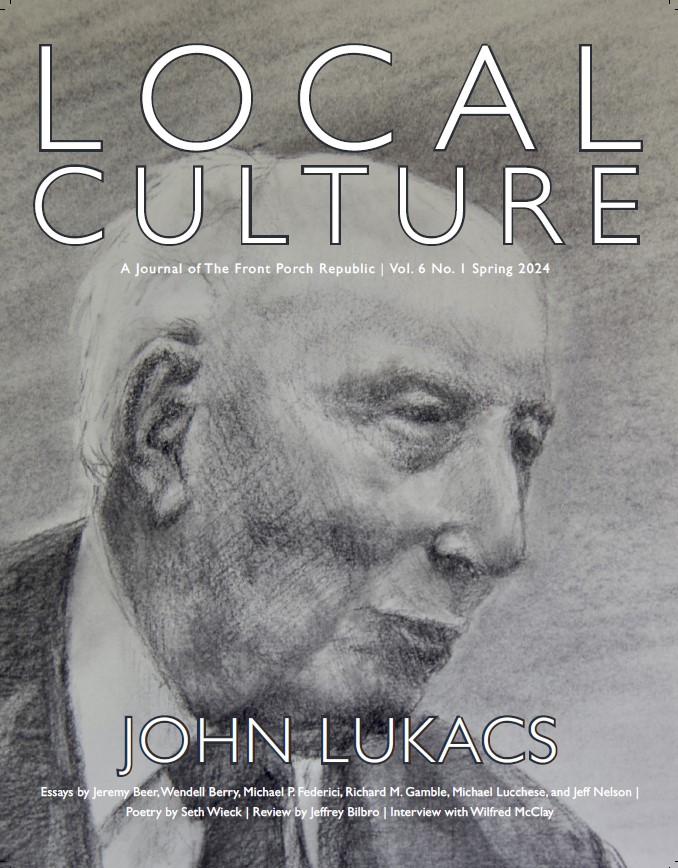

The spring issue of Local Culture is at the printers. Subscribe by Monday, April 29 to receive your copy in the mail.

In The Passing of the Modern Age (1970) John Lukacs said that “toward the end of an age more and more people lose their faith in their institutions: and finally they abandon their beliefs that these institutions might still be reformed from within.” He noted that at one time “when politics were rotten, people looked forward to a new kind of government; when government was tyrannical, people looked forward to a new political system.” But that was no longer the case: “disillusionment with politics and with government go hand in hand.”

Does this last remark still hold true? In an age of partisan rancor and mendacity much depends, I suppose, on who is in power and which news source you take intravenously before drifting off to sleep. Probably it does hold true, all things considered, though (case in point) as I write these words “All Things Considered,” NPR’s immodestly titled radio program, shows no signs of being disillusioned with its government.

In that remark Lukacs was doing one of the things he was so uncannily good at: looking from high above, surveying the broad sweep of historical patterns, and speaking in a concerned gravitas of what the long high view reveals about the doings and concerns and vicissitudes of men and nations and civilizations. Cardinal Newman, in The Idea of a University, spoke of the “great outlines” of knowledge and the necessity of apprehending them. Lukacs was someone concerned with these great outlines; he was also dexterous at tracing them, and it was this skill, not a mere news-cycle apocalypticism, that suggested to him that the age he was born into and in which he had a “happy unhappy life, which is preferable to an unhappy happy one,” was coming to an end.

It matters little, therefore, that Lukacs also noted in that same book that “a ‘conservative’ in Russia designates a Stalinist. In the United States ‘conservatives’ distinguish themselves by their espousal not of the Constitution but of the FBI.” Who, as spring awakens upon A.D. 2024 and the new baseball season commences, would credit such a remark—the latter half of it, at least? If only today’s self-designated liberals still had “Question Authority” affixed to the bumpers of their socially conscious cars. That old slogan—we are apparently fated to live under the tyranny of slogans—would be less a “threat to our democracy” than “I 🖤 the CIA and FISA.” No self-respecting person interested in conserving good things would drive around today boasting of such affections.

But this is only to admit that not all Lukacs said in that year, so proximal to Watergate and the forgettable Ford and Carter White Houses aborning, to say nothing of all those forgettable administrations following (for the managerial age has proven to be an age of managerial inadequacy)—this is only to admit that not all Lukacs said had the stamp of year-to-year durability. He was interested in what the end of an age looks like, and it looked to him then (as to many of us now) that the modern age was fading while a new dark age loomed. And backing him was Tocqueville’s distrust in the durability of man’s most ambitious enterprises; both doubted man’s ability to be as good as he himself and his enterprises need him to be.

Lukacs’s appeal comes in no small part from his distrust of centralization, bigness, and bureaucracies; it comes from his impatience with thought imperiled in the narrow straits of science and its applications, attended as usual with grinning assurances from both Scylla and Charybdis that we’re sailing safely in calm blue waters under the open sunshine of progress. He was at pains to expose the limitations of the specialist, limitations that perforce derive from inveterate and ineradicable human limitations, to say nothing of those imposed by nature. But he also evinced a devotion to place and to settlement, to the world of books and humane learning, which education once concerned itself with before it became mere training in the advanced arts of getting and spending.

John (Janos Adalbert) Lukacs, who in Confessions of an Original Sinner admitted “a weakness for coincidences … especially for chronological ones,” was born in Budapest on January 31, 1924, “seven days after Lenin died and two days before Wilson died.” His father was a doctor and a Roman Catholic; his mother was Jewish. They divorced when the bookish Janos was eight. He regarded himself a Socialist until, in 1938, his mother sent him to study in England and he met an English Socialist, “a decent man, an English idealist, full of illusions that had but a frail relationship to reality.” This “Mr. Harrington,” one of Lukacs’s teachers,

disbelieved (or at least professed to disbelieve) in the existence of national characteristics. Disarmament, Collective Security, National Self-Determination, the injustices of the Versailles Treaty—in 1938 he still professed to believe in them. He wouldn't believe that the German masses were solidly behind Hitler; nor did he realize that Hitler was the main beneficiary of Wilson's disastrous proposition of national self-determination, in virtue of which tens of thousands of Austrians and Sudeten Germans pelted him with flowers as he drove slowly through their streets.

Thus did Mr. Harrington set his young pupil on another course.

Lukacs returned to Hungary and earned a degree from the University of Budapest. In July of 1946 he fled to the United States, shortly after the Soviet’s Siege of Budapest had put an end to the Nazi occupation of Hungary. He taught briefly at Columbia University before being hired in 1947 to teach full-time at Chestnut Hill College in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, where he remained even after his retirement in 1994. Lukacs died May 6, 2019.

The New York Times was charitable to him in its obituary: he was “a maverick historian, prolific author and self-professed reactionary whose views on politics, populism and pop culture departed from those of doctrinaire liberals and conservatives alike.” The paper of record also took a break, if only briefly, from its wonted tone-deafness:

Mr. Lukacs envisioned a dystopia very different from the one Orwell foresaw but equally oppressive. His version of the future, he wrote in The New York Times Magazine, was already visible in two Pennsylvania structures not far from Philadelphia: the King of Prussia shopping mall and General Electric’s Valley Forge space complex.

He saw these vast, impersonal edifices as the products of “planners, experts and faraway powerful agencies” who disregarded the will of the people — “our voices, our votes, our appeals.”

“It is a sickening inward feeling,” he wrote, “that the essence of self-government is becoming more and more meaningless at the very time when the outward and legal forms of democracy are still kept up.”

What follows is intended to be a kind of Lukacs Sampler, an appetizer to whet the appetite.

He minced no words on the state of craftsmanship and the artistic movement we call “modernism”: The artisan is no longer a craftsman but “a person,” he sneered, “of unusual, indeed, superior sensitivity,” and modern art itself is “a drastic and brutal departure from the traditions and the achievements of the Modern Age.” It is “marked by an increasing tendency in letters, buildings, music, painting, poetry, to ugliness.”

The sexual revolution fared no better in his general critique of the modern age:

The problem of sexual, that is, of carnal morality is at the center of the moral crisis of our times; it is not merely a marginal development. The overwhelming majority of its commentators say (though they do not always think) the contrary. They believe that the newly found freedom in sex is only a long overdue consequence of the broader realization that the old forms of tradition and society no longer serve. They could not be more wrong.

Allowing for the abundance of companionable pet dogs marriageable young women are settling for, to say nothing of the paucity of marriageable young men, can we find firmer grounds for dismissal in today’s academy than this remark: “many women have gained their ‘independence’ at the cost of increasing loneliness”? Lukacs was fearless—he seldom seemed in the least bit fearful—in commenting on what emancipation for women really meant:

After about 1800 the bourgeois morality of the nineteenth century was breaking up. The prime result of this in the first decades of the twentieth century was what people, rather euphemistically, would call the emancipation of women. Legally, politically, socially, women were now to enjoy all of those privileges that had been, by and large, the monopoly of men. Some of these reforms were overdue and reasonable. Most of their results were extremely confusing since they involved ultimately not so much the legal or the social as the sexual situation of women.

The sexual revolution, Lukacs said, moving full-steam ahead, had not expanded women’s dignity so much as reified their status as mere sexual objects. “They were back where they started from…. For the liberal prophecies were, as usual, wrong. Their baneful consequences abide with us. The emancipation of women has not led to a more harmonious understanding between the sexes. Prostitution has not disappeared; venereal diseases went on fluctuating; illegitimacy rose rather than fell.”

This freedom came after a long and liberating march toward more democratic forms of government. But are they democratic? “In the long run the rule of aristocracy has been succeeded not by the rule of democracy but by the rule of bureaucracy,” he said, noting that “by 1956 the majority of the American population were no longer engaged in any kind of material production, either agricultural or industrial. They were employed in administration and in services.” Bureaucracy had won the day “not only in ‘government’; also in every kind of so-called ‘private’ institution.” And as for the “democratic exercise of periodic elections”: it has failed to “compensate people sufficiently against their deep-seated knowledge that they are being ruled by hundreds of thousands of bureaucrats, in every level of government, in every institution, on every level of life.”

You might be tempted to call this, perhaps with a hat tip to Philip Rieff, the Triumph of the Bureaucrutic. Like the automated answering system at the far end of your utility company’s 1-800 number, The Bureaucracy, an otherwise nameless and unidentifiable power whose purpose is to make you go away while it continues to take your money, becomes a brutish leveler of old grievances, a remote-controlled bulldozer in the briar patches of public and political discourse. For in this state of affairs the Left-Right divide loses its meaning no matter how fiercely the frothing denizens on both sides of the trench continue to cling, at this late date, to their meaningless distinctions. Lukacs, for his part, believed that our ever-widening political divide is not so much between Left and Right anymore as between those who have and those who have not lost their faith in the gods of Progress. Like Tocqueville he noted the tendency of movements to betray themselves by taking on the garb and guidebooks of their enemies:

"Liberals", who, earlier in the Modern Age, had advocated limiting the power of the state, have throughout the twentieth century advocated government intervention in many fields, including a guarantee to welfare of many kinds. "Conservatives", who had once stood for the defense of traditions, have become chief advocates of technology and of militarization and even of populism, all in the name of Progess.

For reasons that this passage pretty clearly suggests, Lukacs called himself a “reactionary.” This was in Confessions of an Original Sinner (1990). The publication date is telling, for by then—three-fourths of the way into the Reagan-Bush succession, soon to be followed by eight years of Clinton—“liberal” and “conservative” were terms no longer available to him. Between the two of these “conservative” is the more likely moniker, but in that case “conservative” cannot be used in its nonsensical—which is to say its debased political and journalistic—sense. (Whether it can be used, or whether anyone desires it to be used, in the “Burke-to-Kirk” sense is another matter.) Lukacs had little patience with the self-styled “conservatives” of his moment—namely, those in that lineage extending from Joseph McCarthy to Dick Cheney: “Conservatives,” he said, “especially in the United States, are some of the most strident proponents of ‘Progress’; their views of the present and the future are not merely shortsighted but laden with a bellowing optimism that is imbecile rather than naïve.”

In what does such “bellowing optimism” consist? These “conservatives” have shown no interest at all in conservation or permanence, and therein lay a signal cause of what we imprecisely and lazily call “environmental” degradation. Lukacs deplored our habits of settlement, which aren’t habits of settlement at all but a frenzy of mobility and impermanence: He himself had moved from Budapest to Pennsylvania, but after this move in 1946, born of political necessity, he stayed put, and it was from home that he disapproved of the “constant movement of the population”; he said that what threatens nature and our quality of life is not so much “the want of scientific foresight,” though that is indeed a problem, as our “want of permanence”; “man’s destruction of nature is involved with his destruction of himself, and not necessarily in a sequential order.” Not the usual suspects at the end of the pointed finger—such as “other people”—but “the degeneration of [man’s] self-knowledge may be the cause, and not the consequence, of his destruction of nature.”

Lukacs was also a careful student of the history of science and especially of the implications of the New Physics, which had called certainty itself into question. But he insisted on the “priority of historical over ‘scientific’ thinking.” He seemed to concur with the French physicist Pierre Duhem that “the history of science alone can keep the physicist from descending into grave error.” Lukacs allowed that Cartesian and Newtonian science has “led to the fabulous capacity of mankind to manage things,” but he also warned, rightly, that science amounts to “a probabilistic kind of knowledge that has its own limits, due to the limitations of human nature.” And so “the kind of science that is incapable of thinking in other categories than in those of mechanical (and therefore predictable and calculable) causes and effects, that has eliminated the notion of purpose from the world, has not much more to tell us; indeed, it is the principle agent of the destruction of nature and of man.”

Like many readers of LC Lukacs took a dim view of centralization, but he was not sanguine about efforts to decentralize, mainly because “people have become distrustful of the kind of men and women who are interested in holding this kind of power at all.” In other words, even the decentralists, insofar as they seek power of any sort, may, at the end of an age, prove to be untrustworthy.

Nor could we accuse Lukacs of auditioning for a job in any of the thousands of DEI offices nationwide:

Justice is of a lower order than is truth, and untruth is lower than is injustice. The administration of justice, even with the best intentions of correcting injustice, may often have to ignore or overlook untruths during the judicial process. We live and are capable of living with many injustices, with many shortcomings of justice; but what is a deeper and moral shortcoming is a self-willed choice to live with untruths.

This self-willed choice for untruth calls to mind Voegelin’s quip about preferring certain untruths to uncertain truths. According to Lukacs it is a feature of an age about to end. And there are others. “At the end of the Modern Age constitutions and courts have extended lawfulness to private acts of all kinds (sometimes to the extent of obscenity)—at a time when fewer and fewer people appreciate or are able to cultivate privacy.” (Again, this accords with Tocqueville, who, mindful of human fallibility, observed that original intentions turn into their opposites when torn from their necessary cultural and religious contexts.)

Another feature of an age about to end: The sign of wealth is debt. Note the number of people who actually only rent the houses they “own.”

And another: As classes disappear people feel uncomfortable and “are unable to identify themselves” and therefore “depend on paltry and temporary associations.”

Yet another: The technologies of communications get more sophisticated as real communication disappears.

And let us be aware that dangers may arise “from fake spiritualisms of many kinds—from a spiritual thirst or hunger that arises at the end of an age, and that materialism cannot satisfy.”

Is it any wonder that we pour large amounts of money into education even as more and more people know close to nothing about the world? Since the revolts of the 1960s students (and in due course their professors) have been dissatisfied and angry about the content of education, even as they “come face to face with the dissolution of learning.” And yet few seem to notice that one of the greatest threats to education is specialization, to say nothing of the “specialization of specialization,” which is less an enlargement than a fragmentation of learning; it comes “at the expense of understanding, unity, synthesis.” (Recall Max Weber’s “specialists without spirit, sensualists without hearts; this nullity imagines it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.”)

So in this rapid-fire survey I come around again to what Lukacs was so good at: understanding, unity, synthesis. In an age ravaged by the effects of shortsightedness and fragmented “knowledge”—the “knowledge” of the specialist—this capaciousness of mind, this power of synthesis, is perhaps the unum necessarium. It is certainly one of Lukacs’ greatest contributions. And he knew whereof he spoke when he said that men and women in his vocation, which was to teach, must point out “all kinds of public untruths, very much including those propagated by the established public intellectuals.”

Lukacs did not write as a tabulator of mere facts and certainly not as a haruspex divining entrails. (He did not think historians should be in the soothsaying or anthropomancy business.) He wrote, rather, as an observer of a world infused and imbued by thought—that is, of history, which is an account not of material causation but of man thinking. Historians, according to Lukacs, traffic not so much in facts as in events, for they (and we) do not so much record as remember the past. Thus Lukacs, turning a skeptical glance on the Marxist project, could credit neither the “‘schools’ of social history [that] depend on the concept of Economic Man” nor the “‘scientific’ belief that the basic realities of human existence and of historic life and development” form the material on which we build the “superstructures” of “mores and morals and thoughts and beliefs.” Marx may have stood the world on its head; Lukacs, for his part, returned the favor, restoring both man and the primacy of thought to their rightful places:

My belief, from an early time in my life, has been ... that (perhaps especially in the democratic age and in democratic societies) the most important matter is what people think and believe—and that the entire material organization of society, ranging from superficial fashions to their material acquisitions and to their institutions—are the consequences thereof.

There is something Augustinian in Lukacs’ view of the past—that in a real sense, or at least in a manner of speaking, it exists only in the present, for it is only in the present that by remembering we call the past from nothingness into being. But for Lukacs this was more a matter of insisting that human thought comport with a viable view of the relation of mind to matter, a view won by quantum physics, alongside and yet independent of philosophy, that had called into question (perhaps unwittingly) the basic assumptions of the entire scientific project. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle did not preserve inviolate our vaunted objectivity nor our Cartesian commitment to the existence of matter independent of mind. We learned, or should have learned, that it was no longer possible to think of anything as enjoying a holiday from thought. Lukacs called this “participant knowledge.” It is noteworthy that a principal tutor in this for Lukacs was Owen Barfield, whom Lukacs regarded as one of the 20th century’s most important thinkers.

This is not the place for a full-throated rehearsal of what was essentially a romantic revolt against a towering but oafish empiricism. (Giants, Barfield had observed, are strong but also stupid.) Let it suffice to say that Lukacs joined the revolt. He would have much to say about the relation of history to science—contrary to popular belief history, not science, is in charge—and much more to say about many of our most vexing problems, including the threats posed by experts, specialists, bureaucracies, centralization, hyper-mobility, and the mad myopic maniacs who, in contempt of all human limits and the severe lessons visited upon us by our many failures, insist upon the complete conquest and control nature.

Image via Flickr

From 2001 until 2008 every other car in lib LA had a “Question Authority” bumper sticker. They all disappeared in January 2009. Dissent was no longer patriotic. I supposed they all reappeared in January 2017, I was gone by then, although nonsense about “Resistance” was more in fashion then.

This sums up the second half of the 20th century perfectly:

“Bureaucracy had won the day “not only in ‘government’; also in every kind of so-called ‘private’ institution.” And as for the “democratic exercise of periodic elections”: it has failed to “compensate people sufficiently against their deep-seated knowledge that they are being ruled by hundreds of thousands of bureaucrats, in every level of government, in every institution, on every level of life.””

The “New Class” won, all over the planet. One wonders if Ike could have done anything about it, since he obviously recognized the dangers and the way things would go, or if by the time he came to office it was too late to do anything but go along.

“the mad myopic maniacs who, in contempt of all human limits and the severe lessons visited upon us by our many failures, insist upon the complete conquest and control nature.”

That’s a fool’s errand, of course, and their time is almost over, but there’s great pain for all of ahead because of them and their delusions.

Thank you for your sublime discourse on the thought of Professor John A. Lukacs, who was my major professor at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia. You captured his essence and his thinking in your succinct and thoughtful article.

A quote from the text: “He wrote, rather, as an observer of a world infused and imbued by thought—that is, of history, which is an account not of material causation but of man thinking.”

I point out to my students that event which occur along the space/time continuum are not history. History comes into being when these events are contemplated and articulated. Of course, those articulations are themselves events along the space/time continuum.

A quote from the text: There is something Augustinian in Lukacs’ view of the past—that in a real sense, or at least in a manner of speaking, it exists only in the present, for it is only in the present that by remembering we call the past from nothingness into being.”

I ask my students how one divides happenings chronologically. They usually answer: past, present, future. I then give them a sentence, telling them to listen closely, such as the following: “I am telling you something.” I then point out to them that as I utter the “something,” the rest of the sentencd is already in the past and the future is yet to be, the future often used by ideologs as a false enternity. It is actually the present which is the portal, window or icon into enternity and not the future. The present is a rapidly moving line, not unlike the rapidly moving line the sun casts at 12 noon across the globe, for somewhere on the globe, everyday, 12 noon is moving around the sphere at 1000 miles per hour.

Comments are closed.