The Industrial Revolution had been churning for a hundred years. Results were impressive. Standards of living were climbing. Sure, urban slums were miserable, but many historians believe they beat the squalor in rural villages.

But industrialization was messy and not just from a pollution standpoint. Labor itself was messy. There was no good way to measure labor efficiency, so workers “soldiered” (expended the minimum effort required to avoid getting fired). Because labor was plentiful and cheap, factory owners didn’t much worry about it. They accepted that’s “just how things are” and threw a lot of labor hours at projects that probably could’ve taken a lot less time.

Then Frederick Winslow Taylor brought a stopwatch to work at the Midvale Steel plant in 1881. He started timing the workers’ every movement, breaking down each job into smaller steps and timing them, then re-assembling the movements in different ways to see which combinations were fastest.

Productivity at the Philadelphia plant soared. Scientific management was born. Twenty years later, at age 45, after he had made millions through consulting fees and patents, he retired and focused on spreading the good news about scientific management.

He assured readers and listeners that scientific management would, in the words of Nicholas Carr, bring “a utopia of perfect efficiency.” It would bring “maximum speed, maximum efficiency, and maximum output.”

Whereas the Industrial Revolution previously bellowed, now it would hum. The same principles of scientific management would be applied to business in the Electronic Age. Today, they govern business in the Digital Age.

Neil Postman was one of America’s best twentieth-century media theorists and social critics. In his 1993 book Technopoly, he distilled the six assumptions that drove Taylor’s system of scientific management.

- The primary, if not the only, goal of human labor and thought is efficiency;

- Technical calculation is in all respects superior to human judgment;

- Human judgment cannot be trusted, because it is plagued by ambiguity and unnecessary complexity;

- Subjectivity is an obstacle to clear thinking;

- What cannot be measured either does not exist or is of no value;

- The affairs of citizens are best guided and conducted by experts.

Taylorism was merely the philosophical Enlightenment of the eighteenth century applied to the Industrial (then Electronic then Digital) Revolution. Isaiah Berlin said the Enlightenment’s ideals could be summarized in three points:

- Every genuine question can be answered. If it can’t be answered, it’s not a genuine question;

- The answers to the questions can be discovered, learned, and taught;

- All the answers are compatible with one another.

It’s no coincidence that the Industrial Revolution was merely an extension of the Enlightenment. Both exemplify what happens when the left hemisphere usurps the right hemisphere’s proper role as the master.

Iain McGilchrist published his bestseller, The Master and His Emissary, in 2009. He followed it with his massive two-volume The Matter with Things, in 2021. They’re daunting and nuanced works, but they can be boiled down to three points:

- The left hemispheres and right hemispheres of our brains do the same things.

- But they approach things differently: they attend to the world differently. Among other things, the left hemisphere attends to the world for purposes of acquisition. It is “tasked with tasks.” Projects, efficiency, and utility are proper to its role. It allows the body to survive. It’s practical.

- Even though the right hemisphere is supposed to be the master, the left hemisphere has usurped the master role. Modern culture is a left-hemispheric culture, and it’s creating all sorts of problems.

The Enlightenment was the intellectual classes’ mental world getting distorted by the left hemisphere’s way of looking at things. The Industrial Revolution pulled the rest of society into the distortion. This is how McGilchrist put it in a recent interview on CBC radio:

One of the most daring maneuvers of the left hemisphere is the Industrial Revolution. We began a full-scale onslaught of the natural world, [thinking] that we were the masters and that we could control and exploit mere material, as we saw the natural world, something there for us to utilize. We saw machines, we saw a landscape, that was increasingly molded by our efforts to slice through it with railway lines, to carve tunnels, to put our stamp on nature.

Industrialization reshaped our landscapes and urban areas with left-hemispheric precision. The countryside was scarred by the left hemisphere’s efforts (a process decried by G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc and later lamented by Wendell Berry). The urban areas became ruled by left-hemispheric efforts. As a result, everyone increasingly started to see things with their left hemispheres.

There have been areas of resistance, like Chesterton and Berry, like Coleridge and the Romantics, like the Beatniks. Front Porch Republic is, in my opinion, the leading resistance movement on the web. The problem is, these are all more like a guerilla resistance than a full-scale pushback by the oppressed right hemisphere. I applaud the resistance movements, and they’ve offered a needed reprieve from the left hemisphere’s relentless drive, but they haven’t been terribly effective.

Despite its ineffectiveness, such guerilla resistance has grown tiresome to the left hemisphere, which strives to eliminate right-hemispheric resistance altogether.

The digital world is dominated by the left hemisphere.

Frederick Winslow Taylor’s stopwatch and belief in management by experts was a perversion of efficiency. But compared to Google and artificial intelligence? Such things were primitive.

Google, for instance, is a company ruthlessly driven by left-hemispheric principles.

Google doesn’t believe that the affairs of citizens are best guided by experts. It believes that those affairs are best guided by software algorithms—which is exactly what Taylor would have believed had powerful digital computers been around in his day. Google also resembles Taylor in the sense of righteousness it brings to its work. It has a deep, even messianic faith in its cause. Google, says its CEO, is more than a mere business; it is a “moral force.” The company’s much-publicized “mission” is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. . . . In Google’s view, information is a kind of commodity, a utilitarian resource that can, and should, be mined and processed with industrial efficiency.

When people looked at the material world after the left hemisphere scarred and molded it, they increasingly looked at things with their left hemisphere. When people look at the screen, they are looking through left-hemisphere windows.

This is a serious problem.

McGilchrist wrote The Master and His Emissary to address the dominance of this perspective. The left hemisphere has taken over our minds and reshaped the world in its image. It’s getting stronger and stronger at the expense of the right hemisphere. It’s bad for humans, bad for the culture, and bad for the planet. As McGilchrist explains,

A way of thinking which is reductive, mechanistic has taken us over. . . We behave like people who have right hemisphere damage. . . . [The left hemisphere] treats the world as a simple resource to be exploited. It’s made us enormously powerful. It’s enabled us to become wealthy, but it’s also meant that we’ve lost the means to understand the world, to make sense of it, to feel satisfaction and fulfilment through our place in the world.

All of us need to revive our right hemispheres. We owe it to ourselves; we owe it to society.

It won’t be easy. The left hemisphere has built a material world and online world that is molded to its rigid way of thinking, and it is highly intolerant of anything that isn’t. Anything that stands in the way of the speedy collection, dissection, and transmission of data is a threat not only to Google’s business but to the new utopia of cognitive efficiency toward which the digital world aims. Reviving our right hemispheres is the difficult but vital work we must undertake.

Many historians and philosophers consider Descartes the father of modernity. “I think, therefore I am” put our rational faculties on the highest level, thereby setting the stage for the Age of Reason, the Enlightenment, and much of modern thought. It’s no coincidence that McGilchrist takes serious aim at Descartes, speculating that the seventeenth-century Frenchman may have been deranged.

It’s also no coincidence that the best thing we can do to engage our renegade left hemispheres and make a stand against its usurpation is to get outside the modern rationalistic mindset that Descartes set in motion, to adopt a disposition—a way of seeing things—that doesn’t depend on what Russell Kirk referred to as “defecated rationality.”

We need to embrace forms of knowing that do not rely exclusively on rationality. We need to embrace what Michael Polanyi called tacit or “personal knowledge.” Or what James O. Taylor called “poetic knowledge.” We need to respect the implicit, the subtle, and the paradoxical.

Closely related to this is cultivating a deep distrust of decontextualized objective facts and a distrust of those legions of left-hemispheric minions (“experts”) who wield their “objective facts” like weapons.

In our daily lives, we need activities that aren’t driven by our left hemispheres. We need leisure (as understood by Josef Pieper). We need to waste time. We need to do nothing . . . a thing that rankles the left hemisphere’s productive disposition.

We should also do things that are pointless. Reading poetry is one of McGilchrist’s favorites (the right hemisphere appreciates poetry’s implicit meaning; the left hemisphere prefers prose’s explicitness). We should read for recreation. We should play but without competition (a left-hemispheric trait). We should cultivate the ability to listen, which, of all the senses, is passive and receptive—attitudes disdained by the left hemisphere.

It’s a cliché, but I think McGilchrist would embrace the saying, “We’re human beings, not human doings.” We occasionally need to embrace the simple act of existence. Cultivating this way of being will strengthen our right hemispheres and help restore in us the balance a healthy life requires. And when we practice these forms of resistance with others, we help restore in our culture the balance that a healthy society requires.

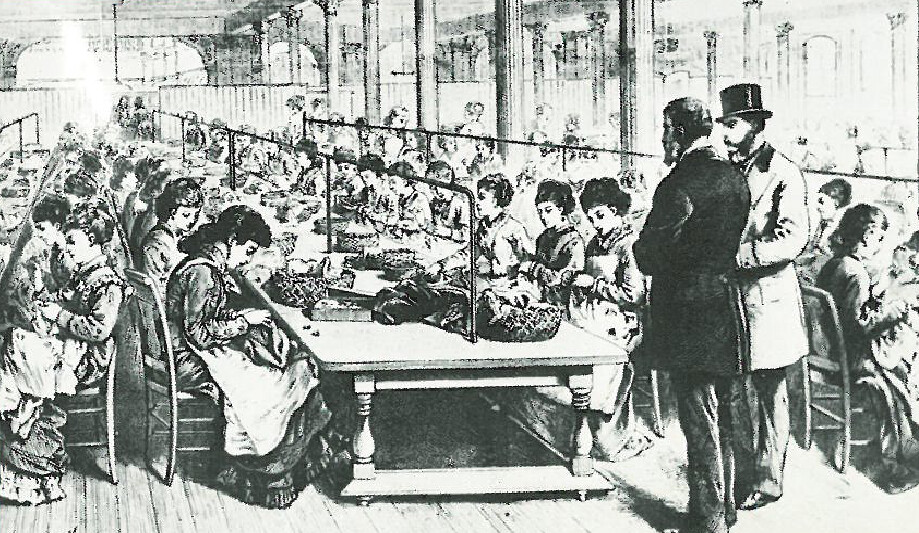

Image via Flickr

All that talk about the Industrial Revolution but it was really World War II when The Machine completely took over and never let go. Eisenhower warned about the perils of Big Government, Big Business, Big Academia, Big Everything as he walked out the door, but did nothing about it while he was in office. Probably he couldn’t, though he saw the danger.

“Front Porch Republic is, in my opinion, the leading resistance movement on the web.”

Good grief, the average article here gets zero comments, let’s not lose our grip on reality.

Likewise, Brian, I do wonder why FPR generates so few comments.

I am also nostalgic for the threads of comments that made it to the hundreds back in the early days of FPR. It was formative for me at the time. The trolls from those days look so quaint now.

I’d say the easy answer for the decline of comments at FPR and most other sites is Twitter and other social media platforms–you can get credit on your own platform for those comments, where I’d classify good comments on the site of publication as something more like a public service.

I’ve got McGilchrist lined up to read this summer and I’m looking forward to it. Thanks for the preview, Eric.

Mr. Scheske,

Thank you for the super helpful and inspiring article!

This was great to read and I love FP for these articles. Thank you!

Thank you, everyone.

With respect to “leading.” Perhaps I should’ve used a different adjective, but I didn’t mean “biggest” or “most influential.” I meant that FPR is, by disposition, the leading resistance movement. I find its attitude, its approach, its worldview . . . whatever . . . to stand athwart everything our modern left-hemispheric culture pushes on us.

One slice of support for my belief: McGilchrist doesn’t make a lot of references to Wendell Berry, but he’s a fan. ‘Life is a Miracle” is included in “Iain’s Top 30 Books for ‘The Matter with Things.'” Given that The Matter with Things’ bibliography runs over 180 pages and contains over 4,000 entries, it’s a high honor. I’ve provided the link to the list below, but I’m afraid you must be a paid McGilchrist Channel subscriber to see the list.

https://members.channelmcgilchrist.com/iains-top-30-books/

Comments are closed.