“A blue child’s jacket, men’s black Nike shoes, a silver thermal blanket,

and a jumble of clothing caught in the razor wire remain

as a reminder of the hordes of foreigners from around the world

who entered Texas just a few weeks ago.”

This word picture appears in an article titled “Inside the Brewing Fed-State Showdown at the Texas Border.” The federal and state governments do indeed find themselves at odds over barbed wire and border crossings, yet those events play themselves out in some town I’ve never heard of before this article appeared on my screen. Who is right and what should be done are things people searching for power try to explain, promising, of course, that they are the only ones who have the answers.

This has been the cycle for ten years now, ten years since the last legislation on immigration actually passed congress. Why so? Perhaps the answer hides in the way we speak, how we narrate these events.

Language matters. When we find ourselves distressed, our minds race with self-critical language, and we become the words we speak over ourselves. We try to cure this by introducing positive thoughts about ourselves, but a hateful, shameful thought is much harder to eradicate than a kind one is to introduce. How much more does this effect play out in the words we use to describe other people?

The saying, “If you don’t have anything kind to say, don’t say anything at all,” could include the words we speak and those we let sit in the high places of our mind. Our mouths may be silent, but instead of seeing a faulty human being who is under great stress, we see a person worthy of words we would never utter around our grandmothers. They become othered, and we no longer feel bad when we take out our own stress on them.

Language matters all the more when we speak of people, especially the people furthest from our daily lives. In a hurried and distracted world, people, all too quickly, become no more than words.

“Illegal immigrants.”

“Illegal aliens.”

“Hordes of foreigners.”

These words are well weathered in the media cycles. They elicit images of brown people crossing stretches of dessert, swimming the Rio Grande, or getting caught for smuggling in the fentanyl which killed yet another suburban teen.

These words are mere words, easily batted around as they only represent the vague feelings of “otherness” presented by these seeming “invaders.” “Hordes of foreigners” don’t register as people, just as the boogie man is not a person–it is always easier to fear an idea than a face with a story.

Yet the rest of the word picture in the article I read began to conjure up such faces and stories.

“a blue child’s jacket.”

“men’s black Nike shoes.”

“a silver thermal jacket.”

In the winter, children in blue jackets abound in the parks down the street from my home, trying to keep warm as they climb over the jungle gym. I myself use a blue jacket on evening walks.

A friend of mine loves to run and does so in his black Nikes almost every day (except Wednesdays, when he sleeps in). I wave to him if I see him on my way to work.

And a thermal jacket? One has kept me from freezing a time or two on mountain camping trips. Does this “jumble of clothing caught in the razor wire” constitute the vicious or alien items by which we name the people crossing the border?

These items could belong to any of us. We might find them safely in our closet and not blowing in the dry, south Texas wind.

This sense of commonality and the felt obligations it entails may be part of what that first-century Jewish Rabbi had in mind when he told a story to a man who wanted to know who his neighbor was. Even in a digital and busy age, that word’s meaning can still be experienced in many—albeit scattered—pockets of our country. Families still make meals for others recovering from surgery. Children from neighboring homes form unlikely friendships. Young couples volunteer to check in on their elderly neighbors, whose own family might live far away.

Yet to be a “neighbor,” this rabbi told his interlocutor, is not to live a house down from another. To be a neighbor meant taking an active interest in the wellbeing of those whose need confronts us, whose need we might be able to meet, even if this needy neighbor belongs to a group of people we fear or despise.

It’s true that we have overlapping loyalties to many different communities: local, state, national, global. When a new park opens or a beloved restaurant closes, we are reminded of our local community’s needs and opportunities. Elections and history class attempt to remind us of our state and national loyalties. Changes to climate and wars remind us we all share the same earth–and the same fate. Yet as the scale of our loyalties increases, we can all too easily forget the human lives caught up in these distant events that scroll across our screens. And if we become caught up in the pitched ideological battles that play out on global or national scales, we may neglect our responsibilities to those close at hand.

It is this interdependence which draws my eyes to Shelby Park in Eagle Pass, Texas. The political rhetoric on our screens will end up affecting the immigrants in my community–my friends, those who work at the local grocery store, the families I see playing in the parks. The national conversation is a thousand miles away from you and me, but our next conversation is not a thousand miles away—it is right in front of us. So, too, is our neighbor.

Who is your neighbor?

Who could become your neighbor?

Love does not live a thousand miles away. As worthy as it can seem to dedicate oneself to the great issues facing our nation, powers are at play which are far beyond our control. In these movements, we are but a speck of dust in the great desert. But here, where our feet are, we hold a power forgotten. Movements and national discussions have their place, but they should not lead us to forget our obligations to our neighbors.

So long as there are politics, there will be “others,” groups of people to fear and blame. The words we use to describe these people will define whether or not we see them as aliens or neighbors. Yet, no matter what we name these groups, their members will continue to share our communities. We’ll wear the same jackets and shoes, breathe the same air, share the same aspirations and worries. We need a language, a way of seeing our world, that does justice to this shared reality.

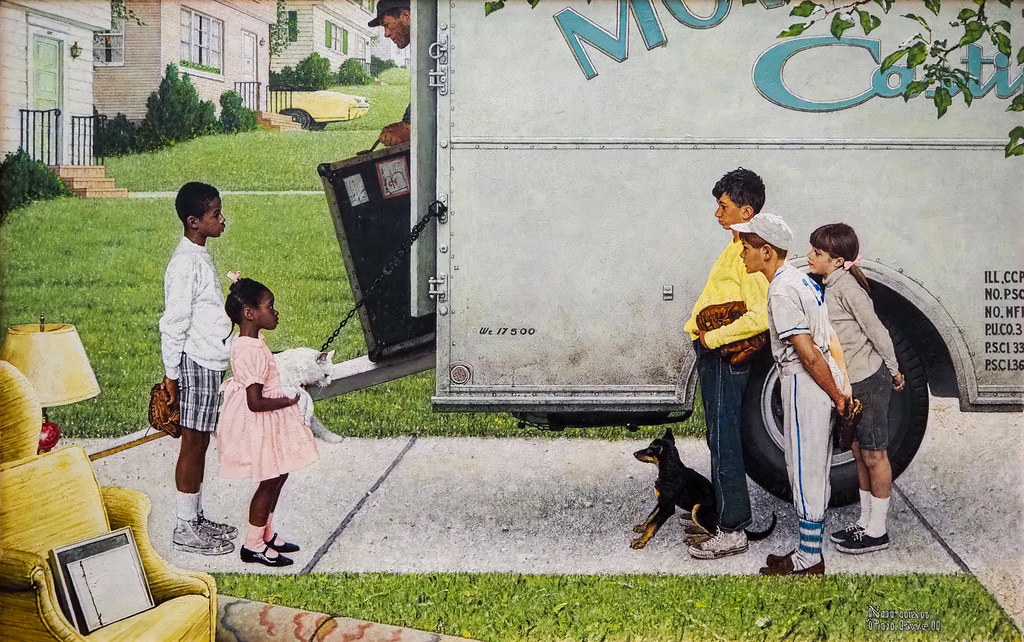

Image Credit: Norman Rockwell, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) via Flikr

You are completely right. Words have power. Names having special power is an ancient and universally acknowledge fact–“It is stated that knowing someone’s, or something’s, true name therefore gives the person (who knows the true name) power over them” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/True_name)

Here are some names that knowing will give you power:

Laken Riley. Say her name.

Jeremy Poou Caceres. Say his name.

Shannon Patricia Jungwirth. Say her name.

Jorge Alexander Reyes-Jungwirth. Say his name.

Alberto Trejo Estrada. Say his name.

Melissa Powell. Say her name.

Riordan Powell. Say her name.

Catalina Valdez Andrade. Say her name.

Merced Andrade Ballon. Say her name.

Aiden Clark. Say his name.

Sandra Vazquez Ceja. Say her name.

Omar Gallegos Vazquez. Say his name.

Terry Aultman. Say his name.

Brenda Aultman. Say her name.

There are countless more names to know.

“We need a language, a way of seeing our world, that does justice to this shared reality.”

Indeed. A good start would be to stop othering our poor and working class neighbors as hard-hearted racists when they complain about the costs they’re bearing for the policies of openness that lead to finding sneakers and coats on razor wire at the border. In my part of the country it’s the poorest who are worst affected and most angry (and many of them, too, have brown faces and wear blue jackets and black Nikes) as their schools and medical facilities become overwhelmed, increasing demand for cheap housing continually pushes up their rents, they have even more trouble finding work, and find themselves prioritized behind newcomers by social and charitable services.

And then they’re called racists and admonished to practice Christian charity and like it by their betters who pay no real cost but who get to feel morally superior and/or are profiting from the situation.

That first century rabbi had plenty to say about these kind of people as well.

That was kind of my thought as well reading the piece. There’s a strong whiff of Rob Henderson’s “luxury beliefs” here. So kudos to you. The only productive work on the internet right now is breaking the intellectual and narrative frames that blinker us in the laptop class as you’re doing in this comment.

Comments are closed.