“The Cultural Roots of Our Demographic Ennui.” Patrick Brown argues that affluence—what regular FPR contributor John de Graaf labeled “affluenza”—lies behind many of our cultural ills: “A world of creature comforts is not one that demands sacrifice. And with greater wealth comes less need for solidarity and interdependence. Who needs to invite neighbors over for a barn raising when you can just hire a general contractor? Of what use is the church’s traditional function of mutual aid in the era of commercial life insurance? A passport full of ‘experiences’—cliff diving in Bali, experimenting in Amsterdam—can help one ‘find oneself’ without the messy interpersonal dynamics of belonging to a church or social club full of people who know your flaws. ‘Neighbors’ are the people who happen to have bought houses near you; similar in net worth, perhaps, but without the presumption of any shared background or values.”

“Why the Pandemic Probably Started in a Lab, in 5 Key Points.” Alina Chan breaks down what we know and what we don’t know about COVID’s origins in this essay for the New York Times: “People of all nations need to see their leaders — and especially, their scientists — heading the charge to find out what caused this world-shaking event. Restoring public trust in science and government leadership requires it.”

“The Artificial Pancreas.” Peter Mommsen kicks off the new issue of Plough with a thoughtful exploration of how we might thrive amid the shifting technological ecosystem: “Both Postman and Haidt, in different ways, help us to see that the challenge of tech is collective. Our response, too, must be collective; lonely acts of defiance, while often necessary, only get you so far. If, as seems likely, we’re facing another round of Postman’s ‘ecological’ change, we must become all the more active in nurturing flesh-and-blood communities that are robust enough to keep technology in its place. That can be as simple as a network of parents setting common norms for their families. Or it can be a circle of friends, a school, a company, a church, or a commonwealth. Whatever the form, a strong communal culture can push back against pressure from technologies to shape humans in antihuman ways.” Among other good essays in this issue, don’t miss Brian Miller’s ode to the humble rock bar.

“Private Equity–Backed Firm Bowlero Is Ruining Bowling.” Amos Barshad chronicles how one corporation is buying up bowling alleys and turning them into entertainment palaces where the bowling itself is second-rate: “It all feels thoroughly American: in the interest of short-term profit, a corporation goes about methodically worsening a beloved national pastime. Do you sometimes ask yourself, why does it feel like everything is getting worse? Bowlero provides one possible answer: because somewhere, someone’s making money off the decline.” (Recommended by David Mills.)

“The Ghost in the AI Machine.” Gene Callahan warns that some AI enthusiasts act more like alchemists than sober-minded realists: “Intelligence can be defined as the use of reason to achieve some aim. . . . Even in the least practically oriented use of intelligence, there is still some aim: to understand the nature of the prime numbers, or to contemplate why the universe exists. But ChatGPT and its ilk have no aims.”

“How 3M Executives Convinced a Scientist the Forever Chemicals She Found in Human Blood Were Safe.” Sharon Lerner’s extensive reporting on PFAS chemicals, their ubiquity, their harms, and their profits, is stomach-churning: “Much of my reporting, which started in 2015, focused on what 3M and DuPont knew, even as they continued to produce PFAS. But, as I reported on the cover-up, I wondered what it meant for a sprawling multinational company to know that its products were dangerous. Who knew? How much, exactly, did they know? And how had the company kept its secret?”

“A Past in All Its Fullness.” Nawal Arjini interviews Peter Brown about travel, languages, and historians: “Each age produces its own historians with their own ways of asserting the truth. Perhaps the most urgent need we have today is to develop a sense of the strangeness of the past and a sense of urgent searching for the truth to ensure that the past is not forgotten, or flattened by being presented as so “like us”—no more than a mirror of ourselves—that it can be manipulated without challenge.”

“What do Agroecological Farmers Think about Agritech?” Ayms Mason, Pat Thomas and Lawrence Woodward put together a report on how agroecological farmers in the UK approach new digital technologies. They didn’t find any iron-clad rules: “What we did find an eloquent antidote to the agritech hard-sell based on deeply held values and an interest in technology that serves those values, but little to no interest in technology that does not. The farmers and growers we spoke to emphasised the importance of a more critical and context-specific approach to technological innovation, one that involved creating and evaluating technology based on its compatibility with agroecological principles and practices.”

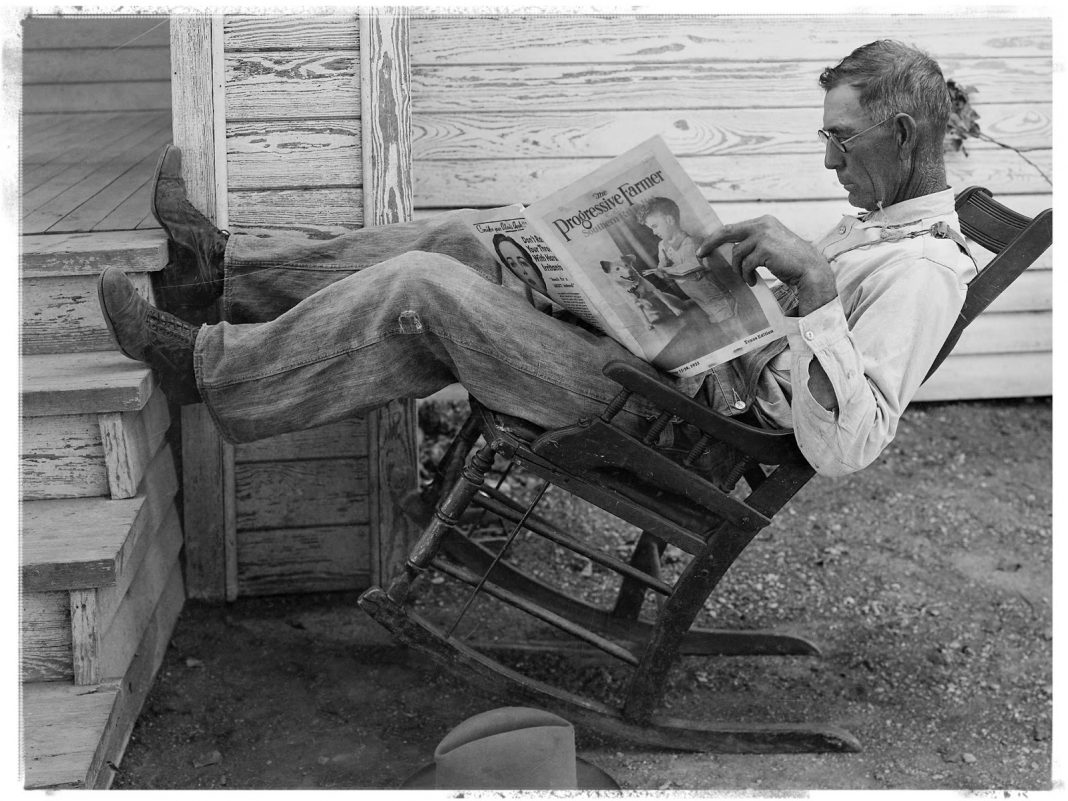

“Studying the Midwest Just Became Cool.” Caitlin Evans draws attention to the work of Jon Lauck and others in reviving interest in the study of the American Midwest: “According to a paper written by Paul Mokrzycki, when regional subfields of study took off in the mid-20th century, the Midwest was glossed over in favor of rising interest in the South and West. Since then, despite being America’s ‘heartland,’ the Midwest has remained ignored and overlooked as a region worthy of study. . . . Concerned about what this might mean for the future of the region — with the Midwest’s place in cultural discourse already declining — Lauck made it his mission to help revive the study of the Midwest.”

“Our Middle-Class Commune (Joint Bank Accounts, Noisy Sex and All).” Lucy Denyer talks with Elizabeth Oldfield about the joys and travails of living in community: “It is a radical thing to do — to commit not just to living with other adults once well past those traditional markers of adulthood, marriage and babies, but to put cold hard cash into a shared home with people you’re not related to or sleeping with. But the reasons that drove Oldfield and her husband will probably not sound unfamiliar to those who have faced a similar dilemma: how to afford to stay in a place when your family is growing, while also reducing some of the pressures of modern living.”