“Where Can You Go to Grad School Without Going to Grad School?” Cat Zhang describes how The Brooklyn Institute for Social Research strives to make intellectual community available for those who don’t have time for graduate school but want to keep learning: “‘At our core is the conviction that the idea that people are anti-intellectual is false,’ Ajay Singh Chaudhary, the institute’s executive director, said. ‘The idea that people don’t want to critically engage, that they just want five-minute sound bites, is false.’”

“Technological Stagnation Is a Choice.” Jon Askonas’s lively review of Invention and Innovation: A Brief History of Hype and Failure by Vaclav Smil foregrounds the importance of carefully discerning between real limits and arbitrary ones. He also reminds us that technology’s hypers and alarmists often have much in common: “Smil’s book admits of radically different interpretations. Smil begins from the notion that we live in a world beset by innovation hype and that a healthy dose of realism is just what the doctor ordered. But is innovation hype really the dominant tendency today? What is the meaning of the stories Smil recounts if you presume instead that a lack of concern for innovation and growth characterizes our society? Smil’s book was highly persuasive for me, though not in the way he might expect; I began sympathizing with his position and finished the book vehemently rejecting it.”

“Finding a Moral Center in This Era of War.” David Marchese talks with Phil Klay about war, suffering, and God. U.S. foreign policy discussions would be much improved if they always began with Klay’s clear-eyed sense of the horrors of war: “In war, there’s a primary experience: a terrified father in Gaza as bombs are falling, unsure of whether he can protect his family; or the Israeli soldier trying to deal with Hamas’s tunnel network. There is a responsibility when you’re thinking these things through to sit with some of those primary experiences to the extent that you can, and think about them without immediately seeking to churn them into something politically useful. Because they mean more than whatever policy cash-out we get from them.”

“Who Can Repair the World?” Nadya Williams probes the redemptive vision of Eugene Vodolazkin’s imaginative narratives: “When considering people’s agency and ability to fix this broken world, Vodolazkin implies time and time again that people cannot fix broken things; only God can and will. This belief in divine intervention gives Vodolazkin’s novels a striking tinge of hope that is absent in the writings of his contemporaries.”

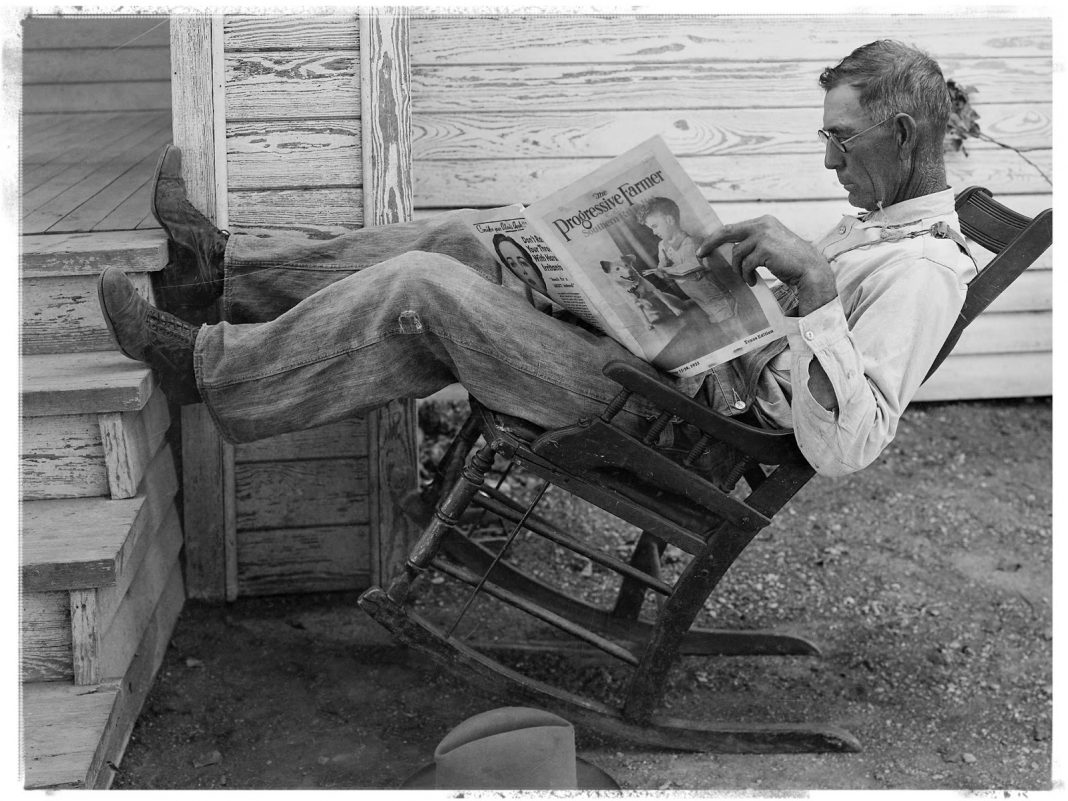

“Forming Imaginations that Value Faithful Service.” I consider how reading good novels might counteract the false standards of success that can creep into church life: “Robinson’s Gilead novels are excellent antidotes to the infectious notion of church-as-business. Another place to turn would be the novels and short stories of the Kentucky farmer Wendell Berry. These narratives likewise offer an imaginative vision that measures a ministry’s success not by attendance metrics or Instagram likes but by fidelity.”

“Sports Illustrated Published Articles by Fake, AI-Generated Writers.” AI-generated news stories may be the future, but it doesn’t seem to be the present. Maggie Harrison summarizes how some companies try to churn out cheap content and hide its origins: “Now that it’s under the management of The Arena Group, parts of [Sports Illustrated] seem to have devolved into a Potemkin Village in which phony writers are cooked up out of thin air, outfitted with equally bogus biographies and expertise to win readers’ trust, and used to pump out AI-generated buying guides that are monetized by affiliate links to products that provide a financial kickback when readers click them. Making the whole thing even more dubious, these AI-generated personas are periodically scrubbed from existence in favor of new ones.”

“Technology in the Family Home: Add before You Subtract.” Dixie Lane gives some practical guidance on tech in the home: “Managing technology in a family context is a serious challenge. . . . Every parent will have his or her own opinion on these matters. But there is one key, frankly very uncomfortable, factor without which even the best of such ideas are sure to fail our kids: that at least in part, responsible technology use is caught, not taught. The modeling parents offer matters a great deal. And we do not always model well.”

“Life Really Is Better Without the Internet.” Chris Moody describes how shutting off the wi-fi in his family’s home changed their life rhythms: “Most people won’t—or can’t—go as far as we did. But they can set aside space in their lives uncluttered by devices, or their insatiable demand for our attention. Establishing a space beyond tech’s reach is a way of declaring independence from our unsettling reliance on technology. It reminds us that we can live and thrive without it—and happily so. Our family certainly has.”

“The Chicken Tycoons vs. the Antitrust Hawks.” H. Claire Brown explains how consolidation in the chicken industry has led to collusion and higher prices. Even so, the Justice Department has had a difficult time doing anything about the situation: “Jayson Penn, who later became the chief executive of Pilgrim’s Pride, referred to 2014 as “chicken nirvana.” In just one summer, a handful of friendly executives managed to increase prices for much of the fast-food industry thanks to an ominous PowerPoint presentation and a handful of back-channel phone calls. This was possible in part because four companies — Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Sanderson Farms (which in 2022 merged with the No. 6 producer, Wayne Farms) and Mountaire Farms — control more than half of the $50 billion in chicken raised, processed and sold annually in the United States.”

“The Tyranny of Seeing Only Power.” Brad Littlejohn cautions that Sohrab Ahmari’s Tyranny, Inc. doesn’t ground its analysis on a proper understanding of freedom and friendship: “By trading the false alternatives of neoliberalism for the false alternatives of old-school Marxism (or at least dallying with the latter), Ahmari misses a fantastic opportunity to transcend this zero-sum discourse and highlight the fundamental mistakes that both have in common: namely, an obsession with power to the exclusion of authority. For cultural conservatives tired of the stale categories of Friedman-style economic conservatism, it is high time to connect the dots between our economic and social maladies, between our alienation from our work and our alienation from ourselves.”

“This belief in divine intervention gives Vodolazkin’s novels a striking tinge of hope that is absent in the writings of his contemporaries.”

Not entirely absent. I’d say that there’s a similar “tinge of hope” in the work of Mark Helprin.

Comments are closed.