route. The broader circular repetitions of workday and workweek structure the film. Paterson’s contemplative awareness, however, elevates his daily patterns into significant repetitions, each with its unique variations, its easily missed differences. Commenting on the pattern that Laura has painted on their dining room curtains, Paterson says, “I like how all the circles are different.” Paterson notices that the circles are different, and not just the ones on the curtains. He does not allow his life to slip into boring routine. Or if there is boredom here, it is the kind that the philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls “profound boredom,” where restlessness gives way to deep awareness that does not rush things along, that greets whatever and whomever comes up.

Some would undoubtedly see the driver-poet Paterson as nostalgic, as living in the past. Paterson’s ears perk up when he hears passengers on the bus talking about events and residents from the city’s history. Each evening, while walking his wife’s dog Marvin—the one inhabitant of the city for whom Paterson has ill-will—he stops in at a bar. He is friends with the bartender/owner Doc (played by Barry Shabaka Henley). One of their favorite topics of conversation is the city “wall of fame,” to which Doc continually adds photographs and stories snipped out of old newspapers. When a pool player asks Doc whether he is going to get a television so they can watch sports, he responds, “Hell no!” Like Paterson, Doc attends to the world and its inhabitants, though his favored practice for building attention is chess rather than poetry.

Yet even Doc is amazed that Paterson does not have a cell phone. As I said, many will undoubtedly see Paterson as a gentle crank, living an anachronistic existence. But that misses the main point of the film. The point is not that Paterson is stuck in the past but that a cell phone would keep him from being present (though, when his bus breaks down, we also see that a cell phone can come in handy). Paterson somewhat enigmatically tells Doc that a cell phone would be a “leash,” perhaps pointing out how it would pull away his attention. The film reminds us of the kind of seeing that we lose when we bury ourselves in our screens. It reminds us of the resplendent, compelling world that we routinely ignore but that is always available to us. The film encourages us to read and write poetry, but at the most basic level it champions this poetic seeing, conveyed not only in the lines of Paterson’s latest poem but also in lingering camera shots: morning light cutting across an old brick building, bubbles in a mug of beer. Likewise, Paterson’s interest in local history is not a matter of living in the past, or of antiquarian trivia, but of his sense of the unfolding, ongoing history of the city, of both its strengths and ongoing struggles. Perhaps it is significant, in this regard, that the passengers who discuss this past are not old-timers but kids.

Perhaps there is more nostalgia in the depiction of a contemporary city—even Paterson—where poetry is still so vital, where it is not just appreciated and practiced in classrooms and on college campuses but by a bus driver and a surprising number of people encountered over the course of one week. The film presents three encounters with other poets. The first poet (played by Method Man) is working on a rap in an otherwise empty laundromat. Paterson overhears him while walking Marvin. The first line is “They call me Paul Laurence Dunbar. I wear the mask.” This alludes to Dunbar’s famous poem about racism and the masking it necessitates. The poem underlines the differences in identity and experience between this poet and Paterson. They connect over the shared love of poetry, though, the creative spark that flashes in the everyday. Paterson compliments his work-in-progress and jokingly asks, “This your laboratory?” The man responds, “Wherever it hits me is where it’s going to be”—a sentiment and a practice that applies to Paterson’s art as well.

Later in the film, Paterson sits with a young girl (played by Sterling Jerins) in a somewhat seedy alleyway, so that she will not be alone while waiting for her mother and sister. The girl is writing her own poems in a notebook, and she shares one—a lovely one—with Paterson. When she leaves to join her family, she says, “Awesome—a bus driver that likes Emily Dickinson.” Awesome indeed. On the rest of his walk home, Paterson tries to memorize her poem. He later shares it with Laura.

Finally, at the end of the film—and here a spoiler warning is in order—after Marvin has chewed up Paterson’s own notebook full of poems and sent him into despair, a visiting poet from Japan (played by Masatoshi Nagase) joins him on the bench beside the city’s Great Falls. They talk about poetry and William Carlos Williams, of course. Paterson does not say that he is a poet, but the man seems to intuit it. He proclaims it “very poetic” that Paterson is a bus driver in this city and gives him a blank notebook.

A twenty-first-century city where poetry seems more prominent than smartphones may seem whimsical, to say the least. The last encounter borders on the miraculous, especially in that the visiting poet seems to sense what has befallen the daunted driver-poet. Yet poetry was a vital part of everyday American life deep into the twentieth century. The film gives its nods to a past when poetry was in the newspaper and on the shelves of many homes, to a past when blue-collar workers with metal lunchboxes might well read, or write, a poem. But the film also invites us to see poetry as a living tradition, one that is perhaps not as insular and university-bound as it seems. It persists in popular music. It still captures the imagination of schoolchildren. It still offers the possibility of unexpected common ground when two poetry-loving strangers meet. And it still has its practitioners and readers off-campus. But perhaps I am just the ideal nostalgic viewer for a nostalgic film. (I once wrote my own poem about a long-haul trucker who loves poetry.)

William Carlos Williams may be our driver-poet’s tutelary spirit and poetic grandfather, but his muse is Laura. Her name evokes Petrarch’s Laura, and the film eventually makes this allusion explicit if you miss it at first. She tapes pictures of herself in Paterson’s lunchbox each day. He meditates on them as well as the waterfalls as he writes in his notebook. One day she also includes a Dante postcard with a small rose taped to it. Again, the muse is evoked. She is Laura and Beatrice. Perhaps the evocation of the latter suggests that she has led Paterson out of a dark place. We do not know for sure, but it is plausible. Melancholy laces through his gentle beneficence. One can imagine his introversion and awkwardness sliding into reclusion. The timing of Paterson’s Marine stint would line up with some serious deployments.

At the very least, Laura and Paterson are clearly in love. Several of the poems he works on throughout the film are love poems. She draws him out of himself and continually, genuinely, encourages him in his poetic endeavors. And she is an artist herself. While Paterson’s is an observational art, however, hers is a more experimental, more spontaneous one. They balance each other that way. Perhaps they even suggest two poles of art itself. Laura loves to paint intricate patterns of black and white—on window hangings and shower curtains, on her clothes, on cupcakes, on the oranges in Paterson’s lunchbox. In her own way, she takes a life that could become monochromatic and turns it into polka dots and harlequin. When Laura makes $286 selling her cupcakes at a farmer’s market, she fittingly takes Paterson to see a zany black-and-white horror movie at a retro theater.

There is nonetheless a marked difference between this Laura and Petrarch’s Laura or Dante’s Beatrice. She is not an idealized, distant love. She is a muse within a daily relationship. We see Laura and Paterson encouraging each other’s artistic pursuits, sharing jokes and tender moments, and bearing with each other’s foibles. The film is somewhat rare in showing the repetitions of a happy relationship. Both early and late in the film, we see Paterson and Laura facing each other in bed, asleep, with their arms and feet meeting in such a way as to form a loose heart shape.

The philosopher Gabriel Marcel at times contrasted constancy with what he called “creative fidelity.” The former is just sticking with something or someone. The latter is responsively cultivating a relationship. Creative fidelity is attuned to, and draws out, the richness in people and things. It calls for awareness and attentive seeing. In the end, Paterson is a film about such creative fidelity to a place and its people. It is about creative fidelity within a relationship. It is a film about the poetry that emerges from such fidelity, from the appreciative and attentive seeing that it requires and sustains.

Image Credit: Photo of Great Falls, Paterson NJ by Tony Fischer

thanks I’ll rent the movie; ps don’t forget cowboy poetry is going storng.

Comments are closed.