We are obsessed with the why of things. Why did my loved one die? Why do mass shootings continue? Why is there suffering in the world? Why evil? Yet why can sometimes be the wrong question. “I do not want God to ‘make it plain,’” wrote author and theologian Lewis Smedes on the death of his infant son. “I have given up asking why such bad things happen.” Smedes had a point.

How, the close cousin of why, interests me even less. I know how my mother passed: cancer. I know how my father and uncle died. Age and disease, alas, are the way of the world. There is little mystery to how my niece and my wife’s younger brother died. How my daughter, Jess, died is written on the death certificate: a fentanyl-laced heroin overdose. These details are crass, uninteresting, morbid.

But words like “eternal” and “afterlife” have taken on new meaning. Is my daughter happy and safe? I ask. Is she near, as close as a falling leaf or the taste of an apple or a distant hawk’s cry? Does she continue on? Tell me this that I may endure the rest: Where is she now?

Sometimes I quip to other bereaved parents that if angels appeared today—say Michael and Gabriel—my first response would be, “Mike, Gabe, glad to know you. Where’s Jess?” I have yet to meet a fellow mourner that did not nod in quiet recognition of my little joke. They, too, ask of their dead loved ones:

Where are they now?

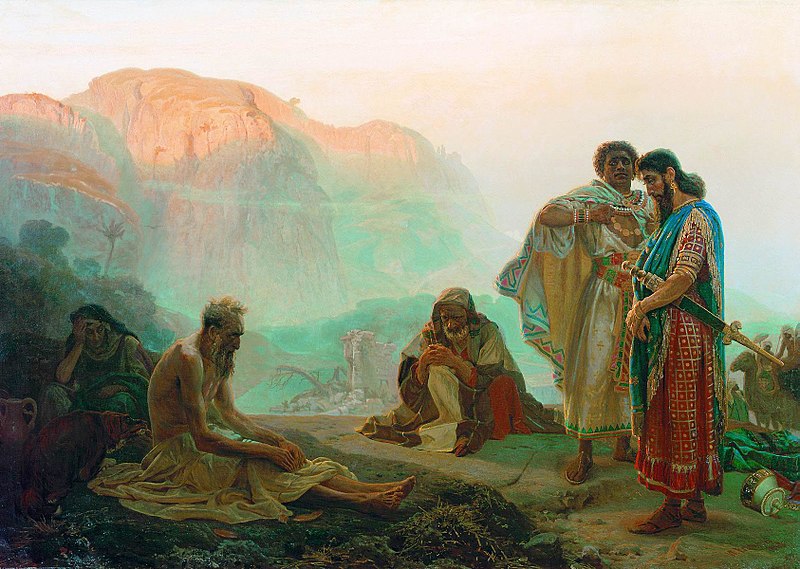

Mourners have posed these queries for centuries, in a tradition that traces its lineage to the Book of Job. In that story, the protagonist and his visitors tackle topics of suffering and the silence of God. They observe that we have a disconnect between what we perceive with our senses—the misery in this world—and what exists beyond them. Yes, we believe the soul exists, and yet, and yet.

God permits the slaughter of Job’s ten children, attacks on his health, and the loss of his belongings. Job quite reasonably insists that God’s hand is heavy. Then he surprises us. Job repeatedly identifies himself with “dust and ashes.” Katherine Southwood, an expert in the Hebrew Bible with the University of Oxford, explains that the words dust and ashes are frequently tied to mortality, human frailty, and mourning. “Job plans to try and console himself and grieve,” she writes, “[he] is just a mere mortal of ‘dust and ashes.’”

Job’s awareness of “dust and ashes” progresses from the outside in, according to Ariel Hirschfeld, professor of Hebrew literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Job is sitting in dust and ashes; then he is like dust and ashes; until at last he is dust and ashes. This final revelation “is the realm of the divine,” Hirschfeld concludes, when Job simultaneously inhabits the physical and invisible worlds, crossing the chasm between his skin and his soul.

Many mourners feel similar yearnings in the face of cold reality. We hope for a future reunion, at times we may even feel our loved ones near, bridging the gap between our physical and spiritual worlds. Then we blink, and like Job, are painfully reminded that here in the dust we must merely believe. “Have I enough strength to go on waiting?” Job despairs. We who have lost someone may ask the same question.

After a death, long-ignored rituals linger in our minds, often just below the surface. Without them—the funeral, music, and customs—we feel adrift. I saw this every day when I worked in a busy funeral home. People often turned to the Psalter for consolation, but not those hymns popular in Sunday services. Many believers seek psalms of lament in times of loss. These songs make up one third of the Psalter, and for good reason. They echo our sorrow from across the centuries.

For example, Job’s lament influenced the unknown author of Psalm 119, an important hymn used in Western mourning rituals. German tradition holds that 119 encompasses all other psalms. This is why Heinrich Schütz set it to music in 1671. When Schütz died a year later, his setting was performed at the funeral, along with a separate motet using Psalm 119 as composed by his former student, Christoph Bernhard. It was also the text for his memorial sermon: “I lie in the dust; revive me by your word. . . . I weep with sorrow; encourage me by your word.”

“I have spoken of the unspeakable and tried to grasp the infinite, but now my eyes have seen you,” Job declares when God appears at the end of the book. “Therefore I will be quiet, comforted that I am dust.” Rabbinical scholars and Christian theologians have wrestled with this enigmatic finale for millennia.

Semitic linguist Gustav Bickell saw relief in Job’s sudden awareness that there was in fact no explanation for his unutterable suffering. Author and translator Emile Joseph Dillon went one step further, suggesting that Job’s dust and ashes indicated complete surrender, “at once intelligible and wise.” Job sees at last that life’s pleasures and pains do not present themselves in easy formulae of punishment and reward. Rather, Dillon writes, “the explanation we seek, the light we so wistfully long for, will never come.” A leading authority on Job, Stephen Vicchio, emeritus professor from the University of Maryland, sees the protagonist’s consolation as one of finitude. This too speaks of relief. “His suffering may soon come to an end—and he is happy about that,” Vicchio writes, “for we are not God.”

Job’s surrender resonates with me. As a fellow bereaved parent, questions of why seem suddenly and absolutely trivial. I see Job’s comforting dust and ashes in purely practical terms. God appeared, eternity and the spiritual are real, and therefore Job’s children live on. The invisible world of the soul is as tangible as my skin and my heartbreak. There is hope of reunion. As answers go, it’s better than most. For Job, this may be the one comfort that matters. It certainly is for me.

The Book of Job has an unsettling mirror in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, yet the play holds a fond place in my heart. On October 30, 2009, I saw Hector Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. The next day I called my daughter for Halloween, one of her favorite holidays. I was in Manhattan to lecture at the American Translators Association’s 50th annual conference. That was my big news, I crowed, but Jess didn’t care. “You saw Faust on Devil’s Night?” she interrupted. “How cool is that?” My presentation is a distant memory, but Jess’s enthusiasm will forever bring a gentle smile to my lips.

Like Job, Goethe’s Faust also addresses concerns of dust and eternity, approaching them from a wholly different perspective. Both stories feature a bet with God over a man’s soul; each speaks to our struggle to embrace the spiritual when faced with a daunting physical world. But here the similarities take a shocking turn. Job was a bereaved parent, beset with poverty and horrifying malignancies. Misery consumed his world, as described by Emily Dickinson in 1862:

Pain has an Element of Blank It cannot recollect When it begun or if there were A time when it was not

Where Job’s abysmal condition had little to offer, in Goethe’s play, Mephistopheles overwhelms Faust with transient worldly joys. He provides shallow copies of all that was taken from Job. Faust has companionship, wealth, health, and the renewed vigor of youth. Fame, fortune, and excess are all his. These may prove temporary and insubstantial, but this seldom stops us from greedily consuming them as treasures of value. “Dust he will eat,” chortles Mephistopheles. “And he’ll like it.”

Faust falls prey to a common quirk—when things go well, the spiritual world may seem uninteresting if not unimportant. Soon enough he discovers that the world’s largesse is dust. Faust can tell little difference between the eternity of his soul and his gluttony of dirt.

Goethe created a vision of “an imperfect Job and an imperfect God,” observes Ilana Pardes, professor of comparative literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in which “the Lord’s ways are rather dubious.” Mephistopheles gloated to God, who accepted the wager, that he would have Faust wallowing in the muck “like my famed relation, the snake.” The tales have a similar goal: Faust and Job must betray transcendence and focus wholly on the tangible.

And yet, in the end, neither does.

As I write, my father-in-law lies nearly comatose in an Intensive Care Unit. Tonight questions of death and afterlife loom large in our lives. My thoughts naturally turn to my dad, dead these many years. He was a professional photographer. From him I learned that “forced perspective” is a filmic trick in which objects appear smaller than they actually are.

Grief, too, forces a new perspective. What we imagined was important recedes from view. Wealth and fame offer few lasting rewards; death and pain, surprisingly scant fear. Questions of why seem trivial. Suddenly we see with terrible clarity what matters most. We are desperate for any hint of our loved ones. Spare us homilies and theodicy, we may muse. We are surrounded by ashes and need to know: Where are they now? Will we see them again? After all, how they died is not nearly as important as who they were to us.

“Adonai has compassion,” sang the psalmist, “for he understands how we are made, he remembers that we are dust.” Perhaps in our dust of grief, we see clearly for the first time.

Image Credit: Illya Repin, “Job and His Friends” (1869) via Wikipedia