One day, rummaging around the house for something to read, I came across a book I couldn’t remember purchasing or even seeing before. It belonged to the Penguin Modern Classics series, its grubby cover misaligned with the brittle pages and featuring a dull portrait of a woman in a hat. When I opened the unpromising volume, the spine cracked, showering me with glue particles. The book was called The Rector’s Daughter, by F.M. Mayor, and was first published in 1924. A glance at the back cover confirmed that the novel was indeed about a middle-aged woman and her clergyman father. As I began reading, and the book slowly disintegrated in my hands, the thought crossed my mind that if I liked this novel I could write something to mark its centenary.

People almost always refer to The Rector’s Daughter as “neglected,” “forgotten,” or “lost.” It’s one of those books that have become famous for being obscure. As the story opens in the “insignificant” English village where Canon Jocelyn and thirty-five-year-old Mary spend their days, George Eliot and Anthony Trollope inevitably come to mind. Kindly churchmen pursue their scholarly interests, while the townspeople keep up a sleepy round of tea parties, festivals, and visits from the Bishop. Yet not only did The Rector’s Daughter appear in 1924, in the heyday of Ulysses, The Waste Land, and Mrs. Dalloway, it was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. The novel might feel Victorian, but it derives at least in part from Modernism, and Cambridge-educated Flora Macdonald Mayor was no backward villager but an informed observer of her time.

Rather than writing in a Joycean stream of consciousness, or splintering her story into Cubist fragments, Mayor treats her familiar setting with a dry, gentle satire. Few tourists would go out of their way to visit Mary’s isolated village, she writes: “Still, being damp, it was bound to have certain charms; the trunks were mossy, and the walls mouldy.” A family’s drawing-room is furnished and appointed like “a kind of temple dedicated to boredom.” An Anglican clergyman reads the Bible to a Dissenting shut-in, who responds “as if it were her special book, read by her permission.”

Beloved and taken for granted, the rector’s daughter seems as much a permanent fixture as the trees and houses, caring for her invalid sister and performing a host of parish duties. At one point, beginning to chafe at her lonely life, she indulges in some alarming thoughts, imagining a world that accommodates her desires. As the narrator remarks, “The spirit of the times was making itself felt in her.” The assertion, at once oracular and ambiguous, recalls a similar, more famous pronouncement from Hawthorne: “The scarlet letter had not done its office.” Like Hester Prynne, who embraces her punishment with defiance and sorrow, Mary Jocelyn finds the spirit of the times both liberating and corrosive, raising new possibilities while undermining her conscience and her long-held sense of self.

For the first third of The Rector’s Daughter, Mayor depicts Mary’s dreary life with her father, who indulges his snobbish devotion to the classics while denying Mary love, self-expression, and even simple recreations like tennis. She knows she’s being buried alive, but she accepts it as her lot. When a new vicar arrives in a nearby town, the man seems nothing short of a godsend. Robert Herbert is bookish, shy, and ordinary-looking at best—exactly Mary’s type. Stunned and overjoyed, the two introverts fall in love. Then Mayor springs the first big surprise of the novel.

The vicar goes away on a visit, and after a suspenseful wait Mary hears from him. At first she misreads the letter, unable to register its contents. Herbert has become engaged to a shallow, wealthy, drop-dead gorgeous huntswoman who once snubbed Mary at a party. As Mary exclaims of Kathy Hollings, in quintessentially English fashion, “I believe the county are the vulgarest people in the world.”

Herbert’s “infatuation” with Kathy soon wears off, and everyone—Herbert, Kathy, Mary, family and friends—concedes that the marriage was a “mistake.” Kathy runs off to the Riviera, leaving Herbert and Mary to re-kindle their impossible love. One scene, one kiss, conveys the intensity of their passion. The story seems headed down a predictable path, but another surprise awaits.

In Sebastian Faulks’ 2001 novel On Green Dolphin Street, a married woman who is having an affair “had always believed that the adventure of marriage was incomparably more interesting than the petty indulgence of betrayal.” Marriage might be interesting, but it fails to hold Mary van der Linden, and at a crucial moment she chooses the affair. For Faulks, his protagonist’s belief is a hypothesis to be tested and challenged. In The Rector’s Daughter it is axiomatic.

After the kiss between Herbert and Mary, the main characters stand at a painful juncture. Herbert and Kathy, grotesquely ill-matched, face at best a loveless truce, while Mary, timid and awkward though she might be, poses a powerful outside temptation. Yet just when a forbidden romance between Herbert and Mary seems imminent, Mayor reveals a tender side of Kathy and hidden, hopeful aspects to her relationship with Herbert.

After a century of novels like On Green Dolphin Street, many readers might be disinclined to take Mayor’s word for it. How can these two incompatible people make their marriage work? Why bother trying? It was a mistake. Just undo it. Mayor doesn’t moralize in response to such objections, or explain why Herbert and Kathy ought to stay married. She doesn’t rebuke the spirit of the times. She simply treats the couple’s love as an established fact, which might be harder for readers to accept than if the characters simply stuck it out in faithfulness to a solemn vow.

We’re shocked when Herbert and Kathy marry, and even more shocked when their marriage endures, because we’re confronted by how little we know them. And if we don’t know them, we might not know the real people around us. Some novels create the illusion of characters whom we understand better than we understand our own friends and family. The Rector’s Daughter makes us question how completely and reliably we can know anyone. Far from being a bleak or shattering thought, this chastened awareness is fresh and exhilarating, transforming our companions from objects of knowledge into occasions of reverent wonder.

Long after their infatuation runs its course, long after the forbidden kiss with Mary, Herbert and Kathy begin to glimpse what keeps them together: “Habit helped them. It helped Mr. Herbert, for instance, to get on with Kathy’s jokes; not to listen to them, but to listen to her ringing laugh, which to his ears was one of the pleasantest sounds in Nature, not musical, but delightful, like the cawing of rooks.” The comparison might not be very romantic, but that seems to be Mayor’s point. When the angels stop singing, the rooks go on cawing, and the grateful cleric discovers he liked the rooks all along.

Toward the end of the novel, Mayor’s sensitive portrayal of the Herbert marriage almost overshadows her title character. Mary slips into the background, becoming again the quiet, self-effacing spinster. Yet as Kathy and Herbert enter more deeply into each other’s confidence, Kathy learns she must share her husband’s affections with Mary, and that she and Herbert have barely glimpsed all the grace and tact they’ll need.

Perhaps this novel remains little-known because it so often rebuffs our expectations and resists our usual categories. It’s neither Victorian nor Modern, sentimental nor tough, nostalgic nor avant-garde. It doesn’t preach traditional morality, nor does it subvert it. Eloquent and nuanced, never pompous, The Rector’s Daughter sets before us the inexhaustible mystery of persons and the ways they manage to live together.

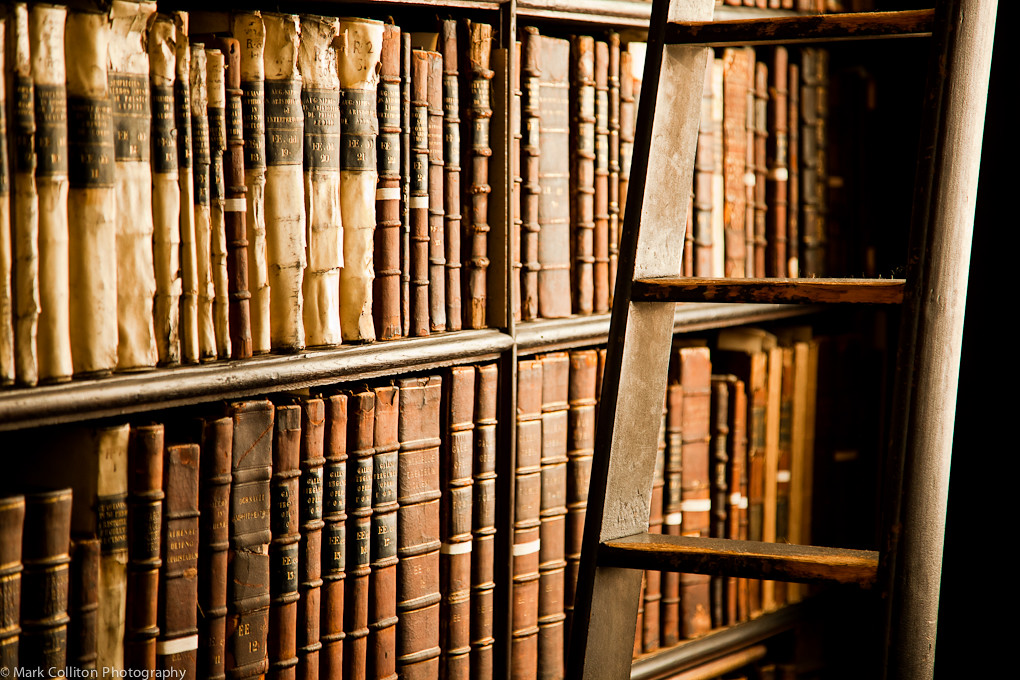

Image via Flickr

David’s review was more than a review for me. I have tried twice to find this novel, and it is very hard to come by. But David’s very wise and perceptive words about this novel have just made sure that I will now pull out all the stops, and thus I am sure I will come into possession of this novel. Thank you to David for bringing this novel to my attention many months ago, and, with his sensitive, perceptive writing now, making sure I too would become a reader of this novel.

Hello Mel — there are lots of copies available on bookfinder.com, and at good prices too.

When I read this review I thought I recognized her name, so I looked her up on wikipedia. Turns out that she wrote some ghost stories that were praised by M.R. James, collected in a book called ‘The Room Opposite.’ I have quite a few collections of English ghost stories, and I’m sure her work appears in some of them, but I don’t think I have a copy of the book itself.

Comments are closed.