Donemana, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. The deeper I get into middle-age, and the more my time is swallowed up by the just demands of family and parish ministry, the more gruesome my crimes against literature become. Here is an egregious one: until recently, it had been far too long—probably years—since I’d read a narrative poem. But recently, I read Marly Youmans’ Seren of the Wildwood.

The poem came providentially, an unlooked-for eruption of goodness into my stacks of commentaries and sermon notes. Seren of the Wildwood is a thin place, a nexus between the waking world and that hazily surreal, maddeningly concrete, constantly shifting landscape of the dream world. Youmans’ gift for creating primordial archetypal images that stir the gut and fascinate the eye of the mind places her among the best of the poets. If you’re a connoisseur, even a lapsed or dilatory one, of narrative poetry, buy Seren of the Wildwood and read it today.

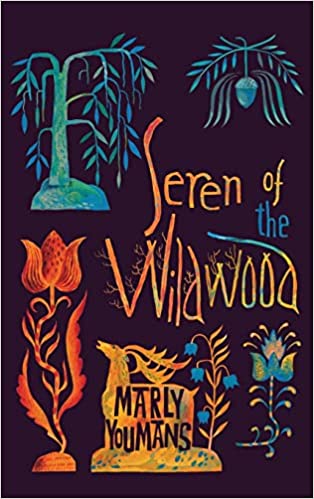

To begin with, the book, a stereotypical slim volume of poetry, is gorgeous. The work of illustrator Clive Hicks-Jenkins is fantastic—in the etymological and informal senses alike—in how he translates Youmans’ copious and varied imagination into a visual lexicon. The images interspersed through the text recall (inter alia) the doodles and illuminations of Irish monks, Greco-Roman sculptures, William Blake’s illustrations, and Van Gogh’s still-life paintings. Perfect harmony exists between text and image, even on the occasions when the image doesn’t obviously function as an illustration of some particular concept from the poem.

There is also a nice congruence between the poem and the page: each stanza fits perfectly onto a single 9” x 6” page. It’s almost as if Youmans planned her formalized stanza with the volume in mind. Most spreads have two stanzas; the rest include an image on one side plus a stanza and doodle on the other. The pages feel neither too empty nor too crowded—which is good, because by golly the poem itself is crowded, but I’ll get there later.

Seren of the Wildwood begins not with a prologue, but with a prolegomenon. The difference is significant, for a prolegomenon is not merely informative, but schematic or methodical. It provides the interpretive key for what follows. My policy as a reviewer is to avoid spoilers at all costs, which (thankfully) in this case relieves me of the burden of explaining how to interpret Seren of the Wildwood—my children often ask me about my dreams, and however powerfully I experienced them, I find it difficult to explicate their deeper meanings. Nevertheless, the prolegomenon is deeply significant both in its proleptic function (which provokes the reader’s sense of dread and hope for redemption) and in the way it raises questions that will not be answered for quite some time, if at all.

Youmans tackles two big tasks in the prolegomenon. First, she introduces the primordially mystic wildwood, the wholly ambivalent landscape that dominates the poem. In Youmans’ words, “The wildwood is a tough / Terrain, yet beauty springs / Like diamonds from the rough.” The rhyme of tough/rough gropes towards the ferocity of the place; the image of the emergent diamonds testifies to the painful possibility of redemption. The prolegomenon also complicates any interpretation of the poem with its maddeningly suggestive title, “Prolegomenon, in the voice of Wren.” Who speaks “in the voice of Wren” – the poet, Wren herself, or some other entity? I reckon answering that question (even with the likely answer of “Who knows?”) is an obvious starting place for any sort of critical reading of Seren of the Wildwood.

The prolegomenon is identical in form to the other 61 stanzas: 21 lines of unrhymed iambic pentameter followed by a bob-and-wheel metrically similar to that used in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: a bob (one-foot line) rhymed into the wheel (four three-foot lines). That makes a total of 62 stanzas of 26 lines, and while my inner numerologist and medievalist are screaming about palindromic or chiastic significance, the still small voice of my inner editor exhorts me to move on. Perhaps some arcane consideration for mystic numbers impelled Youmans to end the poem where she did; I thought that it ended suddenly, and more like a motorway ending abruptly in the middle of a city than a trail coming out of a forest and halting on the edge of some precipice affording magnificent panoramic vistas of the illimitable ocean. A few more stanzas to round things off would, in my estimation, make the thing feel more like a conclusion than an ending.

That said, I suspect Youmans knew exactly what she was doing by ending Seren of the Wildwood as hastily as I felt she did. Although neatly assigning a genre to the poem may prove impossible—is it a fairy tale? a lay? a Greekish tragedy?—it certainly has strong affinities to medieval dream visions such as The Pearl or Confessio Amantis. But of course, deeply steeped in medieval poetry as Youmans is, she has recourse to a rich vein of sophisticated techniques for narrating the inner workings of the human soul. Seren of the Wildwood is nothing if not dreamlike—and not in a comforting way. The prolegomenon strikes a note of foreboding which swells perceptibly in the first stanza and dominates large portions of the poem. Reading the poem is like a feverish nightmare, in which some awful and awfully inarticulable sense of doom hangs over the reader as the scene shifts whimsically and characters flit momentarily across the periphery of vision while leaving a sharp impression, where everything seems startlingly new yet possessed of a familiarity that is simultaneously welcome and terrifying, where it feels like your feet are chained or weighted as you try to flee from whatever fell beast is pursuing you through the weirdest and most inhospitable terrain—and that terrain itself seems to be indistinguishable from all the nightmarish terror—when all of a sudden, striking through the disorientating web of dream, comes unexpectedly the blessed gift of waking to the birdsong of a bright morning of the incipient spring. Perhaps the sudden ending is Youmans’ mimesis of waking to the fragility of renewed hope.

A central component of Seren of the Wildwood’s mythical dreamworld is the ubiquity of primal archetypes. Rash words; woodside cottages; prophecies; unheeded warnings; god-kings; fertility religions; hermits; rites of purification by water; preternatural births; mountaintop gardens; dreams and visions—these are the threads with which Youmans weaves, and of which no lover of narrative poetry grows weary. What is particularly impressive about Youmans’ weaving is her ability to use such venerable archetypes freshly. Yes, I’ve met them all before, and given time I could tell you where. But meeting them in Seren of the Wildwood reminds me of the time a man I’d known for years shaved his moustache and became unrecognizable for a few shocking minutes. The effect was initially disruptive—for several seconds I knew I was failing to recognize a familiar face, a face I’d seen recently in different guise. Recognition came soon, but it was not particularly comforting to see the pale wide acreage of his upper lip. Something essential, I felt, had changed in the man’s appearance. The same with the landmarks and inhabitants of Youmans’ Wildwood; they seem hauntingly familiar yet disconcertingly strange. Her power simultaneously to defamiliarize and reenchant is enviable and deliciously enjoyable.

Even more so is Youmans’ willingness to venture into dark places—into the black heart of the Wildwood, no less—and return carrying a light. Terrible things happen to poor Seren, who becomes a sort of Job or Griselda (though without a YHWH and Satan or a Walter directing her testing in the background), yet she is neither bereft of friends nor devoid of healing. Youmans is neither sentimental nor nihilistic about suffering, but rather glimpses something of its obdurate inevitability and its redemptive capacities. The Wildwood is not just a dreamscape, it is a place where at some point in life every person wanders, torn and hungry, yearning for nothing more than to encounter the spreading horizon where the forest ends.

The poem is not perfect; only rarely does a poem of any length attain perfection, and I doubt a single poem anywhere near the length of Seren of the Wildwood avoids the odd misstep. Youmans’ vocabulary is rich and her syntax wonderfully fluid, but my feeling is that she sometimes goes too far in piling up synonyms. For example: “the shape was such / A wraith, phantasm, apparition” (pg. 42); “His fairy-story growth ferocious, fierce / Outlandish and preposterous […] It seemed satanic, manic, half insane” (pg. 45); “All the ground seemed jocund, jaunty, gladsome” (pg. 52). Such variation might delight some readers; it reminds me of P.G. Woodhouse dropping thesaurus entries into his prose for comedic effect, which rather blunts whatever edge Youmans hoped to wield. Also, a few phrases were unquestionably clunky. But Youmans’ shortcomings are few and relatively minor. After all, even Homer nods.

Distant are the days when writing excellent poems assured a poet of a place in the canon, or fame, or even public notice equivalent to the exploits of a D3 college football team. Such are our times—which is surely unfair on Youmans, who at the least deserves to be known as the creator of the Seren stanza. My first encounter with Seren of the Wildwood brought to mind dozens of my favourite poems, poems that over the millennia people have taken the trouble to read, copy, annotate, memorise, and perform. Seren of the Wildwood reminded me of them by way of family resemblance; the poem is at home among the poems that last. It is a good poem. A very good poem.

Here is what Seren of the Wildwood has done for me: it’s rekindled my love of narrative poetry. Once I have read several of my old favourites, I’ll read it again, and then I’ll move on to the rest of Youmans’ work. In the meantime, dear reader, put your order into Wiseblood Books and get to reading the instant your copy of Seren of the Wildwood arrives. If your literary tastes are vaguely similar to mine, you’ll enjoy it thoroughly.

Image Credit: Peter Paul Rubens, “A Forest at Dawn with a Deer Hunt” (1635)