This essay is part of a larger cross-genre work on the watershed of Loves Creek, just east of Knoxville, Tennessee. The watershed is about sixty square miles, a rolling and hillbound countryside quickly shifting from rural to suburban.

The waters of Loves Creek run beside a school.

I’ve gone there at night, sitting near the road, listening to the trickle of the creek, and wondering about the students. Across the streamway from the fancy, newfangled building, there’s a gazebo, broad and virtually abandoned except for the junior-highers who come to sit, rewarded at last with the barest gesture towards being out of doors.

I wonder about them, about their waterside lives within the system we have built for them. Tennis shoes and recycled eighties fashions blend with newly cogent self-awareness, hormonal imbalance, and acne. Their feet grow too large before their bodies catch up, a blessing that prevents them, mostly, from falling over. They spend the day heaped together in an Irish stew of adolescence, sequestered away from the regular continuum of age. It’s a structure dependent on the idea that twelve-year-olds, say, are generally similar when it comes to cognizance. The idea is mostly correct, but what about the times when it’s not?

Moreover, junior high, or middle school, functions as the time when we, as a race of beings, begin to educate ourselves away from play and from applied knowledge. Junior-highers get stuffed into a building where they can breathe filtered air, walk on waxed tile floors, and eat food so far removed from its farm-grown origin as to make real meat and vegetables seem alien, exhibits for field trips.

Why do they do this? What is the point, surrounded by the Tennessee hills, of spending the whole day indoors in an environment so mentally sterile as to stifle real life? “Nature is never spent,” wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins. “The dearest freshness lives deep down things.” So why keep the kids away from it? We answer: schoolwork.

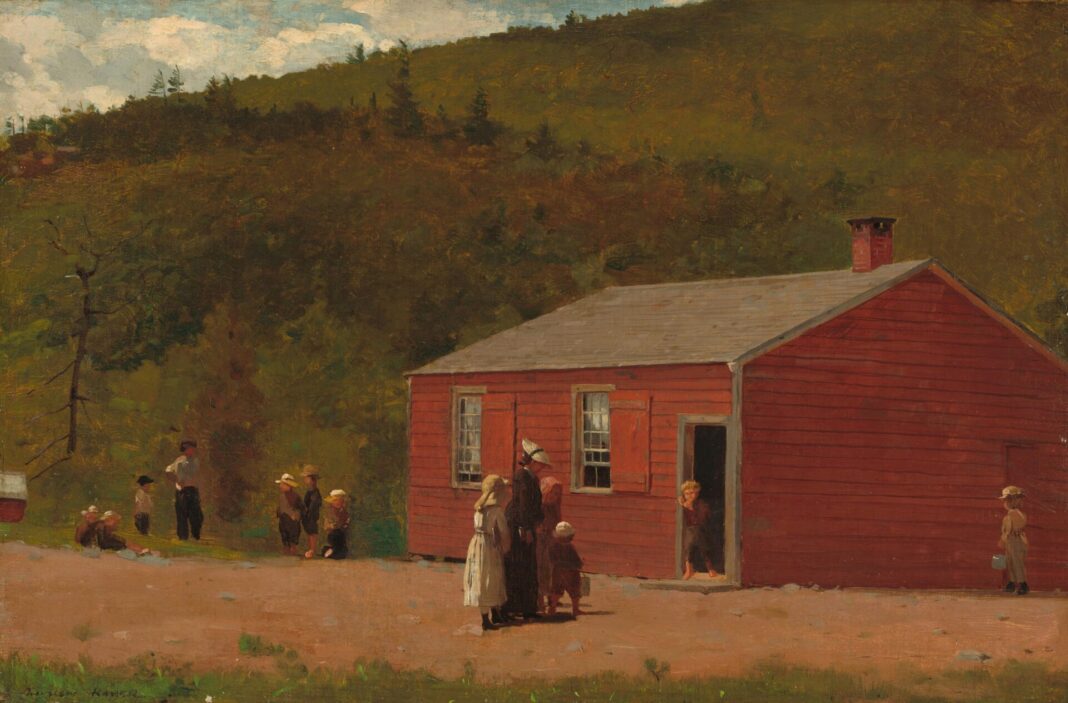

Of course, rather than being done by them, the schoolwork has effectively been done to them, for they are no longer allowed to play. When a few teachers, out of pity and understanding, bring them outside, it seems almost as though the kids have forgotten how. They hardly run or chase each other, and indeed are discouraged from doing so. They certainly don’t dig into the dirt and imagine anything. If they move at all, they walk in circles on tracks like convicts in a prison yard. Fairies, fairy houses, and even mighty pirate forts have been stomped out by industrial education. Don’t look out of the window, the teachers must repeat; attend to your books, your screens.

Yes, don’t look out there. Nothing can be learned from imagining the local past, from embodying the history of those who came before—which, in the case of eastern Knox County, means imagining someone trying roadless to wrangle a wagon down and then up the creek embankments, all to stay alive by finding a farmable patch of ground. This, or someone even more specific. What could be gained by contemplating the Swiss immigrant whose grist mill once served both Union and Confederate troops just a few hundred yards away? Or the old veteran general mysteriously murdered near his home in 1862, just two miles east? No, don’t look out the window. No knowledge, surely, lies in considering the nearby lives of bygone peoples some wooden-souled president sent weeping into the west in the 1830s. Don’t look out the window. Who could learn from watching turkeys gaggle and strut over the unused football field and un-pistoled track? There is no education in the groves of acer rubrum, of quercus alba, spitting keys on the wind and laying a carpet of acorn mast. MIDI can now send computer commands via sonic pitches; what more is there to learn by giving ear to birdsong?

It isn’t all this bad. I know the teachers there. They understand the children much better than the system they work for, and they fight the system in small ways when they can. A science teacher recently got his class outside for a bit of perspective on the solar system. A scale model involved things like a marble and a peppercorn being more than a football field away from each other. Such is the awesome power of gravity in spacetime. Meanwhile, the students were brought outside, where their study could become more connected to life. The unspent beauty of nature that Hopkins saw has much to teach us even if we’re not always paying attention.

But paying attention is always better.

After hours, in the dark of night, the high windows now mirror down on the stream through leaves, even architecture as unflavored as modernity having no skill to flee the bending of water, the shadowplay contrast. Some child will sit here, stealing a moment’s thought from the tyrant called algebra, the bullies with their bulging cheeks and sallow foreheads, the oncoming void of puberty.

Gazebo Prayer

Oh, God, may this be a place

of consideration.

It is shade.

It is respite

amid all impossibilities

of adolescence.

Oh, Holy Maker,

may it be so.

Besides all that is wrong—

the interstate’s endless cussing,

the brakedust smell,

looming tests lacking perspective,

the self newly at war—

may some child find a peace here,

a signature in the willow crosshatchings

calling out your name

like longed-for escape.

This white building,

plastic and aluminum,

is here.

If it speaks not Your name,

it speaks nothing.

So may it speak.

I write a prayer, ecologically, in the vein of Saint Francis. His medieval poem “Canticle of Brother Sun” may seem a little animist to the modern churchgoer (though it isn’t), but it’s in a long tradition of Hebraic and Christian thought and work that looks at the metaphysical through the physical. Moses saw God in the burning bush while working as a desert shepherd. David wrote a famous paean while watching the night sky, aflame in the absence of light pollution. The prophet Amos held down a job keeping flocks and an orchard, work marked by long hours of little conversation. Gerard Manley Hopkins—he of “long live the weeds and the wilderness yet”—was himself a Jesuit priest. Another Jesuit, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, stumbled along the difficult line between Genesis and contemporary geology, all while happily getting his hands in the dirt. At the very least, the Lord, it appears, is not so anti-nature as current industrial church thought would indicate.

If the children go outside to learn, we can rest assured that it will be harder for them to ignore creation’s Creator. I was recently at a wilderness school donor event. One would be hard-pressed to find a more purposefully secular crowd. Yet before the dinner was served, an emcee read Wendell Berry’s poem “The Peace of Wild Things” and enjoined all to take a moment of pregnant silence. Berry himself does not seem a product of the industrial church; yet neither does he shy away from Christology in his work. It was telling to hear him recited at such a gathering. To be out in the world of wild things confronts us with the undeniable divine signature.

My own life tends somewhat, despite my contrarian efforts, towards the suburban and unromantic. On our little farmstead, where people think we homeschool all our children (we only homeschool one out of four), we live on city water and coal-powered steam plants. Would that it were suddenly not so, but the journey towards being better stewards of creation is made of many steps. We take them one by one.

Each year, the maple tree and the walnut trees out back of our Tennessee home serve up gallons of sap to be boiled down into table syrup. This past summer, the walnut trees even became a source of dye. My third daughter is into painting and crafts, and my eldest has an eye for costuming and weaving. Looking towards future skills, I plucked up from the ground the annual wealth of tennis-ball fruits dropped by the trees. We tried to eat the walnuts one year, but working meat out of a black walnut is worse than cracking crab legs. Determined they should be of some use, I put them in an old stock pot with rainwater and boiled it over a firepit into a dark tincture. As a test, I threw in a pair of old cotton shirts, to great success. My neighbor also came over to dye something, making the effort communal.

The unnamed creek below our land, a branch or fork of Adair Creek, is an ongoing restoration project for the family. The kids learn about stormwater, silt, microplastics, rodent tunnels, riparian buffers, and the necessity of praying for rain. Driving along mountainside roads, they watch me collect rocks that have fallen and rolled to the curbs, usually some species of slate. These we take to our creek, pulling up green plastic netting and laying down a meandering watercourse for the next time it rains.

We blow autumn leaves down to what my children call “The Swamp,” perhaps the remnants of an old stock pond, now overgrown with green ash, cottonwood, and poison ivy. The project takes most of my day, if not more. While they’re young, the children glory in the giant piles of hardwood leaves, and as we move the heaps past the garden plots, they learn about allelopathic chemicals. As I direct them from play to work to play again, they learn the value of good labor.

A knowledge that awakens in me more and more is of the farmer’s relation to time. Most of us in the indoor society think of indoor time as structured, while outdoor time is recreational. We spend our “free time” outside. Thus the billions of dollars spent in fancy outdoor gear that would have baffled Sitting Bull, Sequoyah, Daniel Boone, Lewis and Clark, and John Muir altogether. No offense to the makers of helpful things, of which I own a number, but those who consider their outdoor time structured—farmers and foresters and the like—don’t necessarily suffer the form of gear madness that plagues outdoor “enthusiasts.” My brother is in the forestry service and bought me a decent knife. I once bought him a pair of good gaiters. Neither of us would ever consider buying the other a plastic ‘portable’ egg carton, for example (no more portable but far less compostable than the papier-mâché cartons from the store). We would simply see it as indulgent and unwieldy to haul eggs into the backcountry. Still, the brightly colored, sculpted petroleum product cartons find their way onto store shelves next to the cheap steel machetes. There’s a romance that comes with the natural world which can turn into infatuation, often to the natural world’s chagrin. In Americans, at least, it takes on a capitalist or industrialist bent. Time itself is a great example of this.

Think of the difference between a child who goes outside to play (woefully rare these days) and one who goes outside both to play and to do chores (even rarer). The first learns the colorful creativity that arises from boredom and from being surrounded by the endless inspirations and reasonably mild dangers of trees, skies, waters, wind, grass, sticks, and animals. The second child learns all the same things as the first, plus the valuable idea that to be outside is normal.

Imagine a schooling that meshed science with service. The chemistry and biology of composting becomes a way to rehabilitate land, serve communities, and steward the environment. The math of geometry complements the building of a shed or the restoration of a riparian zone. The formulas of physics entwine with small engine repair. There was a sharp divide in my own high school experience between sciences and work, between theory and life. Most of the academic knowledge stayed theoretical by being cloistered in classrooms. By contrast, the so-called dumb kids—those not languishing in precalculus—spent hours in the vocational building, learning actual skills like HVAC maintenance, bandsaw usage, and how not to die while arc welding.

What if learning were removed from hermetic rooms and flung into the fields? Send the mathematicians to 4-H and you get vets and sustainable smallholding agriculture. Make the bawdy humor of Midsummer Night’s Dream tolerable to the shop class crowd from my high school, and you might get modern country music that doesn’t suck. Banish my honor roll English fellows to shop class, and you’ll get the poet B. H. Fairchild. Knowledge, with the benefit of synthesis, verges on wisdom.

Classes like this find far too occasional a popularity, and then mostly in affluent schools. In academic cant they are often termed enrichment. Might then the absence of them—and their methods—be impoverishment? Refuse to let the mathematicians outside, and you will make them poor. Keep scientists’ hands out of the mud, and you will strike them with poverty. Oh, they can perhaps get money, no doubt. An insurance company can get money by peddling worry, for goodness’ sake. But money does not make us rich, and there is more than one kind of poverty.

The child in the gazebo is hopefully allowed a moment’s contemplation. It isn’t much, but it’s better than nothing, a kind of microwavable food of naturalist engagement. Contemplative effort is rather hampered now by sins of modern convenience and by the Protestant notion that meditation is solely the realm of world faith hippies and other sorts of riffraff. Never mind that Christendom records a long history of ascetics and hermits who retreated to caves and holes in the desert or by the sea to pursue Yahweh.

I have seen meditation go awry, certainly, but the antidote to this is proper meditation, not less meditation. It’s really just guided thinking, something we do most waking moments without noticing. The mind which is free to go anywhere usually goes nowhere. Far better to give the imagination a trail to wander down than to let it bushwhack through thickets of the subconscious, beleaguered as we are by snippets of television and internet droppings.

If given the chance, children might benefit from meditating on the flood that transpired over a decade ago. In 2011, the winter rains, ever more concentrated in February, bequeathed a dramatic flash flood onto Knoxville. The low-lying creek bed became an impassable torrent that forced the students to stay at school until suppertime, even though their parents were less than a hundred yards away, waiting to pick them up. Memorably, a giant green dumpster floated down Loves Creek like a strange brutalist boat and caught on the concrete bridge between the parking lot and the school. Teachers and principals were told by higher-ups not to let the kids go, since the water was over the roadway and speeding. It was a good decision. Half a foot of quick-running water can carry away an adult. A foot can move a car. Still, a few intrepid parents held on to the metal railing and made their debut as action stars to check their children out of school at a more respectable hour. Instead of fame, what they got was wet.

Meditating on this event may cultivate a number of questions. Are rains really concentrated more in February now than in decades previous? What does that mean? Is it climate change? If so, what do we do about it?

How have we managed water, historically? Have we done it better or worse than now? What could we do better regardless? Is what seems better for the roadway also better for the silt, the fish, the plantlife, and the downstream communities both human and otherwise? Who defines better? What does it mean to consider the health of silt?

Most importantly, what Harrison Ford movie did these grown people watch to make them “rescue” their children in this way? Was awesomeness gained, or did fathers get needlessly wet to the groin?

Education of this kind benefits from being outside. Beyond this one moment offered by sitting at the gazebo, the supply of educational material is nearly inexhaustible. There is the yearly rhythm of milk thistle and cicada, ironweed and aster, bluebird and wren, marcescent oak wintering, bloodroot and crocus, violet and daffodil. View the same stretch of waterway over the course of a Tennessee school year, and you will see enough to keep busy all the scientists in Yale and all the poets at Emory. The modern impetus to educate children keeps old roots in both Catholic and Protestant histories of the Western world. Watch the creek at length, and you will see the handiwork of creation’s artist. Be quiet a moment, for the stones cry out in praise. Let the tetrachromat tell of jonquil and goldfinch, and let the autistic child with perfect pitch differentiate between jaybird and mockingbird, and you will know that book knowledge is not the only knowledge. Place a map on the ground there and trace the journey of a dram of water from Colorado, to you, to Londonderry, and you will learn what the lawyer learned when he asked the Lord, “And who is my neighbor?” For it is with you that I share these waters, and we are all neighbors.

Are you familiar with the concept of watershed discipleship? This essay hints at such a concept. Center all learning (OK, not ALL) on one’s watershed and work out into the world from there. Connections, interdisciplinary work, yes! I’d like to see the rest of this.

Comments are closed.