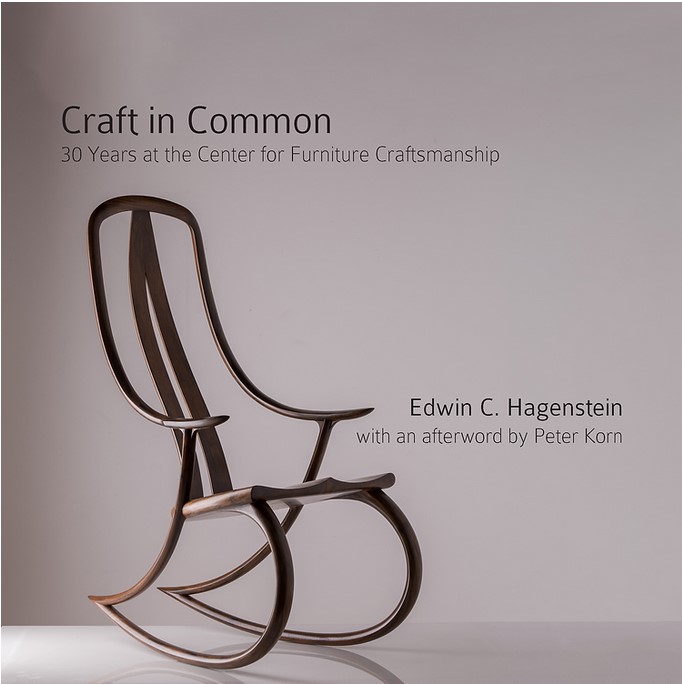

We all want the things we build to outlast us. Whether it be a family legacy, something we’ve made by hand, or a community project, there is an innate desire to pass down something tangible and meaningful to those who come after us. Yet making this actually happen is not easy, especially when it comes to institution-building in an age where institutions seem to be crumbling and trust in them is at historic lows. The new book Craft in Common provides a positive and inspiring account of how an institution can be built to survive and thrive, even today. In the book Ed Hagenstein tells the thirty-year history of the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship, from its humble beginnings to its renowned status in the furniture-making world. Incorporating countless interviews, lovely photos, and his own personal experiences at the Center, Hagenstein weaves together a beautiful story of an institution done right. As he puts it, “from very modest beginnings in 1993, it has developed into one of the best and most consequential woodworking schools in the world. This is no mean feat, and when an institution functions so well, it is worth taking a close look to see how that happens…. In a time when institutions seem often to underperform, the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship offers hope” (4-5).

Being a furniture maker, I found myself especially drawn into the story, as I recognized many of the individuals involved in the Center from decades of reading Fine Woodworking Magazine and other Taunton Press publications. The book’s elegant design and layout—including a healthy dose of high-quality photography—is fitting for a book chronicling an institution devoted to fine craftsmanship. What struck me most in reading the book was the role of risk-taking and personal leadership in an organization’s founding phase, and the necessity of consolidating and institutionalizing its vision, so that it outlasts its founders. Such lessons have applicability far beyond the world of furniture.

The Role of Risk-Taking and Personal Leadership

The Center’s origins can be tied in large part to the inimitable Peter Korn, who has done perhaps more than any other living person to revive the craft of furniture making for a new generation. Korn singlehandedly started the Center, and Hagenstein’s recounting of the story highlights the twists and turns along the way, including aspects of Korn’s own life story. From Ivy League roots and 1960s counterculture, Korn turned towards carpentry and then furniture making. Korn spent several years teaching and working at Anderson Ranch with legendary craftsmen Sam Maloof and Art Carpenter, but he eventually set out on his own to pursue his distinctive vision for a center devoted to the dignity of designing and building useful things, centered on Korn’s three core values of integrity, simplicity, and grace.

On a shoestring budget with his personal money, Korn started the school in conjunction with the release of his 1993 book, Working with Wood: The Basics of Craftsmanship. Students, ahem, came out of the woodwork to attend, giving Korn enough proof-of-concept to keep going. In its early years, the school’s signature program became its 12-week course, which began incorporating notable visiting instructors such as Michael Fortune, James Krenov, and Alan Peters. Interest in the Center grew rapidly as did waiting lists for its programs. By the late 1990s, the Center had a beautiful 12-acre property and was growing. Korn’s vision was becoming a reality. But how would it grow from being one person’s dream to being a sustainable and viable institution?

The Institutionalizing Phase

After the early success of Korn’s upstart, his personal bouts with Hodgkin’s Disease sparked a restructuring of the Center to ensure it would outlast its founder. This included incorporating as a non-profit organization and the formation of a board of directors. Surprisingly, Korn’s health rebounded as he beat the odds multiple times, allowing him to play key roles in the ongoing identity of the Center as both an instructor and as executive director from its inception until 2021. Korn helped form an outstanding board that included experts in craft, fundraising, and business that were committed to the Center’s vision, many of them even attending its programs before joining the board.

The lessons here for institution building are many. Frequently an organization starts around a charismatic figure but fizzles out after the initial excitement, or when the founder moves on. Putting structures in place to implant and replicate the organization’s DNA is vital to its survival. So too is fostering a community that shares the same vision. The Center has continued to do this through the careful selection of visiting instructors, the variety of courses that reach different markets, and a fellowship program to ensure a continuation of the vision, while encouraging cross-pollination to keep the organization from becoming stale or inbred. The Center also has created a furniture gallery to showcase some of the best of the Center’s work and other important work from around the world, which holds exhibits that are open to the public. This is just one of the many ways that the Center has nurtured healthy relationships with the local community, so much so that several students have made their home in the surrounding areas as furniture makers.

Additional Themes

Several other themes emerge throughout the book. Hagenstein notes how Korn’s model of servant leadership played a key role in the Center’s success by keeping this question in mind: “do those served grow as persons?” Hagenstein explains:

That Korn led through serving is not to say that he was deferential to others in his leadership. He was, in fact, very certain of how the Center should run, and through his will and example, set very high standards for others to follow. However, by all accounts he strove to use his authority to meet the mission of the school above all, and by doing so, to serve the interests of students, faculty, and fellows there. (62)

Korn’s approach to leadership, which came to be embraced throughout the Center, is a refreshing alternative to the heavy-handed leadership frequently seen in institutions and governments today.

Hagenstein also points to the experience of working in community facilitated by the Center and how it is worth recovering in our day. He notes:

Set among others, we naturally tune into what they are doing and the shared climate has its effect…. We take an interest in what they are doing, wonder whether they are keeping up, and notice when others try something new or different. Working in community can be exhilarating in ways that working alone cannot, and more than one interviewer mentioned the letdown they felt when, after being at the Center, they faced a silent workshop back home. (110)

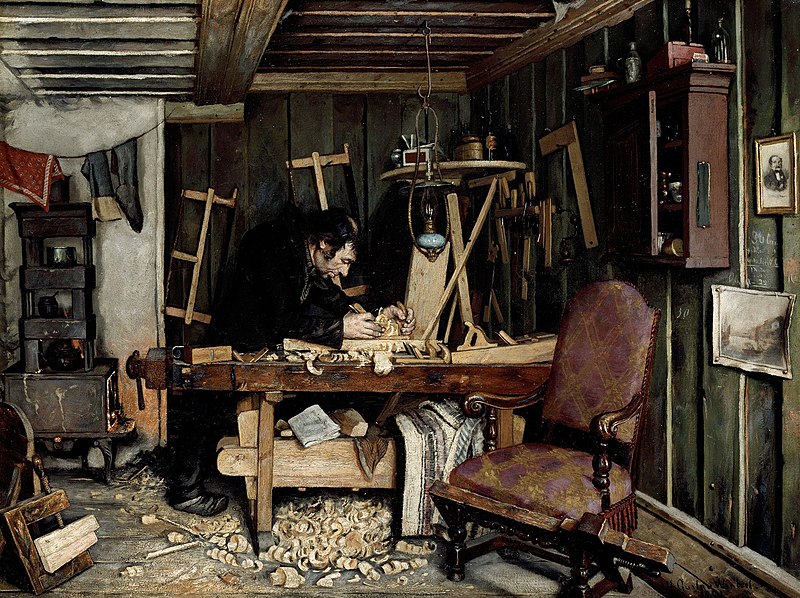

The Center replicates the type of environment where craft knowledge is passed down, much like what happened for centuries prior to industrialization: “an experienced craftsman giving advice to a novice with a half-done work on the bench between them” (91).

And lastly, a theme that undergirds the whole book is the importance of expressing embodied agency in the world, and one way to do that is by making things. Korn’s reflection in the Afterword to the book is apt in closing,

Hands-on, creative work addresses innate psychic needs that go largely unmet in modern life. Corporate work environments and leisure screen time, for example, seem to deplete most people’s senses of personal agency and authenticity. Craft, on the other hand, centers the maker in one of the most vital elements of human nature, which is the ability to change the given world in ways that matter. The challenge of using one’s own imagination and skills to bring new objects into existence can be a wellspring of meaning and fulfillment. (151)

Image credit: “A Carpenter’s Workshop” via Wikimedia Commons