“This was the greatest disappointment and disaster in my life,” wrote Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower in 1967, two years before his death, “the one I have never been able to forget completely. Today when I think of it, even now as I write about it, the terrible keenness of our loss comes back to me as fresh and terrible as it was in that long dark day soon after Christmas, 1920.”

Forty-seven years had not dimmed the pain of losing a child. Eisenhower and his wife, Mamie, enjoyed a rich relationship filled with impressive accomplishments. What meaning they found in life, they said, ended and began anew that long-ago December.

Their first son, Doud Dwight, took ill just before Christmas in 1920. A new maid had recently recovered from scarlet fever and still carried the bacteria. The three-year-old boy, known as “little Ike,” a nickname ultimately shortened to Ikey then Ikky and Icky, contracted the disease and was quarantined. It turned to meningitis.

“I haunted the halls of the hospital,” Eisenhower recalled. “The doctors did not allow me into the room. But there was a porch on which I was allowed to sit and I could look into the room and wave to him. Occasionally, they would let me come to the door just to speak to Ikey. . . . Hour after hour, Mamie and I could only hope and pray.”

Ikey lasted ten days. He died in his father’s arms on January 2, 1921. That particular moment was to remain taboo in conversation for the rest of Eisenhower’s life. “We never talked about it,” Mamie told her granddaughter. “I never asked him because it was something that hurt so badly.”

In this Mamie displayed prescient wisdom. Since the 1990s, top therapists across the globe have confirmed that our popular perception of grief work may be unhelpful and inaccurate. “Does ‘grief work’ work?,” asked three of the world’s leading grief researchers, Wolfgang Stroebe, Margaret Stroebe, and Henk Schut. Their answers were surprising and changed the course of 21st-century therapy.

They observed that in the current way of thinking, “we must confront and speak of our feelings and reactions to the death of a loved one. But what evidence do we have that this is so?” Not much, they discovered. The Stroebes and Schut learned that there was no measurable difference in depression between those who worked through their grief and those who did not. “Grief work,” the respected experts concluded, “is not always as essential for adjustment to bereavement as theorists and clinicians have claimed.”

Two other renowned experts, Terry Martin and Kenneth Doka, maintain that we as a society are wrong to hold to the traditional view that sharing emotions is the only mark of healthy grieving. “Another, equally sound pattern . . . tends to be private,” they write, suggesting that in silence many mourners, particularly men, find the solace and meaning they seek. “We must respect individual needs and differences,” Martin and Doka observe.

Guilt over Ikey’s death did not debilitate the Eisenhowers, but it took a heavy toll.

Mamie was not present when her son passed. She was battling a cold so severe there was concern of pneumonia. She never forgave herself for failing to be there.

Eisenhower also felt the burden of remorse. He brooded for years over time missed with his son due to the demands of military life. “I have never known such a blow,” he wrote in 1967. “I didn’t know what to do. I blamed myself because I had often taken his presence for granted.”

Eisenhower and Mamie also felt guilt for hiring the maid and for trusting the Army doctors, who were ill-equipped at that time to deal with children’s diseases.

Such feelings are nearly universal among bereaved parents. Self-recrimination often leads to a sense of shame and guilt. Mourners report revisiting the death in their minds and the roles they played in helping, or failing to help, their child. Parents often feel that they were inadequate protectors and providers, according to grief experts Margaret Miles and Alice Demi, and condemn themselves for having survived.

Thirty years later Eisenhower confided to his friend John Gunther that he was “on the ragged edges of a breakdown” for months after his son’s passing. Stephen Ambrose, who held numerous conversations with Eisenhower while editing the general’s military papers, observed: “He found it difficult to concentrate for a long time after Icky’s death or get interested in anything. He did his job without enthusiasm.” Biographer Kevin McCann noted something similar. “Talking to him about that saddest of events in later years, I got the clear impression that he was in a very bad way emotionally for a time.”

Mamie would refer to the boy now and then, as many bereaved parents do. But her husband tended to keep the pain to himself, according to Reverend MacAskill of the Gettysburg Presbyterian Church, where the Eisenhowers were members during their retirement years. For both parents, the shadow of their son’s death never completely lifted.

Researchers have found that the loss of a child significantly shapes and alters the worldview of bereaved parents. This was true with the Eisenhowers. “The loss of his first son changed Ike’s character,” wrote McCann.

Mamie also saw this difference in her husband. “For a long time, it was as if a shining light had gone out of Ike’s life,” she said. “Throughout all the years that followed, the memory of those bleak days was a deep inner pain that never seemed to diminish.” Decades afterward, she told family friends, “That sad, sad event had a lasting effect on the General.”

Ikey’s death affected the couple in other ways. Bereaved parents relate that their most devastating challenge is the relentless loneliness they feel. One study of fifty-two parents who had lost a child to an unexpected death by illness, such as the meningitis that took Ikey, found that grief and loneliness tend to rise over time.

Eisenhower and Mamie’s relationship remained solid, though troubled. “Half a century later,” wrote Julie Nixon Eisenhower, “Mamie was still unwilling to say much about how Ikey’s death changed her relationship with Ike. The pain is too deep. But there is no doubt the loss of their beloved son closed a chapter in the marriage. It could never again be unblemished first love.”

This observation is not quite as forbidding as it may seem. Unblemished first love may pass as trust, appreciation, acceptance and understanding mature. The chapter of their early years and their first son being with them was closed by Ikey’s death. But it did not end their marriage or their lives.

The couple’s second son, John, was born on August 3, 1922. Eisenhower had been given three weeks leave. They welcomed the child as a blessing. “John did much to fill the gap that we felt so poignantly and so deeply every day of our lives since the death of our first son,” Eisenhower wrote. “While his arrival did not, of course, eliminate the grief we still felt, he was precious in his own right and he did much to take our minds off the tragedy. Living in the present with a healthy, bouncing baby boy can take parents’ minds off almost anything.”

In the winter of 1922 Eisenhower was ordered to Panama. They were moving to an exotic locale after months of constant reminders of Ikey. The new surroundings did not alter their grief in any way, but Panama provided the first steps into their future without him.

Over the years, Eisenhower and Mamie honored Ikey’s memory in their own ways. “John is the only son I have,” Mamie said years later. “That’s the way I’ve thought of it after Icky.” This method of coping carried its own challenges for the grieving mother. “It took me many years to get over my ‘smother love’,” Mamie related later. “It wasn’t until Johnny had children of his own that I was able to stop.” Yet she continued to fuss over her husband’s health and safety well into his presidency and after.

Eisenhower dealt with Ikey’s death differently.

“Only once did Ike ever talk about his first son,” wrote Maxwell Rabb, secretary to the Eisenhower Cabinet from 1953 to 1958. “‘That was a very difficult moment for us,’ he said, passing over it very quickly. I think his silence on the subject is significant.” Eisenhower may not have mentioned Ikey to his colleagues in the White House, but the boy was never far from his mind.

Yellow had been Ikey’s favorite color. Ann Thomas, who served as Ike’s secretary during his presidency, from 1953 to 1961, recalled: “I came into the Oval Office one day and found him staring off into space. He turned to me and said, very simply, that he was thinking of the little boy. Upstairs, in the family living quarters, there would always be fresh flowers. Once he pointed to some—I can’t remember what kind it was—and said: ‘Icky always liked those flowers.’ Imagine, remembering a detail like that.”

Eisenhower and Mamie walked through the valley of grief together. Their relationship was rewarding, despite and perhaps in some ways because of Ikey’s passing. They came to value the transience of life and found meaning along the dark path of loss they shared.

For the rest of his life, Eisenhower sent Mamie yellow roses on Ikey’s birthday.

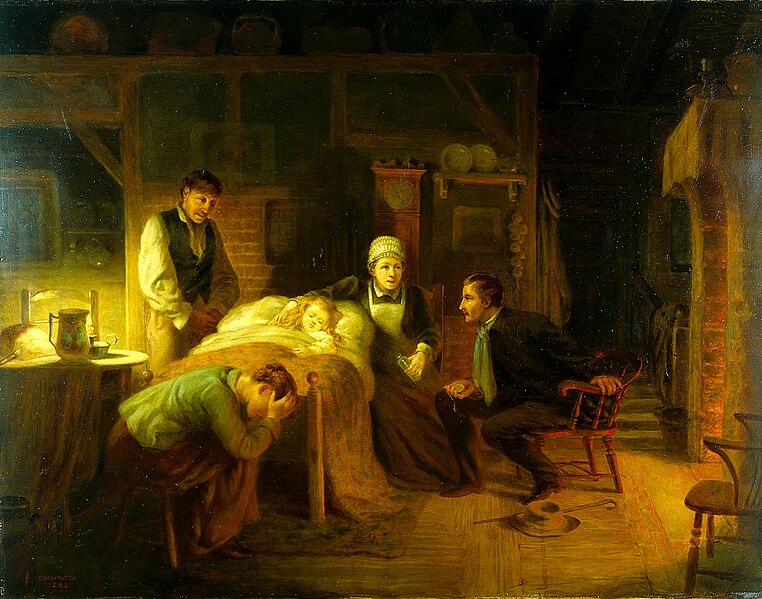

Image Credit: John Whitehead Walton, “Anxious Moments: a sick child, its grieving parents, a nursemaid and a medical practitioner” (1894) via Wikimedia

So moving. I did not know he had lost a child. My only niece was killed in a car accident at 20. We lost, not just her, but her future family. The shock and disbelief lasts for a long time.

Thank you for publishing this piece. I wept all the way through it, for Ike and Mamie, but mostly because it made me remember the loss of my wife nine years ago. I have missed her most hours of every day since she left. I wept for her, I wept for me, I wept for the Eisenhowers, and somewhere in the back of all this, I was weeping for the loss of decency and decorum we have suffered in these last decades.

I didn’t know about this loss and found that the way you wrote about it was very touching. Thank you for sharing it.

Comments are closed.