My grandfather and I walked the pasture above the Linkous-Kipps house. It was built by Henry Linkous in 1799 and owned, at that time, by my great-uncle Linkous, an auctioneer whose baritone voice rolled like distant summer thunder. But it was not summer now. It was still winter, and we were hunting rabbits, but we saw no rabbits, only the dim winter grass, brown and tough with cold.

We tromped about the field with shotguns cradled in our arms. My grandfather held a single-shot 12-gauge, smooth with age and without even an indicator at the end of the barrel. The butt was short and made of an unknown wood. A simple latch released the break. Its long barrel pointed like some hollow and gaunt finger at the object of its blast. As a young man, he had bought the gun from a neighbor. Its existence before this acquisition was a mystery, one “as old as the hills.” My grandfather held the butt between his side and arm. The rest of the shotgun draped over his arm like a dishtowel, ready to be snapped into action.

The afternoon was cold, an unaccountable day between spring and winter. But we didn’t mind. We knew that a hot supper waited for us on Brush Mountain. And given the dignity of our afternoon intentions, we would eat with a renewed appetite, regardless of our success. We walked along the fence line and tried to flush a small thicket. Nothing.

We continued along the ridge and stopped at the top of a knoll. Out across the valley, the developers had begun scraping the countryside. Bulldozers cut outlines of progress in crude brown strokes of upturned ground. Such developments were cropping up across the New River Valley, crawling like the inevitable movement of dandelions across a field. I understood that such houses could become warm homes. But the twinge was unavoidable.

Not long ago, the bucolic valley was a quiet rural town with quiet ambitions. As a youth, my grandfather delivered the mail to the Huckleberry, a train that originally carried coal from Merrimac Mine to the Cambria Depot. Later, it carried students to the then small land-grant university, Virginia Polytechnic Institute (Virginia Tech). Even into the 1980s, well after the Huckleberry lost its preeminence, the Christiansburg shopping mall was still an orchard. The Olive Garden was an actual garden, and the buzz of traffic was the buzz of pollination.

Such new construction produces in my mind a knee-jerk, “stop!” But the world will not stop. And the problem is not really the new construction. While I’ll be the first to level aesthetic and ethical critiques at the sprawling cookie-cutter suburbs, the real ache lies elsewhere. It lies in the very nature of growth. Even healthy growth involves loss, and this loss reminds us of our exile, our search for an abiding home. We don’t need to villainize the present or idealize the past to feel the ache.

“No rabbit stew, today,” my grandfather said. We began our retreat but decided to signal our armistice to the rabbits with a little target practice. It’s difficult for a young boy to go hunting and not fire his shotgun. My grandfather recognized that particular anxiety. We found a good spot.

After I emptied some .410 shells on a few unsuspecting logs, my grandfather took his position. He raised the long barrel and took aim at a nearby stump. The family patriarch stood with arms extended. I imagine that Moses held his staff in a similar way when he stretched it over the Red Sea. When Pops fired, the shotgun jolted in his hands like a living creature. Animated by the brief explosion, it threw his shoulders back and nearly knocked him down. A brief pause. He regained his footing, looked at me, and laughed. I laughed too. As we walked back to the truck, he slowly rubbed his shoulder, smiling.

A decade later, I carried the old shotgun to Kentucky. My grandfather gave it to me inside an ancient leather case that could have emerged from the pages of a Louis L’Amour novel. He received it, along with a wind-up record player, from his great uncle, a Word War I veteran and secretary to the Pearisburg, VA congressman. It was a proper housing for the Appalachian totem.

There are still no rabbits. To shoot the ones in our neighborhood would lack any passing resemblance to sportsmanship. It would be like shooting a lazy basset hound or a fat campus squirrel. And so the shotgun sits in our home like a quiet benediction. It dreams—as I do—of long walks in the valleys of my youth and whispers of future pastures that are untrod and unspoiled.

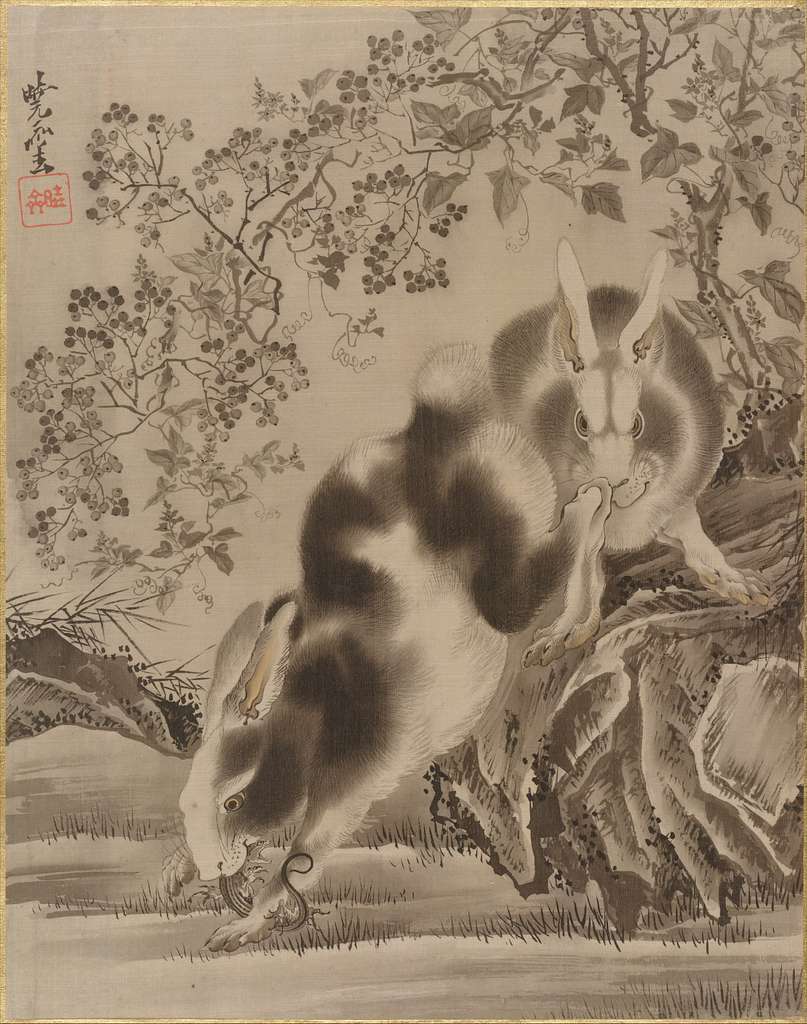

Image Credit: Kawanabe Kyōsai, “Rabbits” (1887) via Collections – GetArchive

An evocative vignette with your signature beautiful prose. Thank you for sharing.

This was beautifully written. Thanks.

Comments are closed.