Ithaca, NY. Over the years, I’ve gotten NCAA men’s basketball tournament brackets down to a science. I used to run my own blind trials, using a website that removed team names and allowed me to choose my champion based on statistics instead of cognitive biases.

And every year, I’d put my head in my hands as some midwestern school bricked the three-pointers I was sure it would make and once again dashed my hopes of winning my bracket pool. The pain worsened when my friends moved our competition to ESPN’s bracket platform where I could see precisely how my selections stacked up against the rest of the world. For all my striving year after year, I was mediocre. It was too much for one college basketball fan to bear; this year, I decided to ignore the bracket and enjoy March Madness on its own merits.

Choosing not to predict game outcomes contradicts the direction of modern American sports where betting is becoming a defining part of the fan experience—but I suspected I could find joy by watching March Madness without caring how the games ended.

NCAA men’s basketball brackets have become a national obsession in the past couple decades. 150,000 basketball fans joined bracket pools in 2006. The four biggest online bracket platforms drew over 20 million entries in 2023 (some of these were certainly duplicates, but the growth is notable nonetheless).

No one knows precisely why brackets took off. Friendly workplace and church bracket contests certainly play a part. There’s also something unmistakably fun about choosing a winner among a big group of competitors—hence the Denver taco bracket and Mammal March Madness. But money plays a part, too—since Warren Buffett pledged $1 billion to anyone with a perfect bracket, platforms have taken to offering cash prizes for the most successful brackets. My friends and I would often pitch in a few bucks to make our bracket pool more interesting.

Money will drive the March Madness bracket phenomenon forward. Sports betting has grown by magnitudes in the last five years, and gambling companies now sanctioned by 36 states are using the excitement of March Madness to expand their orbit.

“From a recruitment perspective, March Madness is one of our tentpoles,” the CEO of BetMGM told Fortune. “March Madness bettors have shown themselves to be high-quality bettors.”

Many of these high-quality bettors are my age: College students are a lucrative market for sports betting, and companies are throwing money at us. When sports betting was legalized in New York, one of my friends figured out a risk-free method to take promotional “free” bets and reliably double an investment of up to $3,000. In the past two years, my Instagram feed has been flooded with sports betting propaganda showing videos of fans screaming in delight after hitting on a big bet.

I was at a friend’s house during the legalized-betting craze of 2021, watching one of his housemates place basketball parlays. “You’ll only lose money,” my friend chided the bettor.

“I know, I’ll only lose money,” the housemate muttered to himself, continuing to place bets on his phone as the actual basketball game went unwatched on the TV in front of him.

Caesar’s Sportsbook, one of the flagship online sports betting platforms, has built a brand around ostentatious advertising based on the brand’s slogan: “We can all be Caesars.” The phrase is a telling contradiction in terms. Nearly everyone to ever exist cannot, in fact, be Caesar. The house always wins at a casino. My peers are being encouraged—sometimes by their own universities—to throw money at an impossible dream. No one will ever win Buffett’s billion, but it won’t be for our lack of trying.

Also underlying the March Madness bracket craze is a sense that watching sports is only enjoyable if the fan has a stake in the outcome. The Fan-Controlled Football league, which is optimized for streaming and allows fans to vote on plays using their phones, is entering its third season and has former NFL talent aboard. Immediately after entering the Washington Nationals’ stadium, fans are greeted by a large indoor casino where they can place bets before or during the ballgame. The new vibe is distilled by sports betting platform DraftKings, whose slogan reads “Life’s more fun with skin in the game.”

But sports can be more beautiful without financial skin in the game. In a 2011 episode of Radiolab, the pop economist Stephen Dubner is asked why he cares about sports.

Dubner responds, “It’s war where nobody dies. It’s a proxy for all our emotions and desires and hopes. I mean, heck, what’s not to like about sports?”

March Madness is a tournament where young men, the vast majority of whom will soon move on to careers in sleepy European basketball leagues or as insurance salesmen, have three weeks to immortalize themselves in campus lore. Teams need to be perfect; if you lose, you go home.

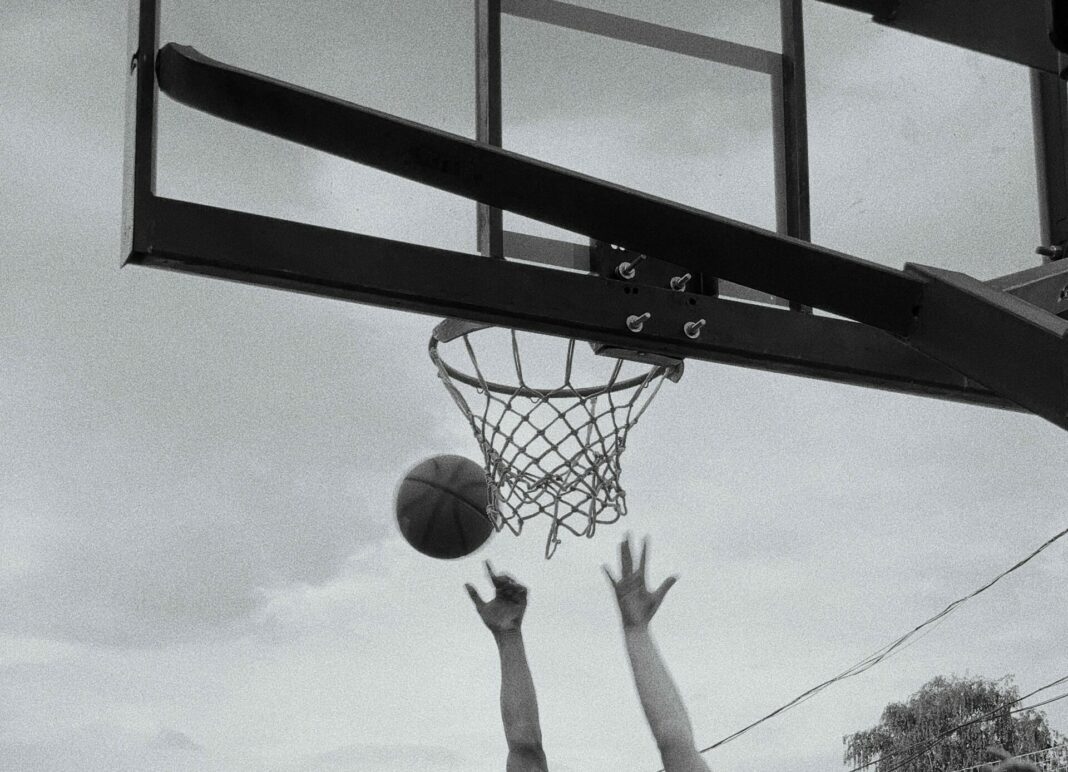

Unscriptable things happen. Fairleigh-Dickinson University (I’ll give you five bucks if you can tell me where that is) toppled the mighty Purdue Boilermakers and their consensus All-American forward. Transcendent sports moments are a guarantee: Recalling Kris Jenkins’ buzzer-beating shot to win the title for Villanova in 2016 elicits a kind of joy in myself I can’t fully explain. Why do we need brackets? March Madness is quite interesting enough as it is—and if you don’t have a vested interest in the outcome of every single game, you can watch this deeply human tournament unfold without disappointment lurking around every corner.

Maybe we could love sports differently outside of March, too. G.K. Chesterton, a self-professed terrible croquet player, argued that truly loving a game takes loving it for supernatural reasons, with a passion that defies incentives or reason. A winning croquet player loves glory; the loser loves croquet.

“I love the mere swing of the mallets, and the click of the balls is music. The four colours are to me sacramental and symbolic, like the red of martyrdom, or the white of Easter Day,” Chesterton wrote.

I’ve been thinking about Chesterton’s croquet essay a lot during March Madness. Watching games without the specter of a ruined bracket to kill my vibe, I find myself drawn more to basketball itself than to who wins and loses. Well-played basketball is a fluid life-sized chess game where David outsmarts Goliath fairly often.

I’ve rediscovered that a game can take my breath away. When Furman’s J.P. Pegues drilled a three-pointer to seal the Paladins’ upset win over UVA, my bracket wasn’t busted. I didn’t make any money, either. I cried out in joy, wondering how I got so lucky to witness something so enchanted.