One of our most anticipated harvests of the year is also the first.

In early spring, usually late February or early March when the snow begins to melt, we gather our supplies and bundle up the kids and trek into the woods to tap our maple trees. Our littlest (there’s always a littlest) rides with the buckets in the sled that his older brother is pulling.

Together we tromp from tree to tree with taps and tubes and hammer and drill. After giving the annual demonstration, each of our children takes turns drilling a hole, placing a tap, and eagerly watching for sap to appear. And then, naturally, they dip their heads under the tap to catch those first drops of sweet water—pure maple sap, straight from the tree.

It’s always a joyous occasion for our family, one that we have shared with many others in the years since we’ve lived here. After the sap is boiled down and ladled into jars, it will sit in our pantry for most of the year—an abundant and free source of sugar, direct from the land.

But all of this abundance comes with responsibility. It takes, on average, forty years for a maple sapling to reach maturity and be ready to tap. The trees we are harvesting from today were planted, or seeded, decades before we moved here. And we wouldn’t want to do anything to damage the trees or otherwise diminish their potential for the generations that follow. We’re not alone in that regard. The most common question we are asked at our maple syruping workshops is, “Does it harm the tree?”

There is an innate desire inside all of us (call it a conscience) that wants to protect the source of our sustenance. We are careful to choose a large enough tree, not to place too many taps, and not to tap in the same place as last year. After all, sap is the lifeblood of the tree—what it needs to furnish its limbs and leaves and seeds with vital nutrients. A properly maintained sugar bush will provide sweet sustenance for centuries—perhaps indefinitely.

This is the natural stewardship of syruping; the trees must be tended. Every producer—even the giant commercial outfits—must approach each tree on the tree’s own terms. As sugarmakers we submit to the natural limitations of maturity, climate, geography, and season. The tree will give of its surplus, but only if properly cared for. It is, perhaps, the last wild harvest in our otherwise industrially dominated food system.

But it appears that this kind of stewardship, and the life it engenders, is about to change.

‘Radical ideas’

“Scientists at a research lab deep in the maple woods of northern Vermont have made a discovery that could revolutionize New England’s most tradition-steeped form of agriculture,” reports the Boston Globe. “But their work may also threaten a cherished way of life.”

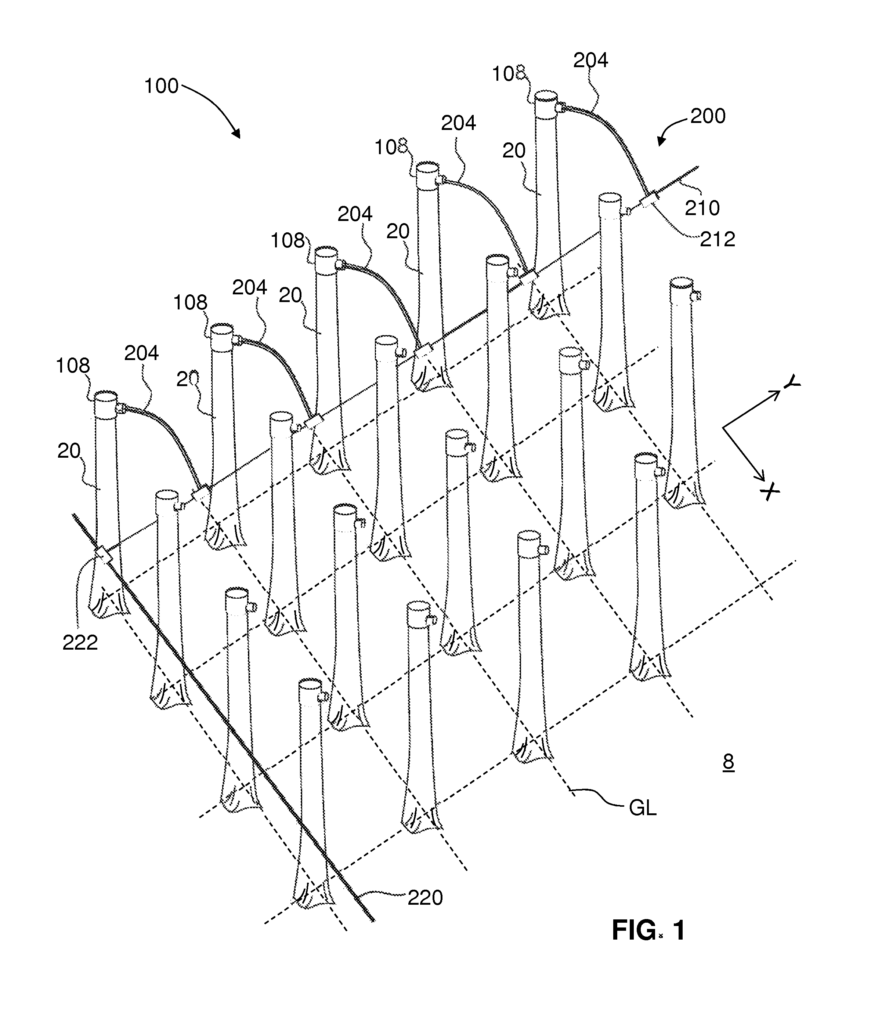

Researchers at the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center have discovered that maple sap can be “efficiently vacuumed from the decapitated trunks of saplings.” Using a mess of tubes and fittings and pumps on a scale that can only compared to dystopian science fiction, the future of maple syruping may now entail cutting the crowns off of healthy maples, affixing spigots, and forcibly sucking sap directly from the remaining stump.

“We discovered that vacuum-induced flow makes the upper tree unnecessary for sap production,” the inventor said. A “significant amount of sap” can be collected by forcing groundwater through the root system and up the trunk of the biological scaffolding. “Like straws.”

It’s a “radical idea,” the Globe admits, but “radical ideas . . . have a way of becoming reality if they make money.”

A forest dethroned

Following this innovation to its logical conclusion, inventors identify one of the main benefits to be massively scaling up production in a limited space. In other words, to factory farm sugar maples like we do everything else. According to the University of Vermont’s patent filing, “the plantation method” would permit as many as 10,000 saplings to be grown on a single acre—as compared with the 40 to 80 mature maples you might find in a natural forest. Spared of their “unnecessary” crowns, densely-packed saplings could produce as much as 400 gallons of syrup per acre as opposed to 40 gallons using traditional methods.

The “plantation method” promises to significantly boost yields in far less time, and it’s likely to become the industry standard, (though at this point no manufacturer has chosen to produce the necessary equipment.). Such technologies raise an underlying question: If a maple farm becomes a plantation, what does that make the trees?

“It could economically benefit the industry,” says a major producer in Vermont. “But it may force maple production out of the woods and into tidy farm rows, like any agribusiness. And that’s sad.”

If moving the trees out of the forest wasn’t sad enough, the patent filing also describes “erecting walls or a roof” over maple plantations to control temperature, pests, and all those other pesky limitations that nature imposes on human ambition. Take, for example, the short harvest season. A typical sap-collecting period lasts three to six weeks. Sometimes eight weeks with a late frost. But inside of climate-controlled warehouses, perfect freeze-thaw temperatures could be artificially maintained year-round, with trees being pumped continuously until their useful end is achieved.

‘It’s just wrong.’

Reaction from the sugarmaking community has been mixed. Some can see the benefits of turning marginal land into economically productive tracts. Others are saddened by the prospect of generational traditions going the way of the factory farm.

“Cutting off trees to get sap. It’s just wrong,” wrote one producer in an online forum devoted to the maple industry. “This new method really destroys the ethical reputation of making maple syrup and being good stewards of nature that we all enjoy striving for.”

But nearly all see the inevitability of it. Now that the opportunity exists, with patents granted and commercialization underway, most foresee the end of the traditional maple farm. This genie (or should I say syrup?) isn’t going back in the bottle.

What of the trees? Deprived of their limbs and leaves they’ll die, of course. But only after having been drained of their sugary crop for several years. When they reach the end of their useful (i.e., “productive”) lives, the trees can be conveniently discarded or replaced. Just like people.

What do we owe creation?

It all feels like a familiar recurrence with man: A chance discovery, a nomad wandering in the woods, fortuitously finds sweet water dripping from a broken limb. Boiling the water makes it even sweeter. The man enjoys his newfound bounty and shares it with his neighbors. They marvel at the forest’s sustenance, the beauty of its autumnal blaze. There is reverence for the created order and for its Creator. There is gratitude for gifts freely given and wonder for the miracle of it all. Seasonal harvests give rise to annual celebrations that bring neighbors together. This may go on for generations. Until one day a “market” is discovered. From that point on, the marvel becomes a commodity, more attractive to sell than to share. The man expands his production far beyond the requirements of his own family and community. He “scales up,” acquiring more land, more taps, more technology. His attention turns to “efficient methods of production” and “labor-saving devices.” Until one day, relieved of his reverence, he realizes that he doesn’t need the tree at all. He can save a tremendous amount of labor by simply cutting the tree in half and pumping out the sap. The kingly spires robed in silver, wreathed in gold, are reduced to sputtering stumps of a forest, decrowned of its canopy and dethroned of its wonder.

“To live,” writes Wendell Berry in Art of the Commonplace, “we must daily break the body and shed the blood of Creation. When we do this knowingly, lovingly, skillfully, reverently, it is a sacrament. When we do it ignorantly, greedily, clumsily, destructively, it is a desecration. In such desecration we condemn ourselves to spiritual and moral loneliness, and others to want.”

What do we owe creation? This is a question only stewards ask. Do we treat the created order as if it belongs to God or exclusively to ourselves? Is dominion the same as domination? Is stewardship the same as subjugation? Such notions need to be worked through. Such notions have a profound impact on how we see and treat the world around us. And the people around us.

“The righteous will inherit the land,” the psalmist writes. Five times in the same psalm, he writes it. The wicked will be “cut off,” he says. “Like smoke they shall vanish.” When the land reverts to the righteous, and I have it on Good Authority that it will, it will revert to those who revere both their Creator and His creation. Those who steward without subjugating. Who shed the blood and break the body knowingly and lovingly. And who never lose their sense of wonder for the miracle of it all.

“For you shall go out with joy, and be led out with peace; the mountains and the hills shall break forth into singing before you, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands.” (Isaiah 55:12)

Image Credit: The Grovestead (used with permission)

All your links are 9 or 10 years old. Has anything come of this research? It doesn’t look very viable to me, if you can only do it for a very short time before the saplings die, and of course it’s totally irrelevant to families like mine just making enough for ourselves for a year and having a good excuse to stand around a fire for a few weekend days every winter.

An update: https://www.themaplenews.com/story/whatever-happened-to-the-sap-cap-experiment/497/

Comments are closed.