Tree tipping. We lack a more eloquent term for it. In March 2013, I was a freshman in high school and an avid hobbyist of this obscure pastime, curated to near perfection with my companion and fellow oddball, William Joseph Ellison. My parents were out of town for the weekend, which meant I was to be sent to the Ellisons, a farmhouse tucked in folds of cow-trodden green country in southern Oklahoma. Their property housed miles of barbed wire fence, swarms of blackberry bushes as garrulous as cumulous clouds, finely carved streams and shallow ponds, and most importantly, a grove of limber ash and birch trees.

Will and I had been professional tree tippers since the inception of our friendship. It seemed the only sensible thing to be when you’ve got nothing but time and a field with young trees undisturbed by the broader world. We considered ourselves geniuses for figuring out what probably thousands of male predecessors have already discovered—that climbing a thin ash tree to its very top will bend the organism down, giving you an arch that can lift you feet off the ground with just the smallest jump. Tree tipping. It’s the most natural sport known to man. It’s what Adam did in the garden before Eve preoccupied his attention. It’s what Narcissus did before he ducked downward and noticed his face in a puddle. It’s what bored boys do when the parents are out of town.

The grove stood just a couple hundred yards beside the Ellison estate, obscured by the slow ascent of loping prairie grass. I remember it pocked with holes from moles, gophers, and cow hooves, and the sweet swell of manure patties as plentiful as the Israelites’ manna in the wilderness. In the summer, that whole field chirped with grasshoppers and wasps. It was a verdant world, all the good earth Oklahoma might be known for if people took the time to stop there on their cross country escapades.

But it was March, that ambiguous season of transition, another mild winter not quite relinquishing its grip to the pull of spring and summer. It was a brittle day. Not cold, but overcast, heavy with the freshness of the world of good things, ready adventure. Childhood.

We got to the grove and got at it. We had the afternoon but were due at the church gym that night for basketball and nerf wars. It was no time for idle chatter.

“Hey, what about this one?” Will felt the trunk of a thin ash tree on the far side of the grove. We had walked through the trees, over the decaying ribs of old timber and some bones where an old steer once went to die.

“Looks good! I’ll get this one over here.” And up we scampered, like the neanderthal before the invention of conscience.

Have you ever seen tree tipping in action? I’m not practiced now, but basically, all you have to do is become fifteen years old again, hitch up your heels on either side of the tree trunk with a firm double handed grip above your head, and shimmy upward with a sort of explosive caterpillar muscularity. And then, once you’re at the top where the tree’s body thins and wans out into nebulous branches, your weight lowers you down, hopefully all the way to the ground. Then, the tree is an arm and a trampoline and nature’s primal lever and pully system. It’s one of the most elating experiences I’ve ever had, and I’ve been to Yosemite.

Will and I both knew that the younger, thinner trees were the best for the sport. They bent well without breaking and were supple enough to lift you back into the air when you jumped. But arrogance comes before the fall. We found an older thicker tree with scales of bark and knots denoting its brittle center. But it was tall. It was one of the grandest trees in the grove, somewhat set apart from the rest, proud at thirty feet, waiting to be conquered. God warned there was one tree Adam and Eve ought not pursue…

By now our tree tipping had evolved from the innocent telos of fun and into something more economical. We knew that this thick old ash tree, a cousin of Robert Frost’s lovely birch, wouldn’t hoist us as high as its younger siblings. We knew that it would be a tough giant to subdue. But we were connoisseurs of the craft now, weathered professionals. It was time for a challenge, an exploit to prove our expertise.

I went up first. Here my memory is a bit foggy, but the main thrust of it is this—at just 115 pounds, and the unwillingness to test the higher, spindlier boughs, I stopped at a forked intersection and reported to Will, who would go after me, that this bugger wasn’t going down easy.

“Well,” said Will. “Guess I’m comin’ up, then.”

If we had read a handbook, we would have come across the dangers of doubling up. Tree tipping, while it thrives off the encouragement and company of a fellow tipper, is a solitary game. It’s man wrestling nature, or Jacob wrestling God’s messenger—a perennial struggle of flesh versus spirit, order seeking to tame the chaos.

“You better not, Will,” I said.

“You won’t be able to tip it from where you’re at,” he said, and truthfully so. My boyish frame could hardly alter the tree’s geometry at all. So, up Will came, an addition of about 140 pounds, the first ever double-teamed tree tipping expedition known to the human race.

Will didn’t share my caution against the higher things. He clambered over me and was able to cling to the tree’s pinnacle just a couple feet above me; the hardy plant leaned, as if uncertain of its kiss with the earth, and then levelled out at a noncommittal ninety-degree angle. And that was it. Will had his ankles straddled and crisscrossed over the tree branch, hanging upside down like some docile sloth, except with his tense arms locked and his head swaying backward, giving him an upside perspective on our tree grove.

“You gotta climb, now!” he heaved. “She’s almost there!”

“All right!” I said, now excited at our prospects. “I’m coming. I’ll take it slow.”

And I did take it slow. I proceeded with my hands gripping both sides of the tree trunk, balancing on the rubber tips of my Converse shoes. Will was a dangling arch below me, and I was a wobbling arch above him, idiot boys with an adventure to docket. We were almost even with each other, our goal nearing fulfillment, when …CRACK!

I can still hear the breach of that mighty tree’s trunk, split at the midsection, its top half hanging on by just a filament of bark. A split second later, Will and I had fallen the fifteen feet to the ground, me on my side and Will on his back, like a downed raven. I was winded and jarred, but Will was pulverized, with the tree branches laying over him and the world going dim and hazy above our heads. I was busy nursing a budding contusion in my rump, trying to stand, while Will wheezed to no one in particular, “Help…oh, help.”

I hobbled over to my companion, still struggling to regain my breath as Will fought for just a mite of oxygen. You know the feeling, probably. That suffocating, desperate punch in the chest, the body’s fight for air, the mushed lilt of your brains. Imagine plummeting five feet above a basketball goal and landing on your back, flat as pancake on a griddle. I thought Will’s back might be broken.

“I’ll carry you!” I declared, as Will continued to gesticulate for aid. I figured I’d be forced to be the hero in this saga, despite my own developing injuries, and vowed to haul Will’s wounded vessel back to the farm even if it took everything out of me.

But, as I prepared to haul Will to his feet, we ended up standing together, grasping each other for support. Will, wincing and back bent, stood and breathed, feeling the lower part of his spine with his free hand. My hip throbbed, but we both took a step forward, away from the wreckage. We had run to the grove without obstacle, and we now limped back, interlaced for support.

We relayed our story to Mrs. Ellison, Will’s mother, who laughed and prodded for more detail for entertainment’s sake, then pondered the next steps. She made the maternal decision to drive us the fifteen miles to the Chickasaw Hospital in Ada, my humble hometown of 17,000 people. Will laid back in the front seat with me in the back, feeling a bit hazed, sure, but mainly just worried we wouldn’t be able to play basketball that night at the gym.

Will was worse off than me. He was in real pain, beseeching his mom to go slower on the turns and over the bumps in the road. I probably should’ve stayed in the car but, for glory’s sake, hoped to be more injured than I really was, and so entered the hospital foyer to get checked in. Funny to think that my niece would be born in the same locale eight years later. Time. How it runs with disregard for our memories, but often leaves the world unchanged, or changed imperceptibly enough to escape scrutiny.

After the nurse drew our blood (I still have a maroon dot on the crook of my arm to commemorate), put us in gowns, shipped us through the X-ray room, and left us to await our results, I felt sure that Will would bear the worse diagnosis. He got the hospital bed and I just sat on the chair while Mrs. Ellison texted updates to my mom.

But when the X-rays came back, the nurse reported no broken bones for Will. No misplaced spinal disc. Nothing. For me, though, she announced a hairline fracture in my hipbone.

“It’s nothing serious,” she said. “I just wouldn’t play basketball on it anytime soon.”

So our evening plans were dashed, and I got what I deserved for climbing the forbidden tree.

The main image that sticks with me to this day is Will Ellison walking into the living room the next morning with a cane. We watched The Avengers the night before, and the following Monday, sheepishly told our basketball coach the reason we couldn’t practice that day.

“You were doing what?” Coach asked.

“Tree tipping.”

“Tree tipping.”

“Yes, sir.”

With just one fall, Will and I were transformed into something like old men with a story to tell and a fallen legacy.

It’s always hard to pinpoint your transformations. A real-life story defies a neat plot structure. All I know is that, despite how much fun it was to fall out of a tree and live to tell the tale, I’ve never been tree tipping since. I’ve climbed trees all over. There’s a gnarled post oak brooding over an old beaver dam by a lake where I grew up, furnished with a perfect throne of a branch. I climbed trees on the lawn of Wheaton College in front of Blanchard Hall, depressed and wondering whatever happened to childhood. But bending a tree all the way over into a limber arc? It’s been a decade since I last made the fifteen-year-old’s ascent. Why?

Maybe it was the advent of a high school career, which would come to be marked by spiritual and mental confusion and the onset of a melancholy that I’m still trying to fully shed. Was I to be regarded as a basketball player or as an imaginative writer? Did my emotional sensitivity make me a faggot, a weakling, and a fluke? What about all these changes in body, voice, and spirit? I settled on the written word over the hoop, choosing to hurl my world at the blank page and try to make adequate sense of it. Whether writing alone can do this remains a half-solved mystery. Like the old ash tree in Will’s pasture, life had ruptured, and I began to feel like I had lost something essential before it was even mine.

It happened March ten years ago. This isn’t an essay intended to nostalgically pine over the past. But there are these breaks in life—like Frost’s ice storms—that send you hurtling to the ground, and a decade later, you have to wonder, you have to write it down, and ask, when did it all change?

I went back to the Ellisons my senior year of high school just a few weeks before graduation. Will showed me his heated pen of new chicks in the garage, and we ate some nachos and chili in the kitchen. We always talked about going back out to the ash and birch trees. We talked about hiking out there that afternoon to take another look at the fallen beast. I don’t have a memory of what it looks like in its broken state. Maybe it’s repairing itself, shedding the deadwood. We sat down in Will’s living room, eighteen-years-old now and on the brink of new ruptures, new lives. He was going to be an engineer. I was going to be a writer. We didn’t hike back to go tree tipping.

We just talked.

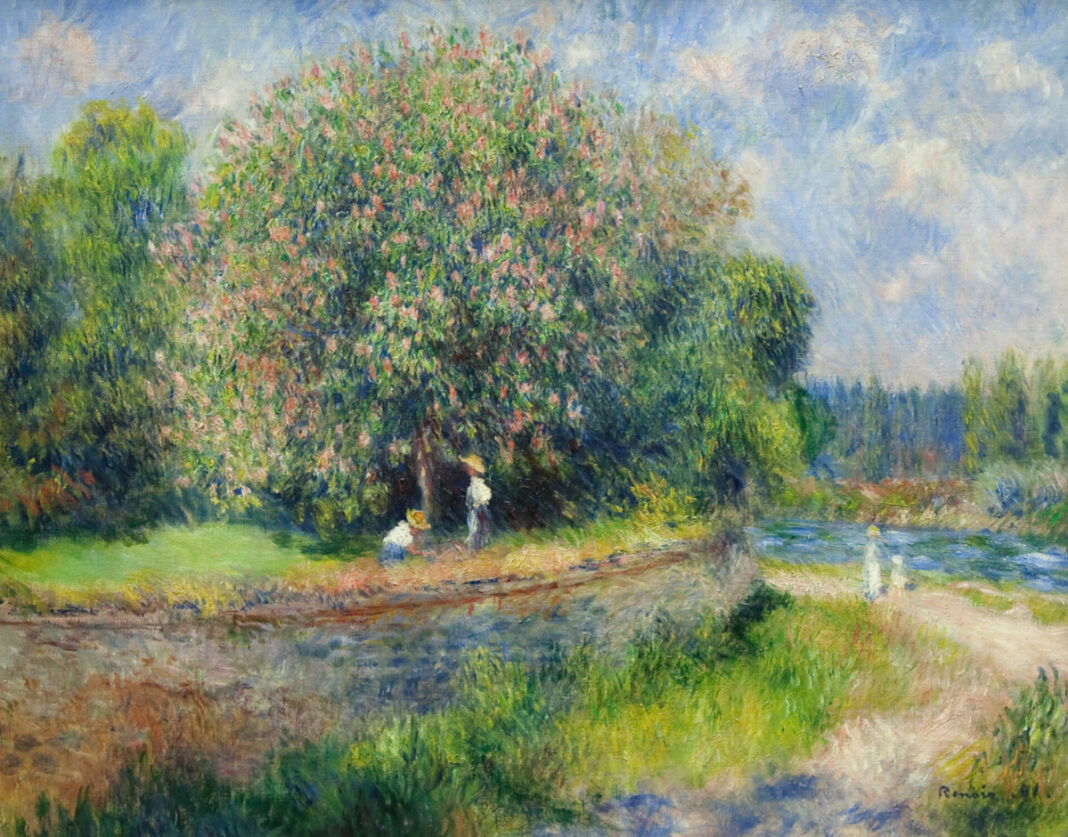

Image Credit: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Chestnut Tree in Bloom” (1881).