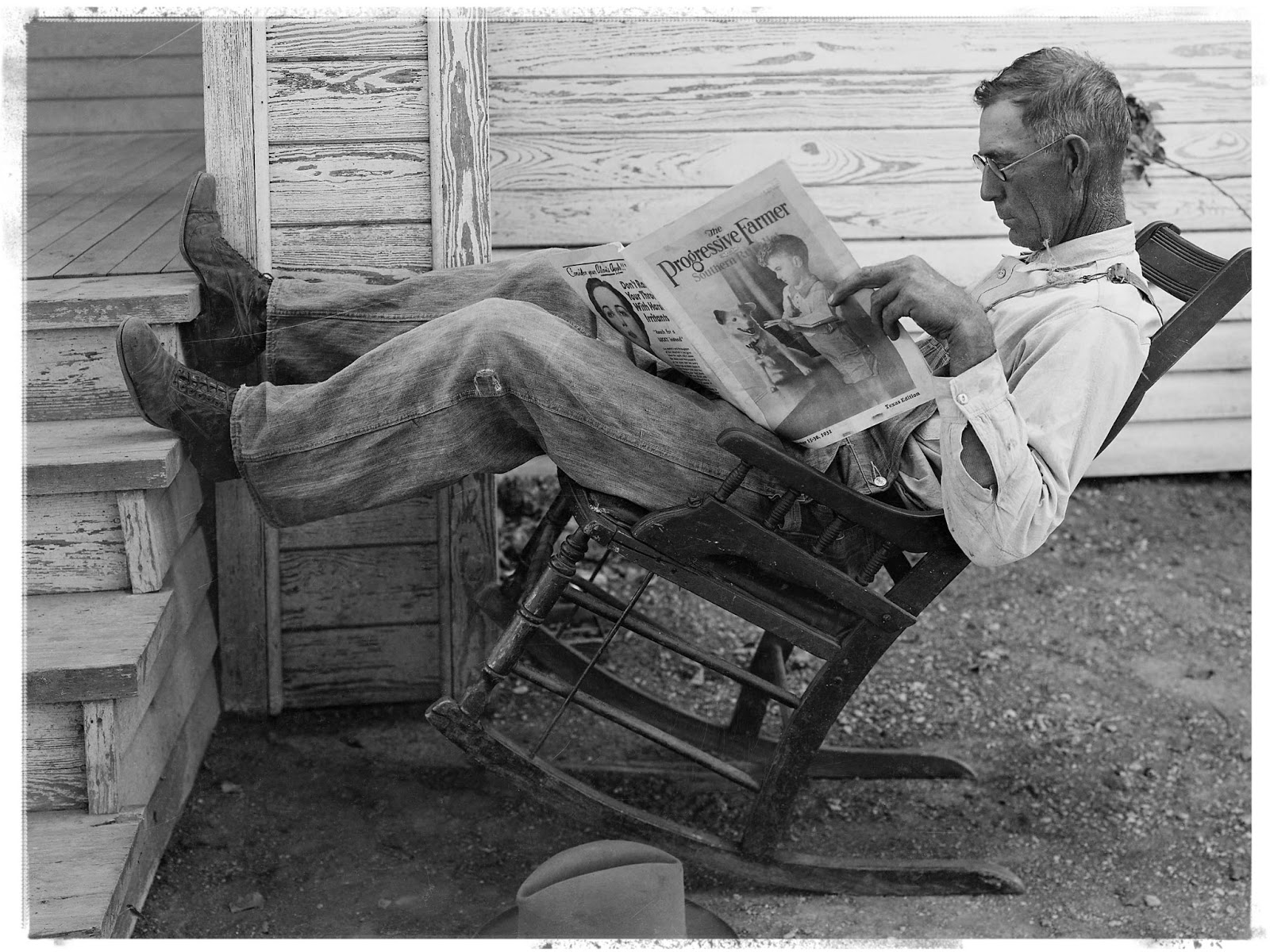

“In ‘Barons,’ Austin Frerick Takes on the Most Powerful Families in the Food System.” Twilight Greenaway interviews Frerick on the depressing stories of corporate power and government capitulation that his recent book chronicles: “What I call the “Wall Street Farm Bill” . . . is designed specifically to incentivize overproduction of grain. If you grow carrots, you don’t really get anything. The dark joke I keep telling after writing this book is that the only farmer really on the free market is the CSA vegetable farmer.”

“Place and the Nation.” John G. Grove draws on Roger Scruton’s place-based understanding of a nation to critique the contemporary national-conservate movement: “Scruton’s understanding of the nation thus emerges largely as a pre-political loyalty—not to family, tribe, or people who are “like us,” but to the people who live in and are committed to a particular place.”

“Power Down.” Rory and Becca Groves describe their experience shutting off the power for a week, and they invite others to join them: “We’ve repeated the experiment several times since and each time found it to be profoundly fulfilling, grounding, and family-bonding. Powering down has a way of recentering and refocusing our busy, distracted, lives in a way no other activity can, which is why we keep returning to it year after year.”

“The War at Stanford.” Theo Baker, a student at Stanford, discusses how the Hamas attacks and the ensuing war in Gaza have fractured the campus community and eroded nuance and careful thinking: “Many young people have come to feel that being angry is enough to foment change. Furious at the world’s injustices and desperate for a simple way to express that fury, they don’t seem interested in any form of engagement more nuanced than backing a pure protagonist and denouncing an evil enemy. They don’t, always, seem that concerned with the truth.”

“A Conservative Thought Experiment on a Liberal College Campus.” Rachel Slade recounts her experience sitting in on one of Eitan Hersh’s classes last fall as he walked students through American conservatism and helped them think through the events of October 7: “His students confided in him that while inside his classroom, they felt freer to talk about contentious issues than anywhere else. By introducing a refreshingly contrary perspective, in this case conservative thought, Hersh believes he is somehow taking a lot of the emotional heft out of America’s most gut-wrenching topics and forcing students to find new intellectual muscles to process the right-leaning take.”

“Mutual Endangerment Society.” Leah Libresco Sargeant pens a thoughtful essay on how to disagree fruitfully. You might consider this a primer to begin preparing for our fall conference on civility and its limits: “in the long term, and where there’s a relationship to sustain the work, it makes sense to offer a different kind of retreat. Not the careful separation of a demilitarized zone—I won’t ask for you to be fired for being wrong if you don’t ask for me to be fired—but the open door of an invitation to conversion. We are striving not to mutually tolerate each other’s errors but to create strong relationships of trust that allow us to adversarially collaborate in pursuit of truth.”

“Ordinary Time.” Elizabeth Corey wonders if ordinary, quotidian life can be the subject of good writing: “Some of the freshest writing right now comes from outlets like Public Discourse, Plough, Local Culture, The Hedgehog Review, and Comment, where writers consider topics that haven’t always been given their due: nature, music, disability, marriage and dating, the lives of children, friendship, even food and farming. Not that anyone should cease writing about religion, politics, and war: but it is worth noting that this well-worn triumvirate does not exhaust human experience.”

“Divine Dance.” If you’re near Greensboro, North Carolina, stop by and say hello when I’m in town two weeks from now.

“My Biggest Regrets.” Bill Kauffman reflects on missed opportunities: “The coach, who had a volatile gene, barked, ‘Kauffman!’ I jumped to attention. He grabbed me by the jersey. ‘Can you guarantee me a successful suicide squeeze?’ (Laying down a bunt was one of my few undisputed talents.) ‘Well, there are no guarantees in life,’ I replied, smart-alecky. He pushed me back toward the bench. The batter struck out. It’s funny, the things we remember.”

“Daniel Kahneman Wanted You to Realize How Wrong You Are.” Daniel Engber remembers a fascinating and important thinker: “Daniel Kahneman was the world’s greatest scholar of how people get things wrong. And he was a great observer of his own mistakes. He declared his wrongness many times, on matters large and small, in public and in private.”

“Desire, Dopamine, and the Internet.” L.M. Sacasas finds much to agree with in Ted Gioia’s recent essay bemoaning the rise of “dopamine culture,” but he explains why this framing might be inadequate: “the dopamine framing actually subsidizes the social imaginary that reduces the human being to the status of a machine, readily programmable by the manipulation of stimuli, which may itself be the deeper and more malignant problem.”

“Gulp Fiction, or Into The Missouri-verse.” In theory, Matt Seybold is reviewing Percival Everett’s new novel James, which is a kind of retelling of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim. In practice, Seybold crafts a wonderous, meditative essay on catching catfish, canonization, and American myths: “The hypercanonical novel is like a monster catfish, omnivorous and impervious, metabolizing everything in its path, predators and all, a roaring river demon growing ever stronger.”

“224 Feet of Fencing.” Brian Miller considers an essential skill for would-be farmers to gain: how to build a fence.

The Sacasas piece makes some good points, but it overlooks the fact that Big Tech often intends their products to be addictive and engineers them to that end. Many articles and quite a few books have been written about this, and I’m surprised that someone as perceptive as Sacasas seems to have missed it.

Comments are closed.