Abraham Lincoln burst into the office of his secretary, John Nicolay. “My boy is gone,” he sobbed. “He is actually gone.” The president turned and left the room. His eleven-year-old son Willie had just died. It was 5 p.m. on Thursday, February 20, 1862.

Willie had developed symptoms after a vigorous pony ride in a “chilly rain” two weeks earlier. The horse was a gift from his father. He rode it every day, whatever the weather. By February 5, the boy was sick with fever.

Lincoln was hosting a long-planned dinner the night Willie fell ill. Five hundred invited guests arrived to commemorate the First Lady’s refurbishing of the White House. The evening was a success for their callers, who stayed until 3 a.m., but the Lincolns were distracted and frequently absent. Lincoln and his wife Mary slipped away from the festivities in shifts so one of them could always be at Willie’s bedside.

Within hours, Willie’s eight-year-old brother Tad started showing similar symptoms. The younger boy ultimately recovered, but Willie, after enduring painful cramps and diarrhea, fell into a coma on February 18. He died two days later.

Weather did not cause Willie’s death. The brothers fell ill with “bilious fever,” now believed to be typhoid fever. This life-threatening infection came from their drinking water. The White House, like the rest of Washington, drew from the Potomac. The city’s population had grown from 60,000 to 200,000 that winter. Army camp latrines and ruptured sewage pipes soon contaminated the river.

“It is hard, hard to have him die,” Lincoln said in a choked whisper the first time he saw his son’s body. “I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so.” Elizabeth Keckly, Mary’s dressmaker, was tending the remains when the president walked in. She watched him lift the cover and gaze into Willie’s face. “I never saw a man so bowed down with grief,” Keckly recalled. “He buried his head in his hands, and his tall frame was convulsed with emotion . . . His grief unnerved him.”

The sight of Willie’s washed and dressed body in the Green Room stayed with Lincoln for years. The next Thursday, and many Thursdays after, the president sought seclusion in the room where his son had lain. He also spent a good deal of time in the stables with Willie’s horse. “The blow overwhelmed me,” he told a visitor. “It showed me my weakness as I had never felt it before.”

EARLY GRIEF

Lincoln was no stranger to death. A thoughtful review of the president’s many sorrows, informed by modern research, indicates that his grief was healthy, normal, and precisely what is expected after such an overwhelming loss. Years before Willie’s death, in the fall of 1844, Lincoln wrote a lament after visiting the graves of his mother and sister in southern Indiana. He sent the piece to Andrew Johnston, who published it in the May 5, 1847 issue of Quincy Whig under the title, “The Return.” Lincoln requested that the poem be published anonymously.

Oh! memory—thou midway world 'Twixt earth and Paradise, Where things decayed, and loved ones lost, In dreamy shadows rise.

In September of 1848, Lincoln took Mary and their two young sons, five-year-old Robert and two-year-old Eddie, to Niagara Falls. The grandeur of nature stunned Lincoln into a rare moment of rhapsody, calling the sight a “world’s wonder,” and adding, “Its power to excite reflection, and emotion, is its great charm. . . . It calls up the indefinite past.”

Two years later, on February 1, 1850, three-and-a-half-year-old Eddie died. “He was sick fifty two days & died the morning of the first day of this month,” Lincoln wrote his stepbrother John Johnston. “We miss him very much.”

The Reverend James Smith of Springfield’s First Presbyterian Church in Illinois conducted the funeral service. Soon Mary rented a pew and the couple began regular attendance. Lincoln rarely spoke of his son’s passing, but the loss changed him. “From the time of the death of our little Edward,” Mary wrote in 1870, “I believe my husband’s heart was directed towards religion.” Others too noticed the difference in Lincoln.

He was no longer “open souled,” according to his lifetime friend Joseph Gillespie. “If he had griefs he never spoke of them in general conversation. . . . He was tenderhearted without much shew of sensibility.” Mary understood this about her husband, commenting on the depth and breadth of his feelings. “[H]e was not a demonstrative man,” she said, “when he felt most deeply, he expressed, the least.”

In today’s therapy-conditioned society, we may mistake private, introspective mourning as unhealthy. Failure to talk out grief is seen as detachment, denial, or repression. This common misconception is out of touch with the last three decades of grief research and therapy. Experts have long acknowledged the complex nature of mourning. Physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and spiritual expressions are unique to each individual. Some people share their sorrow; others demonstrate their emotions in thought or action. These are not the signs of unresolved mourning that popular entertainment depicts. Many bereaved parents find solace in private, silent expressions of sorrow.

Lincoln’s reticence and contemplative reaction to grief could at times be vocal; at others it was demonstrated in changed behaviors. Ever after, according to his friend and bodyguard Ward Lamon, “He was a plain, homely, sad, weary-looking man, to whom one’s heart warmed involuntarily, because he seemed at once miserable and kind.”

ON TO THE WHITE HOUSE

On February 11, 1861, Lincoln and his sons Robert, Willie and Tad labeled their trunks: A. LINCOLN, THE WHITE HOUSE, WASHINGTON, D.C., and headed to the railway station. Well-wishers had gathered to see them off. “Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man,” he told the crowd. Even on this momentous day, Eddie was on his mind. “Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether, ever I may return.”

Mary joined them later. When the family was together in Washington, Lincoln and his wife settled on worshipping at New York Avenue Presbyterian Church. They first attended services on March 10 and were regular congregants throughout Lincoln’s presidency.

Robert was seventeen and soon left for Harvard. Tad and Willie were at home in the White House, where they hitched their pair of goats to chairs and carts to drive them through the halls, Tad crying “Get out of the way there!” to visitors and staff. They adored their father’s dog, Jip, who often sat on the president’s lap at lunch. Lincoln’s secretary John Hay described Tad as a “tricky little sprite . . . bubbling over with health and high spirits.” This displayed itself in endearing ways. The boys discovered a collection of calling cards in the White House attic. They immediately put on a minstrel show, using the historic artifacts to create a “snowstorm.”

Lincoln was indulgent with the youngsters. One visitor was shocked that while he spoke with the president, “his two little boys, his sons, clamored over legs, patted his cheeks, pulled his nose, and poked their fingers in his eyes, without causing reprimand or even notice.” This tolerant attitude might have been in reaction to Lincoln’s strained relationship with his own father, as well as the loss of Eddie over a decade before. One psychiatric study of thirty-seven bereaved mothers found that the participants thought “indulging in the little things” was fruitful and meaningful with their surviving children. Lincoln may have agreed. “It is my pleasure that my children are free—happy, and unrestrained by parental tyranny,” he said. “Love is the chain whereby to lock a child to its parent.”

Willie was the most like his father, “a peculiarly religious child,” his mother wrote, “with great amiability & cheerfulness of character.” The blue-eyed, good-natured boy enjoyed interacting with visiting royalty, playing with other children, or simply reading with his father. He was thoughtful, too, and savvy. When Tad busted a large mirror with a new ball, Willie promptly observed that there was more at stake than their father’s vanity. “It’s not pa’s looking glass,” he told his brother. “It belonged to the United States government.”

Willie’s observant nature displayed itself in other endearing ways. “This town is a very beautiful place,” he wrote of the hotel when he and Lincoln went to Chicago. “Me and father have a nice little room to ourselves.” He was also fascinated with railroad timetables and delighted in conducting an imaginary trip, with all the stops, from Chicago to New York.

“The most lovable boy I ever knew,” wrote sixteen-year-old Julia Taft when she met Willie, “bright, sensible, sweet-tempered and gentle-mannered.” Taft’s two younger brothers, fourteen-year-old Bud and twelve-year-old Holly, were inseparable from the Lincoln boys. When Willie slipped into a coma, Bud refused to leave his side. “If I go he will call for me,” he told the president.

A CHANGED MAN

Willie died less than a year after the Lincolns arrived in Washington. Tad and his mother were inconsolable for the first month after the loss. Lincoln spent time each Thursday in the room where Willie had lain, then paced in his private quarters, asking again and again why his son had to die.

Mary also wrestled with this question. “There are hours of each day,” she wrote, “that my mind, cannot be brought to realize, that He, who is considered, so great and good, a God, has thus seen fit to afflict us!”

These reactions are quite common with sudden, unexpected loss. Why did our loved one have to die? we may ask. Where was God when we needed him? Where is the justice? The grace? The mercy? Rabbi Earl Grollman said that such doubts are a healthy part of faith. Asking why, he wrote, is a howl of anguish and a natural reaction to pain: “The statement: ‘Dear God, why me? Why us?’ may be not only a question but your own normal cry of distress, a plea for help.”

Lincoln asked their minister, the Reverend Phineas Gurley, to conduct the funeral in the White House East Room. Before the service, Lincoln, Mary, and their son Robert asked to be left alone with Willie for a half hour.

Gurley’s eulogy was calm and compassionate. “We may be sure, — therefore, bereaved parents, and all the children of sorrow may be sure,” he said, “while they mourn He is saying to them, as the Lord Jesus once said to his Disciples when they were perplexed by his conduct, ‘What I do ye know not now, but ye shall know hereafter.’” The president asked for a copy of the sermon.

“I will try to go to God with my sorrows,” Lincoln said as the procession accompanied Willie’s body up the rise to Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown. His son was placed in a small chapel for a concluding prayer service and later moved to the Carroll family vault at the northwest end of the cemetery. Lincoln once confided to journalist Noah Brooks, “I have been driven many times upon my knees by the overwhelming conviction that I had nowhere else to go.”

The heartbroken father frequently visited his son’s tomb and twice had the crypt opened so he could see Willie again. This may strike modern readers as disturbing or morbid, but it was in fact an act of grieving love, according to John Updike, who added, “Our ancestors looked gravely and steadily upon things that we cannot.”

In Lincoln’s day, bodies were not hastily removed by discreet morticians. Open coffins were the norm, usually resting at home until the burial service. Pictures of corpses, dressed in their finest clothes, were commonplace and “make up the largest group of nineteenth-century American genre photographs,” observes Stanley Burns, professor of Medical Humanities at New York University. In our time, these mourning rituals might seem unhealthy, but it may be that we have lost something valuable. “The piety of the previous century,” Updike concludes, “clung to the Christian tenet, unemphasized in today’s churches, that the body is the person, with a holy value even when animation ceases.”

Lincoln took to re-reading Gurley’s eulogy in his darkest moments of grief. “There was something touching in his childlike and simple reliance on Divine aid,” Brooks wrote of this period, “especially when in such extremities as he sometimes fell into.” Tad was also prone to extremes after his older brother passed. He was both “a prematurely serious and studious child,” Hay wrote, and something of a tyrant in the White House. Mary, who was bedridden for three weeks after the death, dressed in mourning for a year. She noticed her husband’s views on an afterlife began to change.

SPIRITUAL CONCERNS

Mary invited Francis Vinton of Trinity Church in New York to the White House. The president welcomed his visit. “Your son is alive, in Paradise,” Vinton assured the couple. “Alive!” Lincoln moaned. “Alive! Surely you mock me.” Yet the rector’s thoughts on Luke 20:38 (“For he is not a God of the dead, but of the living: for all live unto him”) resonated with grieving father. He asked for a collection of Vinton’s sermons.

Mary felt this was an important turning point in Lincoln’s spiritual life. “When too—the overwhelming sorrow came upon us,” she wrote, “Willie was called away from us, to his Heavenly Home, . . . he [Lincon] turned his heart to Christ.” Most biographers agree, chief among them Ida Tarbell, that Lincoln became a believer after Willie’s death. Tarbell suggests that this experience caused the president “to look outside of his own mind and heart for help to endure a personal grief.” Perhaps, in a way.

Mourners often give priority to finding meaning in their lives. Researchers and therapists note that parental bereavement frequently opens paths to transformation and growth that include a surprising list of coping methods: new appreciation of life; recognition of life’s transience and frailty; closer relationships; valuing others; personal strength; humility; a feeling of being fully present; and a marked spirituality. “I had a good Christian mother,” Lincoln told Rebecca Pomeroy, an army nurse dispatched by Dorothea Dix to take care of Mary, “and her prayers have followed me thus far through life.”

One day Lincoln asked Gurley to join him an hour before breakfast at the White House. “We have talked about the soul after death,” the pastor told a friend that same day. “That is a subject of which Mr. Lincoln never tires.” The president began attending weekly prayer meetings at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church. He preferred to sit in the pastor’s study with the door ajar. This practice, he told Gurley, provided spiritual solace shorn of ostentation or unwanted attention.

Such private mourning can be surprisingly helpful. Mental health counselor and poet Miriam Greenspan insists that our dark feelings hold within them kernels of emotional well-being. “We need to honor three basic emotions that are an inevitable part of every life: grief, fear, and despair,” she writes. Such feelings are not negative in themselves, but we may deal with them in negative ways. In his rare moments alone, Lincoln faced the reality of his loss and the spiritual pain of grief. “Ever after there was a new quality in his demeanor,” observed artist Alban Jasper Conant, who painted Lincoln’s first portrait, “something approaching awe.”

Lincoln lavished attention on Tad and was careful of Robert’s safety. This irritated the young man, who insisted that he should enlist and do his part in the war. Lincoln finally relented and secured a nominal rank and position on General Ulysses S. Grant’s staff.

The president gave few signs of sorrow during the daily duties of his office, Hay noticed, but all the while “was profoundly moved by this death.” In the spring of 1862, English journalist Edward Dicey also observed: “You cannot look upon his worn, bilious, anxious countenance and believe it to be that of a happy man.”

DREAMS OF WILLIE

In May, 1862, Lincoln visited Fort Monroe in Virginia. He asked General John Wool if he might borrow a copy of Shakespeare’s works. After reading for a few hours, Lincoln asked Colonel Le Grand Cannon if he might share a few selections with him. The president recited from Macbeth and King Lear. Then he read a passage from King John, written shortly after the playwright’s son, Hamnet, had died. Lincoln’s voice began to shake.

Grief fills the room up of my absent child, Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me, Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words, Remembers me of all his gracious parts, Stuffs out the vacant garments with his form. Then have I reason to be fond of grief.

When Lincoln finished the verse, he set his book aside. “Did you ever dream of some lost friend, and feel that you were having a sweet communion with him, and yet have a consciousness that it was not a reality?” he asked. “That is the way I dream of my lost boy Willie.” The president then broke down into convulsive weeping, as did Colonel Cannon.

Lincoln had what is known as a lucid dream, during which we are aware that we’re dreaming. This is not unexpected. In fact, it can be quite healthy. These dreams are not easily dismissed as hallucinations nor are they readily accepted as spiritual visitations. In either case, it is clear that they provide insight into the emotional impact of death and the mystical union it inspires.

Dreams of our dead reflect a deep need for spiritual union after a loss. They facilitate adjustment to the death by helping us process trauma and understand the many complex emotions of mourning. These grief dreams, as researchers refer to them, have a connection to our spiritual awareness of self in relation to others. They often awaken a growing sense of compassion while also serving as a coping mechanism.

The president had a lifelong interest in dreams and their possible meaning in the waking world. “Think you better put ‘Tad’s’ pistol away,” he once wrote to Mary in June, 1863. “I had an ugly dream about him.” Mary also had recurring dreams of their son. “Such a dream as I had of my idolized Willie, last night,” Mary wrote in 1869. “Some day I will tell you all.”

MARY’S BROKEN HEART

In July of 1862, Mary took a short trip to New York and Boston. The joy she felt in the sights naturally brought Willie to mind: “Yet, in this sweet spot, that his bright nature, would have so well loved, he is not with us, and the anguish of the thought, oftentimes, for days overcomes me.”

In the first extremity of loss, during the period counselors call acute grief, Mary felt she experienced Willie—and occasionally Eddie—standing at the foot of her bed. The boys seemed happy and loving. This led her to mediums. In an effort to be supportive, Lincoln accompanied Mary to two séances: one in Georgetown; the other in the White House.

A disheartening number of biographers have subjected Mary’s obvious emotional distress to ridicule, inserting snide comments, or presenting her in an unfavorable light. I might have done the same before my daughter died. But grief research paints a different picture.

Bereaved adults show increased corticosteroid activity during the first few years after a death. In some cases, this can result in psychiatric difficulties, which in turn can lead to exhaustion, stress, and diminished immunocompetence. It occurs to me that before we judge Mary’s reactions, we might consider that few of us know how we might respond to losing two children. Sorrow is unique for each mourner. Mary dealt with loss in her own way, as did her husband. “Be aware of the general picture of grief,” psychiatrist M. Katherine Shear advised caregivers, “but try not to have preconceived expectations about the specific constellation of symptoms or their time course.”

Time is important in understanding Mary’s grief. “It is impossible, for time, to alleviate, the anguish, of such irreparable losses—” Mary wrote in 1865 after Lincoln’s assassination, “only the grace of God, can calm our grief & still the tempest.” Four years later, in 1869, she admitted to a friend, “Time brings to me, no healing on its wing.”

It is easy to dismiss such thoughts as the complicated grief of a widow and bereaved mother that refuses to “move on.” Nothing is further from the truth, according to sociologist and death studies pioneer Geoffrey Gorer. Parental bereavement, Gorer observes, is “the most distressing and long-lasting of all griefs,” adding that “it seems to be literally true, and not a figure of speech, that the parents never get over it.”

THE LINCOLNS’ COMPASSION

On February 20, 1863—one year after Willie’s death—Mary Jane Welles sat with the First Lady on what she knew was a difficult day. Wells and her husband, Gideon, the Secretary of the Navy, had lost six children, including young Hubert, who had died in November, 1862. Mary thanked her visitor, adding, “Only those, who have passed through such bereavements, can realize, how the heart bleeds at the return, of these anniversaries.” Mary’s use of the word realize deserves attention.

During and after the American Civil War, thousands of people wrote they could not quite realize the deaths of their loved ones. The term meant, in essence, that they could not “make it real” in their minds. “When I can bring myself to realize that he has indeed passed,” Mary wrote of Willie on May 29, 1862, “my question to myself is, ‘can life be endured?’” Seven months later, on December 16, she wrote that her grief was not lessened, but the finality of her loss was brought home to her: “My precious little Willie is as much mourned over & far more missed (now that we realize he has gone).”

Lincoln too used this familiar expression. “You can not now realize that you will ever feel better,” he wrote to twenty-two year old Mary Frances “Fanny” McCullough when she lost her father in December of 1862. For Fanny to experience life’s joys on some distant day, Lincoln wrote, she must also realize, or make real, her current sorrow. Then, Lincoln assured her, “The memory of your dear Father, instead of an agony, will yet be a sad sweet feeling in your heart, of a purer, and holier sort than you have known before. . . . I have had experience enough to know what I say.”

The Lincolns’ attention to kindness in the wake of their son’s death is another common characteristic of those who grieve. Studies show there is a sense of transcendence or transfiguration in the hearts of many bereaved parents: in their search for meaning they turn outward, commiserating with the suffering of others. “Grief itself is a bridge that reminds us of our shared human capacity for love and comfort,” observed respected grief experts Robert Neimeyer, Darcy Harris, and Gordon Thornton. This isn’t always easy.

Mary admitted that she shied away from missives that recalled the pain of losing her son. But when Hannah Shearer’s eldest son Edward died in November of 1864, Mary was prompt to take up her pen. “Now, in this, the hour of your deep grief, with all my own wounds bleeding afresh,” she wrote her friend, “I find myself, writing to you, to express, my deepest sympathy, well knowing how unavailing, words, are, when we are broken hearted.”

Lincoln also found himself reaching out to others. In 1864, he invited sixteen-year-old sculptress Vinnie Ream to the White House for a five-month series of sittings. Willie would have been thirteen at the time, and the president seemed to enjoy the artist’s company. “I made him think of Willie,” Ream recalled. “He often said so and as often wept.” The time was not wasted. Ream’s sculpture of Lincoln was to be hailed as “one of the best literal representations” of the president.

The next year, on April 10, 1865, fire broke out in the White House stables. Lincoln rushed to the burning barn, calling for help. Security guards physically pulled him away from the conflagration. One of the guards, Robert McBride, came upon Lincoln weeping in the East room as he watched the fire. Tad then explained that the stable housed Willie’s horse. “The thought of his dead child had come to his mind,” McBride wrote, “and he had rushed out to try to save the pony from the flames.”

CARE FOR A NATION

Lincoln’s compassion displayed itself in other ways. “I am satisfied that when the Almighty wants me to do or not to do a particular thing,” he once said, “he finds a way of letting me know it.” By July of 1862, five months after Willie died, the president was speaking of emancipation.

This was not unexpected. Lincoln’s views on slavery were well known. But the suddenness of his announcement, after the Confederate retreat at Antietam, shocked his cabinet. “He had made a vow, a covenant,” wrote Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles on September 22, 1862, “that if God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of Divine Will, and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation.”

The president candidly shared his reasoning with others. “When Lee came over the river,” Lincoln wrote Massachusetts congressman George Boutwell, “I made a resolve that when McClellan drove him back . . . I would send the Proclamation after him.” Later, he explained to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase the seriousness of his decision: “I made a solemn vow before God that if General Lee was driven back . . . I would crown the result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves.”

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued less than a year after Willie’s death: January 1, 1863. That same day the White House held its first public reception since the boy’s passing.

Eleven months later, on November 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered his famous address at Gettysburg. He nearly didn’t go. Two days earlier Tad had again fallen seriously ill. Lincoln and Mary were distraught, reminded of Willie’s death, but the president felt strongly that he must make the trip. A methodical man, Lincoln wrote a draft of his speech at the White House with his usual thorough edits. He made the six-hour journey to Gettysburg on November 18 and stayed at the home of David Wills.

Lincoln rose early the next morning. He was slotted to deliver brief dedicatory remarks for the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, following the afternoon’s main oration by Edward Everett. The president spoke no more than three minutes, his high Kentucky tenor easily carrying to the closest of the twenty thousand spectators. As with his views on emancipation, the president’s thoughts on American national purpose had for years been leading up to this point. Still, even today we are stunned by his compassion and resolve. Lincoln’s search for meaning had raised him to new heights of eloquence.

“FOREVER REUNITED”

Good Friday, April 14, 1865, seemed full of hope. Lincoln woke, read a few pages of the Bible, as was his habit, and breakfasted with Robert, now a captain in the Army. He later related to his cabinet a recurring dream that he’d had the night before. He felt he was floating on a phantom ship across a vast expanse to an uncharted shore. This dream, Lincoln said, was invariably followed by some important change or disaster. Nicolay and Hay described the president as “singularly happy.”

Around 5 p.m., Lincoln and Mary took a carriage ride. Two days earlier, on April 12, General Robert E. Lee had completed the infantry surrender ceremony that formally ended hostilities. “Mary, I consider this day, the war, has come to a close,” Lincoln said. They were in good spirits and yet, as with many bereaved parents, their dead son was not far from their minds.

“We must both, be more cheerful in the future—” Lincoln said. “between the war & the loss of our darling Willie—we have both, been very miserable.” They rode together in comfortable silence, then he added, “I have never felt so happy in my life.” Mary was shocked. “Don’t you remember feeling just so,” she said, “before our little boy died?”

That night Lincoln was struck by an assassin’s bullet. He died on April 15, 1865. Tad, barely twelve years old, wept openly when he saw his father’s body two days later. “I can hardly believe that I shall never see him again,” he told his nurse. “Well, I will try and be a good boy, and will hope to go someday to Pa and brother Willie, in heaven.” Tad died of tuberculosis on May 18, 1875, at the age of eighteen.

Mary wore black for the rest of her life. “When I reflect, as I am always doing,” she wrote in November of 1865, “upon the overwhelming loss, of that, most idolized boy, and the crushing blow, that deprived me, of my all in all in this life, I wonder that I retain my reason & live.” Later Mary turned away from the desperate measures of spiritualism, instead thinking of her dead son as “my Angel boy, in Heaven,” and waiting, she wrote, “to be rejoined to my dearly loved ones, who have ‘gone before.’ . . . to be forever reunited to my idolized husband & my darling Willie.”

On April 21, 1865, Willie’s casket was disinterred to accompany his father’s coffin on Lincoln’s funeral train to Springfield, Illinois. They rode together on the sixteen-wheel coach that had been built to transport the Commander in Chief to battlefields during the war. Six other cars carried mourners, with one more reserved for a military honor guard.

Today Willie rests with Eddie, Tad, and his parents in the Lincoln Tomb at Oak Ridge Cemetery.

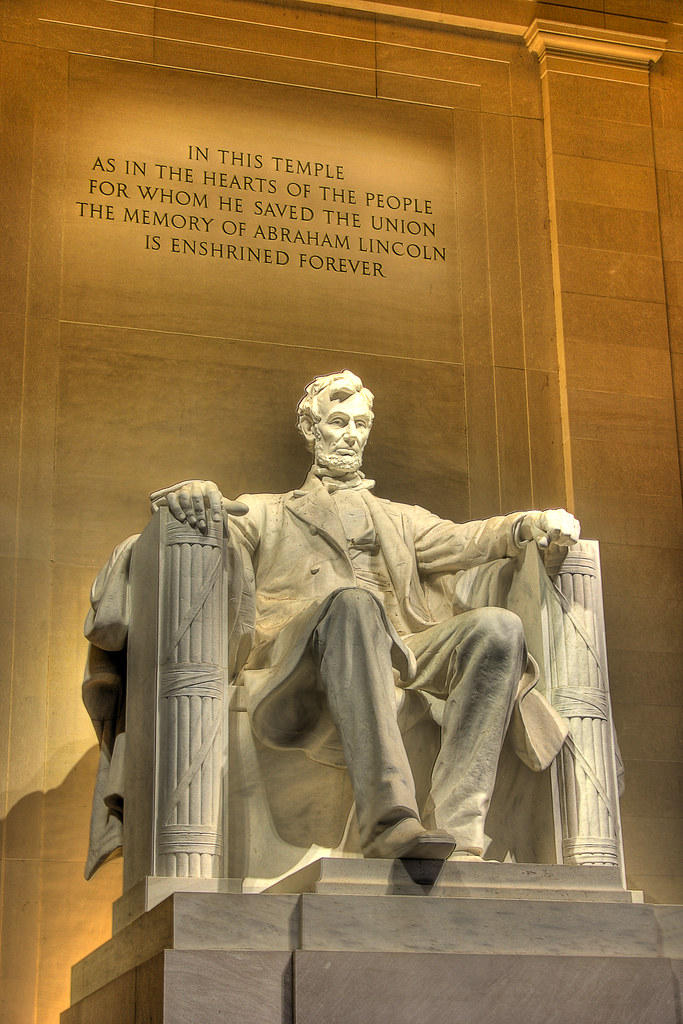

Image via Flickr