There are many books about how to be a professor. Some are data-driven and look at teaching through the lens of methods. Some involve practices, but are instead driven by virtues and character traits. Most of these books focus on classroom instruction and/or the inculcation of values. How can we demonstrate care and impart knowledge? How can we manage a classroom while leaving space for self-discovery? How can we integrate experience with education? How can we be caring adults in the lives of young people? There are very few books about being a professor that approach the topic from the student perspective. If we are willing to consider a non-traditional student and a non-traditional approach, we might find the Virgil of Dante’s Inferno to be a very good guide for college professors.

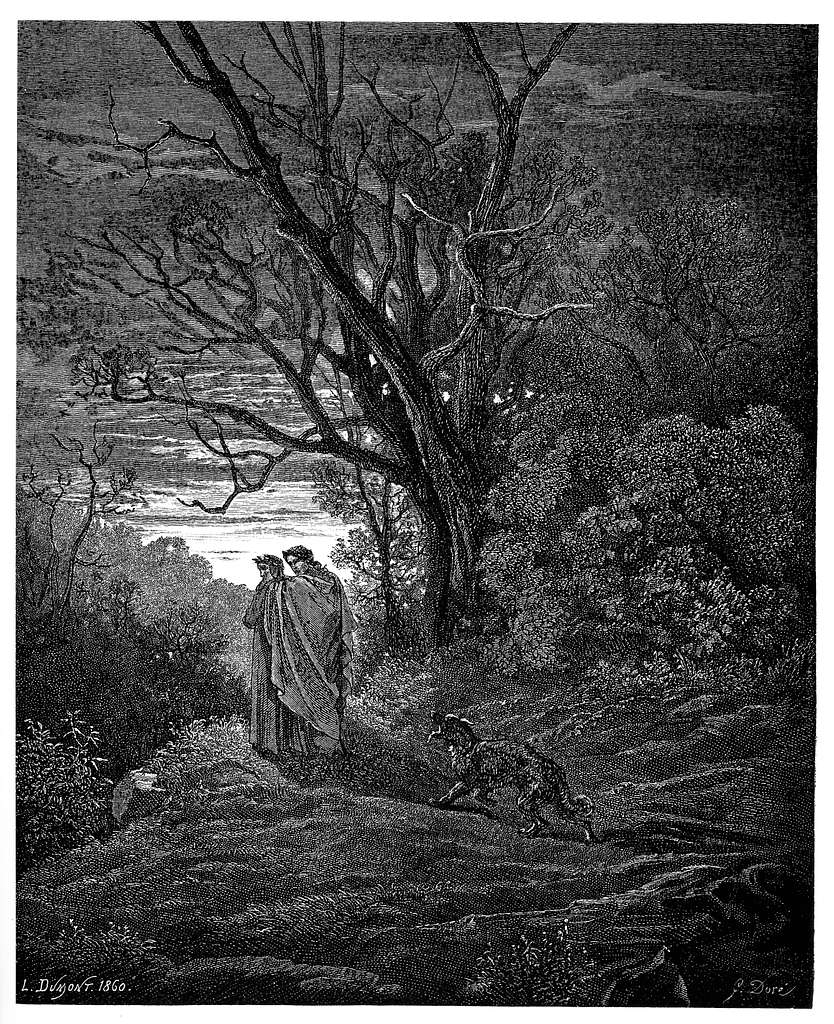

The Inferno begins in a wood, where Dante finds himself lost and confronted by a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf. He is afraid, as anyone would be. In Canto I, Dante recalls:

Midway through the journey of our life I woke to find myself in a dark wood, for I had wandered off from the straight path. How hard it is to tell what it was like, this wood of wilderness, savage and stubborn (the thought of it brings back all my old fears)

In this dramatic moment, Virgil appears, offering himself as a guide. He has been sent to take Dante through Hell and onto a better path. Dante the author chose Virgil as a guide because of his wisdom and his skill. Like a professor, Virgil was publicly recognized for his achievements. Dante says to him, “You are my teacher, the first of all my authors.” In Dante’s idealized Virgil, we can see an ideal and an example of a great instructor.

Virgil’s shade comes into Dante’s life at an important moment. Dante is in “a bitter place! Death could scarce be bitterer.” Most undergraduate students are not midway through the journey of life. But student mental health needs suggest that some are in a dark wood and some have wandered off the straight path. Such students may relate to Dante’s self-description in Canto XV:

“Up there above in the bright living life before I reached the end of all my years, I lost myself in a valley,” I replied;

Even students who do not feel this way have hard decisions ahead of them. As much fun as college can be, everything can get to be overwhelming. Students must choose a major, choose a profession—choose a life. They must square their hopes and dreams with expectations and realities.

Virgil is Dante’s “first teacher,” but in Inferno, he plays the role of a guide. He offers us an example of student-professor engagement that is not exclusively academic. He says to Dante:

And so, I think it best you follow me for your own good, and I shall be your guide and lead you out through an eternal place

Virgil responds to Dante’s crisis by taking on the role of guide for Dante’s “own good.” Virgil does this recognizing that Dante will learn from this journey and then leave him, with Beatrice. Virgil says at the very beginning, “I shall go back, leaving you in her care.” As with college professors and students, Virgil and Dante have limited time together. Dante will go on to greater things.

Dante is excited to have Virgil as his guide because he holds him in incredibly high regard. When they meet in Canto I, Dante asks if he is Virgil, “that fount from which pours forth so rich a stream of words?” He addresses Virgil as “famous sage.” In Canto VIII, Dante describes Virgil as “that vast sea of human knowledge.” Most college students do not look upon their professors with such reverential awe, but, as with Dante and Virgil, there is a clear imbalance of knowledge and experience. In the case of a college professor, there is also a significant power imbalance. One hand holds the grade book.

Virgil demonstrates how to use that power and knowledge advantage for Dante’s good. In Canto II, before they’ve gone anywhere, Dante wavers. He is unsure of his abilities. Virgil listens to Dante and suggests that his soul is “burdened with cowardice / which often weighs so heavily on man / it turns him from a noble enterprise.” Even his recognition of Dante’s cowardice includes the suggestion that Dante is capable of “noble enterprise.” Virgil then encourages Dante, calling him to be “bold and free of all your fear.” Virgil does not puff Dante up, but he recognizes his potential from the beginning.

Dante and Virgil descend into Hell together. Dante, especially initially, does not know who or what he is coming across. He does not know when to hurry and when to tarry. Virgil not only explains things to Dante, he tells him how to draw more from his experience. He teaches Dante how to ask questions of the dead. In Canto X, Dante says:

My guide, with a gentle push, encouraged me to move among the sepulchers toward him “Be sure you choose your words with care,” he said.

Virgil helps Dante recognize when to ask questions. In Canto XVI, Virgil tells him “Wait, for these are shades that merit your respect.” And in other cantos, he tells Dante when he should be listening less to the dead. Virgil is teaching all the while that he is guiding. And he is often leading Dante “with a gentle push.” Virgil is not always easy on Dante. That is appropriate. Dante is not on an easy path and has much he needs to learn.

Dante can learn from Virgil’s challenges and criticisms because he has confidence that Virgil knows what is best and will protect him. In many parts of the story, Virgil offers Dante physical reassurance and protection. In Canto III, Dante says:

Placing his hand on mine, smiling at me in such a way that I was reassured, he led me in, into those mysteries.

Virgil often makes Dante secure in very dangerous places. In Canto VI, Virgil distracts Cerberus. When Virgil offers Dante stern warnings, he also intercedes with assistance. In Canto XI, Dante is warned about the Gorgon, but he is also helped to resist her. Virgil says:

Now turn your back and cover up your eyes, for if the Gorgon comes and you should see her, there would be no returning to the world!” These were my master’s words. He turned me round and did not trust my hands to hide my eyes but placed his own on mine and kept them covered.

Virgil will even take Dante into his arms. In Canto XIX, Dante recounts:

Then he took hold of me with both his arms, and when he had me firm against his breast, he climbed back up the path he had come down. He did not tire of the weight clasped tight to him, but brought me to the top of the bridge’s arch, the one that joins the fourth bank to the fifth. And here he gently set his burden down— gently, for the ridge, so steep and rugged, would have been hard even for goats to cross. From there another valley opened to me.

Virgil takes Dante on as a personal burden. He cannot casually or inattentively guide Dante through Hell. Virgil holds Dante close, he carries him when needed, he covers his eyes. At times, Dante seems completely dependent on Virgil. In Canto VIII, a fearful Dante pleads with Virgil:

don’t leave me please,” I cried in my distress, “and if the journey onward is denied us let’s turn our footsteps back together quickly.”

Throughout the journey, Virgil continues to challenge and encourage and carry, as appropriate. From Dante’s perspective, “he did not tire of the weight.” It requires great effort from Virgil to be a good guide for Dante. And this effort took Dante to where “another valley opened to me.”

Virgil seems to be superior to Dante in so many ways, but it is clear in the Inferno that Virgil is imperfect. Even if his is the nicest neighborhood there, he essentially resides in Hell. Virgil is wise, but he is still surprised by some of the things they see together. Virgil even makes mistakes when he is with Dante. In Canto XXIII, Dante and Virgil realize that they’ve been lied to by some devils, and Virgil is angry that he was easily tricked. He does not regain his composure until Canto XXIV. But Dante loves Virgil despite his occasional errors and his imperfections. Even though Dante sees that Virgil has been fooled, Canto XXIII ends with Dante turning “to make my way behind those cherished footprints.” Virgil’s humanity does not lessen his ability to guide Dante through a challenging environment.

As they go on, Dante takes advantage of his time with that “vast sea of knowledge.” He constantly asks Virgil questions. And because his respect for Virgil is so great, Dante gets a great deal of affirmation from Virgil when he receives approval. In Canto XIX, Dante recalls proudly:

I think my master liked what I was saying, for all the while he smiled and was intent on hearing the ring of truly spoken words.

Virgil is not a flatterer, but he acknowledges Dante’s ability and achievements. Virgil is not inscrutable. He shows his pleasure with Dante. In Canto VIII, Dante refers to Virgil as “my dear guide,”

“…who more than seven times restored my confidence, and rescued me from the many dangers that blocked my going on”

Virgil’s encouragement and approval help Dante just as Virgil’s correction and protection did.

We see Dante’s own strength called out by Virgil in Canto XXIV. They have just been fooled by the group of devils and are confronted by a ruined bridge. Dante says:

just so I felt myself lose heart to see my master’s face wearing a troubled look, and as quickly came the salve to heal my sore: for when we reached the shattered heap of bridge, my leader turned to me with that sweet look of warmth I first saw at the mountain’s foot. He opened up his arms (but not before he had carefully studied how the ruins lay and found some sort of plan) to pick me up. Like one who works and thinks things out ahead, always ready for the next move he will make, so, while he raised me up toward one great rock, he had already singled out another, saying, “Now get a grip on that rock there, but test it first to see it holds your weight.”

Virgil does not hide his troubled look, but he also looks for a solution. Virgil picks Dante up, but he does not carry him through the entire climb. He teaches Dante to climb. When Dante is tired and exhausted, Virgil commands him:

Stand up! Dominate this weariness of yours with the strength of soul that wins in every battle if it does not sink beneath the body’s weight. Much steeper stairs than these we’ll have to climb; we have not seen enough of sinners yet! If you understand me, act, learn from my words.” At this I stood up straight and made it seem I had more breath than I began to breathe, and said: “Move on, for I am strong and ready.” We climbed and made our way along the bridge, which was jagged, tight and difficult to cross, and steep—far more than any we had climbed.

The Inferno’s narrative account of Virgil and Dante traveling through Hell is a good portrayal of an excellent educator. Virgil understands his role as guide and takes it on consciously and seriously. He is encouraging but not easy. He challenges Dante and does not always hold his hand. But he does hold his hand when needed. Virgil cares about Dante, cares enough to carry him when that is the best way to protect him. Virgil is caring, but he is qualified because he has genuine knowledge to impart. Virgil exposes Dante to hard things, but he doesn’t abandon him with demons. Dante gains his own wisdom along the journey, and Virgil is happy to affirm him and send him on to bigger and better things. Virgil is willing to be left behind.

Dante will not just emerge from Hell having seen some things. He will emerge from Hell with more wisdom and strength of his own. By the end of Inferno, Dante achieves nearly all the desirable non-academic learning outcomes for an undergraduate student. He undertakes a journey and learns at every stop along the way. He studies his surroundings, he turns to his guide for knowledge, he is unceasing in his inquiry. He learns more about his world but also more about himself. His journey is not on the surface of things, and it contains real challenges. He wrestles with serious matters and moments.

Dante’s experience of Virgil as a guide can be summed up by what he relates in Canto XIX, after being carried: “another valley opened to me.” This is what we want for our students, too. Students sometimes come to us in crisis, but always they come from a world filled with challenges and are with us only for a season. We could do far worse as professors than to model our approach to education and guidance on Dante’s Virgil and walk with our students until another valley opens to them.

Image credit: Gustave Doré

Thanks for this wonderful essay. I tried to be a school teacher for 25 years. Not only do I think I was not very good at it but I am aware that I was in constant disagreement with the administration of the system, from top to bottom.

Can you find a Virgil for administrators and bureaucrats and write something as good for them?

again thanks, Ray Stevens

Comments are closed.