Not soon, as late as the approach of my ninetieth year,

I felt a door opening in me and I entered

the clarity of early morning.

One after another my former lives were departing,

like ships, together with their sorrow.

-- Czeslaw Milosz, from "Late Ripeness"

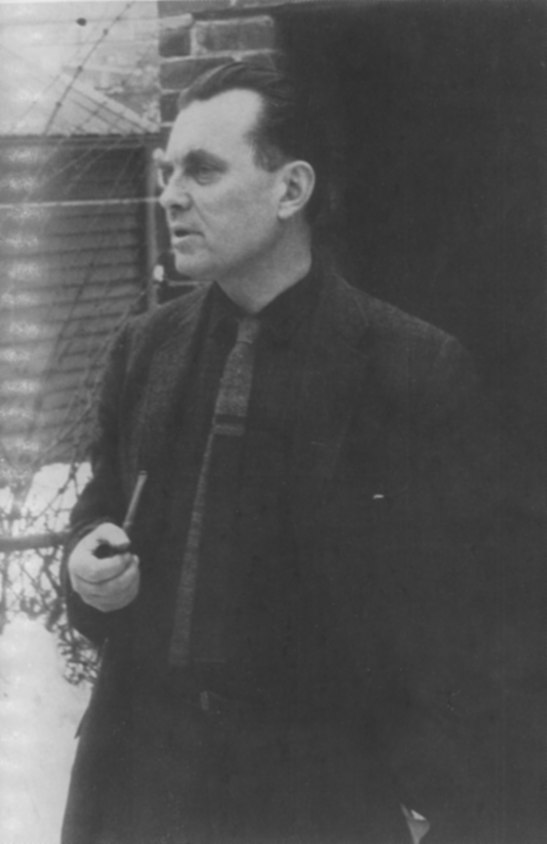

Baltimore, MD. In my early thirties, I discovered the poetry and prose of Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz. I don’t remember the title of the first poem I read of his, but it was posted on a bulletin board in the hallway of the local community college. I began reading his poetry and prose, as well as Andrzej Franaszek’s Milosz: A Biography. I found in Milosz a kindred exiled soul. He has since become a sort of patron saint—albeit a strange one—to me.

I spent the bookends of my childhood in India—born in the foothills of the Himalayas, I later spent my last two years of high school in New Delhi. In between were stays in Pakistan, Jordan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the U.S., and Hong Kong. Those who don’t get it ask me, “Where are you from?” Those who do get it ask, “Where is home for you?”

Any answer I give leaves me feeling fake and homeless—exiled. I could never claim to be “from” even the place that felt most like home, India.

Exile exacts a toll on the mind, body, and spirit. To carry always the weight of not belonging, of not being “native,” of not being able to return home, or not to be able to call anywhere on this earth home—it is a low burn, an irritant.

You learn to adapt by observing, by making a million small decisions about when to try to blend in and when to risk standing out. You chameleon yourself to each situation, each mini culture in which you find yourself. Sometimes you lose—your own self, the chance to embrace your difference, the opportunity to see from a new perspective.

Milosz lived most of his life—which spanned most of the twentieth century—in some form of exile, in mind as well as in body. That thread of exile runs through all his works. As his fellow intellectuals in Poland were choosing ideological sides—and although he leaned left—Milosz found himself uncomfortably alone in discerning where both Communism and Polish Nationalism were leading. One article by Adam Kirsch details that

By the end of the thirties, Milosz’s intellectual position was becoming intolerable. He was opposed to everything the Communists opposed, yet he suspected that a Communist takeover would be disastrous. At the same time, anyone could see that Poland’s future held war or revolution, or both. Contemplating the fate of his country, he wrote, years later, “I had a kind of horror, some basic dread.”

After a strong infatuation with Communist ideas as a young adult, he realized what the ideology meant for art, literature, truth, and humanity: “Nazism threatened the body, whereas Communism demanded the surrender of the soul. For a poet like Milosz, the latter seemed like the greater sacrifice.”

Despite numerous brushes with death, Milosz survived the Nazi occupation of Warsaw and the subsequent Stalinist-puppet Polish regime. Serving in the U.S. as a cultural attaché for the post-war Polish government, he came under increasing scrutiny back home for his “unorthodox” views. After being recalled to Poland and having his passport confiscated, he was fortunate when someone intervened on his behalf, convincing the government he should be allowed to represent Poland in Paris. Within days of his arrival in Paris in January 1951, he defected, requesting asylum.

Milosz knew the power of ideas and could intuit where they would lead. He wrote, “artists’ antennae pick up every wave; and they suffered, surprised that they did so.” He suffered from his premonitions, from his lived reality of war, siege, political danger, and exile—and from his memories and survivor’s guilt.

I know very little of those realities. Why, then, this connection I feel with Milosz? Is it intemperate pride to suggest that my antennae, too, sense what is coming and tremble—here, at the sputtering end of the Enlightenment project?

Milosz’s early work (pre-WWII), which he labeled catastrophism, included intuitions and forebodings of the horrors to come. He knew something fundamental was changing in how humans understood themselves and their societies. Milosz wrote of his early awareness that by the early twentieth century, “all the human concepts of man and of society disintegrated and a new dimension unveiled itself.” All around him, fellow intellectuals were worshipping History—that is, power and “progress”—but Milosz, according to Kirsch, worshiped truth, “which is what allow[ed] him to save his soul.” He was out of step with his times, which left him in intellectual limbo. He could never get away from his clarity of vision—his trembling at the consequences of the prevailing ideologies of his time. Though he sometimes doubted his own interpretations—and even if his own nature bucked against it sometimes—he was true to the way he saw reality and the world.

By this he gives me courage. He reminds me, as he anchored himself, not to write for praise, distinction, or fame, but to be faithful to reality and to one’s vision, which is a gift from God. “If you are going after enchanting people,” he once told an interviewer, “you may be a little inclined to make compromises, to be a follower of various fads of a given time.” His dictum to himself “not to enchant” helped him stay true to his conscience as he wrote, using his words “as weapons or as instruments against chaos and nothingness.”

Milosz was haunted by a strong sense of calling—he understood his vocation as a poet to be akin to that of a prophet or scribe (though at darker moments he also described it as a type of demonic possession). Even if the idea of poetry as a vocation was being lost or ridiculed, he knew it was a true and honorable thing. He sensed things to come. He was sometimes called a “sensuous mystic.” I wonder: is that the title one bears in this era if one writes seriously about ultimate—but neglected—questions? Is this one more way to experience a sense of exile in the world today? I, myself, feel this sometimes.

I think often on this question, as “sensuous mystic” carries a connotation that such a writer’s themes or questions might be dismissed as irrelevant in our times. But throughout his poetic career, and increasingly in his later years, Milosz challenged those who considered ultimate questions of religion, metaphysics, and the meaning of human life to be taboo in literature and art.

I lived at a time when a huge change in the contents of the human imagination was occurring. In my lifetime Heaven and Hell disappeared, the belief in life after death was considerably weakened. How could I not think of this? And is it not surprising that my preoccupation was a rare case?

At the same time, Milosz realized that an “ethics based on scientific principles is an impossibility”—that science is impotent to answer fundamental human questions of meaning and purpose, of telos. He believed poetry ought to deal with those essential questions. He encourages me not to cede the ground of poetry to those who would deny its imperative to speak to issues of human life, faith, and the order and meaning of the cosmos.

Yet this stance has costs. Milosz longed for fame but gave up the chance for it again and again to be true to his conscience. He fanned into flame the gift given him, even when it burned him. He suffered in many of the ways that are common to the human experience: poverty, unrequited desire, ignominy, rejection, guilt, isolation, despair. Yet his particular poetic gift cost him; he counted the cost, railing against it sometimes as the Old Testament prophets did. When he settled in Berkeley to teach, he assumed his poetic career was over—as he wrote his poems only in Polish, he resigned himself to being hidden from the world. Few American readers knew Polish, and his works were banned in Poland. During his many years of poverty and obscurity, he must have felt as if he were screaming into the wind.

Despite this, the poet Edward Hirsch says Milosz yearned and strove for “a poetry that was no longer alienated.” By this he meant poetry that was not self-absorbed, but that could locate itself in history and that was rooted in reality. He sought a poetry that could bear the weight of its moment in history, that could “shoulder the responsibilities of its time.” He knew that “One clear stanza can take more weight / Than a whole wagon of elaborate prose.” Alienated in one way or another for most of his life, Milosz insisted that poetry deal with realities, history, and an absolute point of reference, which Milosz unequivocally states to be God.

As alienated as I often feel, Milosz helps to anchor me to realities that are there, and that are broader and older and deeper and more consequential than my life. When I write, I am inspired by Milosz’s continued search for “verbal precision and clarity, a humane art.” Like him, I distrust attempts at “pure poetry” and asceticism for its own sake, views Milosz mocked as adolescent. There remains something profound and real to be known, to bear witness to, beyond “mere” language and craft.

Much of his poetry bore his sense of calling, but it also functioned as a strong rebuke—of himself and others. He could be hard. Yet he was as hard on himself as he was on others, particularly when it came to being true to reality and to consistency between one’s beliefs and his or her artistic or literary work.

Milosz was afraid, yet brave enough to follow where reality led—however, he was frequently tortured by it. He was all alone—alone with himself, his brilliance, his presentiments, his sins (and he called them sins), his discernment, his longing, his pride. Kirsch says, “It was his lifelong, intimate knowledge of suffering, both private and public, that did the most to shape Milosz’s work.”

A question I often ask myself: would I even have liked the man? He could be arrogant, harsh, critical. He was a man of contradictions: spiritual and sensuous; faithful to his conscience regarding his poetic vocation and intellectual career, yet unfaithful to his wife; willing to lose his career to be true to his conscience, yet longing to be recognized for his contributions and work; “not always comfortable with his religious inheritance” and yet unable to abandon it, in a sense championing God before the world. Milosz was one who raged against the reductionism of the modern world that separated the material or physical from its analogical, spiritual esse (i.e., being or quiddity), yet drawn toward Gnosticism and neo-Manicheism.

Related to this last point, Milosz intuited the analogous quality of reality: the understanding that everything in creation is both itself and that it contains an essence, an ontological quiddity that illumines a deeper truth (he was a Thomist). This view resonated inside him:

Ultimately, only a time measured by sacral standards, and not mechanical clock-time, can sanction a belief in the reality of things. A sunrise or sunset, such mundane acts as making coffee or mushroom hunting, are both what the reader knows them to be and a surface bespeaking a sublime acceptance, one to animate and sustain the imaging.

He believed—against his own recurring doubts—that “the trees and rocks speak to us, but we do not understand them.” He hearkened to poets such as Dante and Homer, for whom “the Earth is not empty, because the currents and whispers of heavenly forces run across it.” Milosz grieved modernity’s disenchantment, or separation of material things from their deeper symbolism, wondering if “this moment that has carried us away toward absence, toward dispossession, toward the not-quite-corporeality of the imagination [is] something that is not irrevocable.” And he saw this tendency in himself as well as in the world. He raged against the reductionism of the modern world, trying desperately not to let himself—his mind, heart, and spirit—be separated or dichotomized, defined by one idea, one realm, one method.

Though Milosz was frequently vulnerable and honest about his own sins—in letters to friends and colleagues, in his own poems, in his essays—he drew courage and vision from Jacques Maritain’s ideas on the artist’s task, never letting go of the burden and calling that it must

attempt to capture the intense light of transcendental mystery, and, at the same time, to present a singularity and uniqueness of an individual being; and the basis of poetical energy was love for people and love of the world. The poet himself was to be “above all and primarily a person who reached into greater depths than others and who discovers in reality the radiance of the spirit.”

(Franaszek, quoting Jacques Maritain)

Fundamentally, poets must pursue questions related to the substance of the human being and reality, being brave enough to follow where that search leads. When poets en masse lose faith in a reality outside of “mere” language, that loss is evident in their work, and the end result is that people become indifferent to poetry. “The pursuit of a truth that is otherwise impossible to express used to be [poetry’s] raison d’etre,” Milosz wrote. And if there is no meaning outside of the poem (or other work of art), it “gradually loses all its charm and receives its just desserts: indifference.”

Despite all he lived through, Milosz remained until the end mesmerized by and grateful for the wonder and beauty and goodness of the world, sensing a sacramental quality to all of reality. Kirsch writes,

Unlike many great twentieth-century writers, who saw truth in despair, Milosz’s experiences convinced him that poetry must not darken the world but illuminate it. . . That decision for goodness is what makes Milosz a figure of such rare literary and moral authority. As we enter what looks like our own time of troubles, his poetry and his life offer a reminder of what it meant, and what it took, to survive the twentieth century.

Was it his commitment to truth in art that ultimately preserved his faith? Perhaps—God may have worked in that mysterious way. He seemed, late in life, to come to an acceptance, a peace, and he embraced more fully his Catholic faith. In the end, he went quietly, full of years, absolved.

In A Book of Luminous Things, Milosz expressed his belief that his poetry “remained sane and in a dark age expressed a longing for the Kingdom of Peace and Justice.”

I read those words from a fellow exile as a benediction upon my own poetic vocation.

Image Credit: Polish Landscape via Pixabay

This is wonderful and feels so timely.

Comments are closed.