Recently, as my husband had just finished backing out of our driveway with our four-year-old in the car, she suddenly piped up with her little voice: “daddy, can I watch that movie again?” With surprise, my husband realized that she was referring to… the car’s rear-view camera. Deprived of all on-screen entertainment for most of her life, she found even the few seconds’ footage of the street view behind the car to be exhilarating to watch. The incident was funny, but the questions it brings up about how we fill our time and our minds in this post-industrial media-saturated age are decidedly less so.

In her best-selling book, Cribsheet: A Data-Driven Guide to Better, More Relaxed Parenting, From Birth to Preschool, economist Emily Oster addresses this question as she works hard to dismantle fears fueled by the mommy wars over a variety of parenting issues: Breastfeeding or bottle? Stay home longer with the baby or go right back to work? TV for a limited amount of time each day or week, or no screen time at all? Of the entirety of Oster’s book, it was her response to this last issue in particular—that of screen time—that I found especially significant. Oster suggested that instead of fighting over the least damaging quota of screen time per day or week, it is better to ask what else is squeezed out if the kids are watching television instead.

This is a useful reminder for all of us. There are only twenty-four hours in the day. Most of us spend maybe six to eight of these hours sleeping—at least, we probably should. For children, the number inches closer to ten to twelve or more of these hours, depending on the age. Teens need almost as much sleep as toddlers, by the way, although most of them do not get it. Then we spend another eight to ten of these daily hours at work and commuting to and from work—or, likewise, at school and related activities, in the case of most kids. This doesn’t leave a lot of hours for other activities, so how are we using those precious few hours that are left?

Every minute of our lives, whether we are parents or not, we make choices, some consciously and others passively. Every minute that we are engaging in one activity, we are not engaging in something else that we could have been doing instead. This really is a zero-sum game. Adding further pressure, as the clichés remind us, is the reality that time is a thief. Babies don’t keep. Every minute matters. As one of my college professors was fond of saying, “every minute of your life that you are not studying Greek, you’re forgetting it.” No pressure.

This weight of responsibility for how we use our time is a biblical concept as well—it is the notion of redeeming our time, remembering that it is a precious and non-renewable resource, given to us as a precious gift for only so long and for good works. Our mortality is simply a fact of life, and this final limit heightens the pressure yet more.

The choices we make for our use of time are important. But the reason they are weighty is not purely or merely a calculation of the finite nature of time for us, mere mortals, children of dust, feeble and frail. Rather, these choices matter because of how our use of time shapes us as beings with a mortal body yet an eternal soul. That with which we fill our time, after all, is what ends up filling our minds, hearts, and souls. More than simply responsible scheduling, our very character is on the line, and that has consequences far beyond the present.

There are, for any given moment, many wonderful and less-than-wonderful things we could be doing with our time. Let us consider one of the latter. The latest statistics suggest that twenty-three percent of American adults watch Netflix every day, averaging sixty-nine hours of streaming per month, some even streaming it during work. Others do not watch it every single day, and others simply use other streaming services. Between one thing or another, though, we are a nation of passive entertainment, and this has significant implications for our character formation. While there are plenty of useful or wholesome options on Netflix and similar streaming services, much of the content is decidedly unsavory. It could, in other words, if ingested habitually and in high quantities, have a negative effect on one’s mind and soul. Perhaps, also, there could be further negative effects on the body, for watching a movie is yet another sedentary activity, and most of us have plenty of those in our lives already, thanks.

And so, we are getting to the crux of the issue at hand: assuming we accept that it matters how we fill our time and our minds, just how exactly do we make the determination for what is the best use of our time? I propose two chief criteria, considering specifically content and relationships.

First, when it comes to filling our time and our minds, we want to start with things that are good and beautiful in a sense that is greater than our own age. There are so many beautiful books out there, many more than we could read in our finite lifetime. There is, furthermore, great art to experience in museums and at concerts and dramatic performances. We can also make art ourselves for our own joy. I think about the hours each week that my daughter spends painting and coloring. I enjoy it even more now that she seems to have moved on from painting and writing on the walls. My middle son just performed in a children’s community theater musical production that required him to memorize close to eighty lines of text, some of it set to music, and learn the choreography. I have rarely seen him as happy as he was while working on his role. Finally, we try to spend at least two hours outside each day, usually at a playground or park. I could talk about the scientific benefits of physical activity and fresh air, or I could just say: everyone is in a much better mood and sleeps better at night whenever we get plenty of time outdoors.

With the availability of activities that require us to engage more actively with the beauty of this world and the echoes of God’s imprints upon it, I haven’t seen a movie in about a year. For several years now, in fact, I have been averaging about one movie per year, usually choosing materials I considered essential for teaching. Now that I have quit academia, I may never need to see a film again, which is a rather appealing thought. Of course, to be fair, I do spend a good two or three hours a day on my computer—writing, editing, responding to emails, and checking social media. My life is assuredly not screen-free. But it is free of on-screen entertainment, and the same largely applies to my children, who only get to watch a film once every few weeks as a special treat. Although, apparently, in the meanwhile, they get to enjoy the best that the rear-view cam in the van has to offer.

Second, relationships matter. Dan and I try to prioritize the things we can do for and with others, whether in the family or outside the home, over solitary activities. We were made to live in community, in relationship with family, friends, neighbors. One of the problems of a passive entertainment activity, like Netflix, is that it takes us away from interactions with others. Watching something can be done in company with others, but it will never be the same kind of togetherness as we have when we sit down for dinner with family and friends, play a board game, read a book out loud for each other, or go for a walk as a family.

My point, ultimately, is not to wage a war on Netflix. I am merely using the most famous and most popular of the American streaming services as a representative of the larger problem of the desire to disengage. The idea of relaxing and enjoying one’s well-earned rest has biblical undertones—the Sabbath is a key theme; even God rested. But the Sabbath was never meant to be a time of selfish retirement from all relationships, nor was it made to be spent on diversion or amusement. At the same time, however, I want to be clear that I am not advocating here for the industrial-era idol of squeezing the utmost out of every minute. Rather, I want us to think about who we become, and (for parents) who we cause our children to become, through how we use our time.

Decades ago, I read a striking book that clearly stuck with me: Momo by the German children’s novelist Michael Ende. It is a cautionary tale of a society much like the one in which we live today. In it, people ignore friendships and beauty in the world around and only care about maximizing profit, squeezing each minute for all it is worth. Mysterious grey-suited men begin stealing time from such people, preying on the natural human desire for profit. An apocalypse of sorts appears at hand. The heroine of the story, Momo, is an orphan girl who is the guardian of joy in her community. A friend to all and known best for her gift of listening to others, she ultimately defeats the grey suits in the novel’s dramatic final showdown, restoring a world in which people want to delight in each other, in beauty all around, and in time spent together.

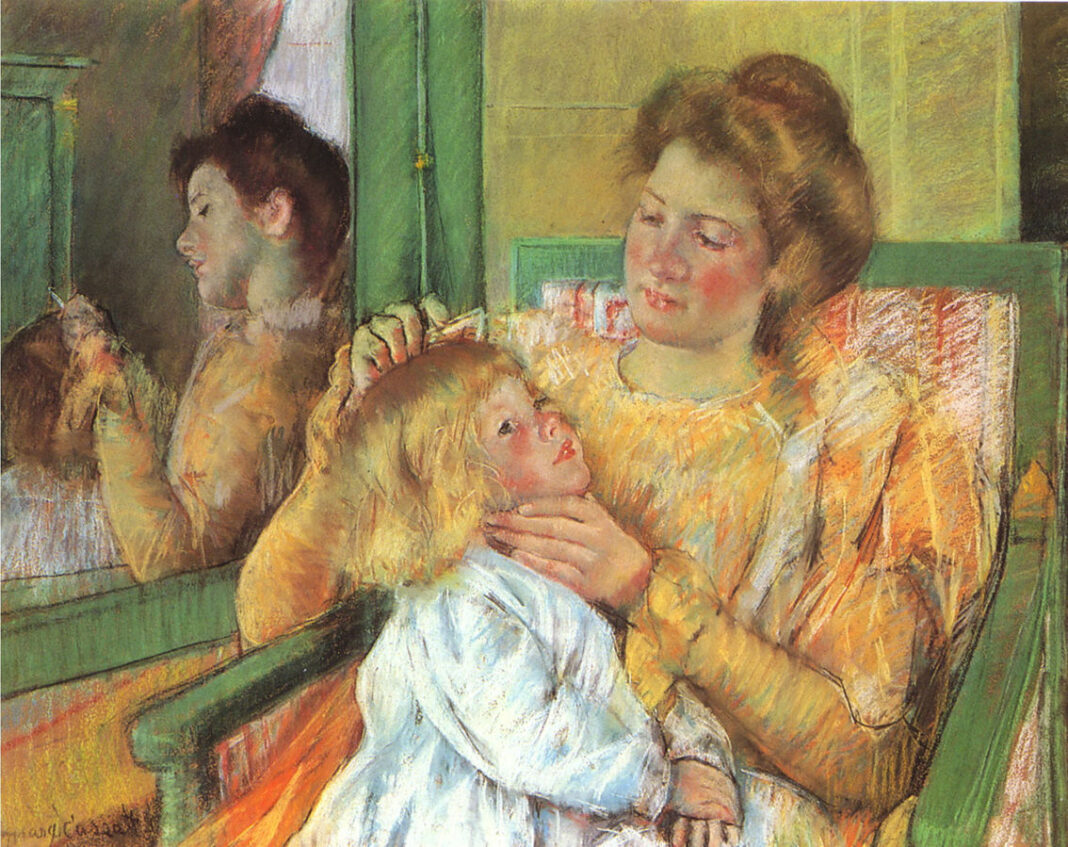

Image credit: “Mother Combing Child’s Hair,” 1879 by Mary Cassatt via Wikimedia