I was wearing Army fatigues and standing below Virginia’s Natural Bridge when I caught my first trout on a fly rod. I threw my clumsy cast under the watchful eye of George Washington’s initials and the Department of Wildlife foreman, Gill, who directed our efforts at clearing overgrowth and warmly told me, “Johnson, you’re a gangly son’a bitch.” I caught a plump rainbow trout that was stocked for a youth event (normally fishing isn’t allowed at Natural Bridge) but had evaded the panoply of bright-colored Powerbait that proved too alluring for many of his siblings to resist. My friend and fellow VMI cadet and fly-fishing instructor, Mason, patted me on the back. And so it began.

After graduation, I seized every chance to loaf in the hills and forests of the New River Valley. The fish were generally sympathetic to my novice efforts as I explored tucked-away Appalachian streams or waded out into the mighty New, whose rocks and currents stretch back languidly into the past. The New River, despite her name, is the oldest river in North America. In the world, she is only younger than the Nile.

Any fly angler will assure you that while fish are indeed indispensable to the activity, fly fishing is knit together by something other than the dance between angler and fish. This something, like any meaningful experience, is felt before it can move toward articulation.

I can coax such something when I recall descending the narrow game trails to Tom’s Creek. My rod is outstretched like some antennae or stiff whisker. I try to pass the poison ivy unscathed. Through the dense Virginia undergrowth, I see a first glimpse of water, a dark seam curling against a boulder before spreading its tendrils into a changing number of rippling channels. My footsteps slow. My eyes become birdlike, searching for any flash of silver bellies in the gurgle. I send my fly line through the eyelets in a few false casts. This initial seam is a welcome mat, a warm-up, the plucking of orchestral strings before a performance. It’s a preparatory threshold for the main event: fishing the convergence of Tom’s Creek and Poverty Creek, which gently churns a hundred yards downstream. The fly drifts the seam without a greeting. I enter the creek and splash some water on my calves, rinsing—I hope—any malevolent oil that clings to my leg hair.

My initial steps downstream are noisy and sloppy. I want to sprint but I restrain myself, chanting inwardly “slow, slow.” The outstretched branches of oak trees and pines create a low canopy. I creep toward the eddy, impatiently gaining ground toward the few spots from which I can make a cast. A few flicks later, the “blue winged olive” touches the water. The water molecules rally together to hold up the string and feather before passing it along. In this moment, as the drift begins, everything falls silent. I don’t hear the birds. I don’t notice myself breathing. I don’t notice where my arm ends and the fly begins. The entire world seems to rush into the drift. Everything is transfixed without stopping. I am not annihilated by some dissolution of the self; instead, I am drawn forth to face that emerging something.

One could describe this instance anatomically, psychologically, philosophically, or spiritually. The convergence of these axes indicates a direction that seems to be best articulated as a certain posture toward the world, a type of taut receptivity.

American philosopher Henry Bugbee described such a posture in his most famous work, The Inward Morning. He writes of an “alert openness” that presupposes our twofold modes of contemplation: perception and reflection. This openness, or ingatheredness (taken from Gabriel Marcel), describes a condition that enables the possibility of true thinking. He offers fly fishing as an example. He compares the alertness to “keeping our fingertips right on the trembling line.”

Bugbee’s association of fly fishing with this foundational posture is partly directed by his broader reevaluation of epistemology. He writes earlier that our reflections about reason have been unhelpfully focused on “statements” rather than “partaking in the experience of live thought.” He instructs us that we would do better to reflect on the experience of playing tennis, or any game with a “measure of alertness and gracefulness and absorption.” He immediately gives an example of a Native American boatman, who masterfully navigates a river. The river was a special geological feature for Bugbee. He saw in it a deep metaphor of reality:

the reality of a river carries with it the sense of reality as I would do justice to it… It seems that there is a stream of limitless meaning flowing into the life of a man if he can but patiently entrust himself to it… There is a constant fluency of meaning in the instant in which we live. One may learn of it from rivers in the constancy of their utterance, if one listens and is still.

This entrusting stillness is another way to understand alert openness. Both recognize the constant fluency of reality and its overdeterminate, saturated nature. We can never ossify the world because it is always moving and changing like the river. Yet we can open ourselves to this ever fluctuating movement. This is manifested in the moment when the angler, fly, and fish are suspended together, held as with the fragile tension of water molecules. This is that something.

Such a posture toward the world is sorely needed and sorely absent. We find ourselves too often in a state of alienation from both the world and ourselves. Regardless of your particular theoretical persuasion (Emile Durkheim’s anomie, the Frankfort school’s historical materialism, theories of neo-liberal decline, Byung-Chul Han’s deterioration of ritual, Hartmut Rosa’s concept of acceleration), alienation has remained the primary exigence of modern and post-modern Western culture. Although it has assumed a number of varying manifestations, the central issue remains: we feel as if the world has become silent.

One can turn to that harbinger of the coming crisis, Nietzsche: “Nobody speaks to me but myself, and my voice comes to me like that of a dying man… My heart refuses to believe that love is dead; it cannot bear the horror of the loneliest loneliness, and forces me to speak as if two.” Here, the kosmos is emptied of meaning and structure, leaving us alone in the void. If we want to cling to those threads of meaning, we must rend ourselves in two, producing this schizophrenic dialogue.

Bugbee recognized the plight of alienation. He recognized what he called a “condition of exile,” an existential throwness into the world. Despite such an exile, he refused to abandon the kosmos of meaning. He considered the possibility that the world had not grown silent, but we had grown hard of hearing. Yet, our ears are not so dull that they are completely deaf, and our whispers, though quiet, may not be meaningless. In the face of alienation, we can “open ourselves to the meaning of a life in the wilderness and be patient of being overtaken in our wandering by that which can make us at home in this condition.”

For Bugbee, the wilderness was both physical and phenomenological. The latter indicating the overwhelming waves of meaning that cannot be quantified in daily life. Both the excesses of the natural world (the physical wild) and everyday experience teach us our limits and the mystery that lies outside our limits. Recognizing wilderness can help us escape the alienated paradigm that sees only function, price, and utility. It can unplug our ears to a kosmos of meaning.

Notice that we do not climb out of exile ourselves. We do not, as Beethoven so zealously noted, seize fate by the throat. Instead, we cultivate a stillness in which we are overtaken in our wandering. We stand receptive without being empty, passive without being inert. In the words of another philosopher in Bugbee’s theoretical circle, Martin Buber, being “comes to fetch you,” to fetch you home. Wilderness becomes a type of homecoming.

I climb into the car. Drops of water hit the floor mats. The air is hot, and I roll down the windows. As the loose joints of my old Dodge Intrepid bounce along the switchbacks, I turn up the Willie Nelson CD that’s been lodged in my car all summer. He plucks his guitar with that notorious idiosyncrasy and whines a melancholy narrative, “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground.” The trees cast fluttering shadows across the hood and bits of gravel fly on short trajectories away from the tires. I realize that I’m hungry. If it doesn’t rain tomorrow, it would be a good day for fishing. Maybe I can sneak away after work. The angel has departed, but the vision lingers.

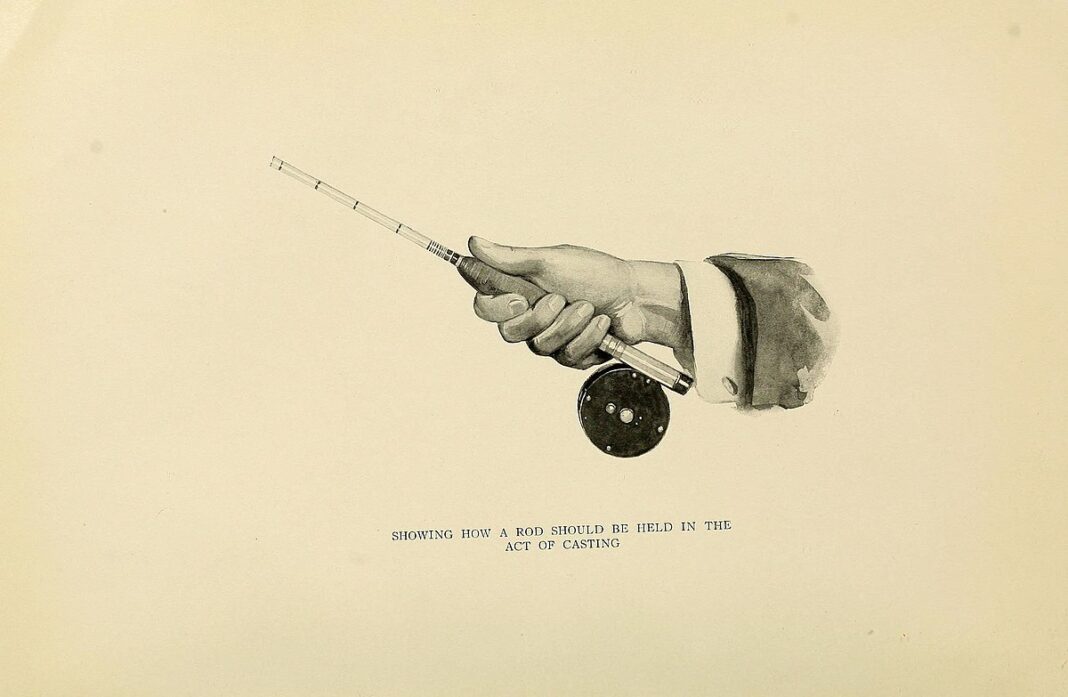

Image credit: “Trout Fly-Fishing in America” via Wikimedia Commons

This is as fine a piece of writing as any I have read, on fishing or any other topic.

Comments are closed.