There’s a simple thing I’ve observed while hiking. As you struggle uphill toward the crest of a mountain pass, your mental and physical energies are focused on every step. Then at the crest, just as you are beginning your descent on the other side, there’s a physical and mental release, yielding an expansion of consciousness and clarity of thought. I hope readers will test this for themselves and report back.

That clarity of thought is what happened to Friedrich Froebel as he and fellow educators walked over a mountain pass in the Thuringian Forest in about 1840. Froebel had been at work developing his methods of early childhood education, a long pathway uphill of one foot ahead of the other. At the crest of the mountain pass, he exclaimed to the others, “Eureka! I know now what to call my youngest child.” The name he next exclaimed was “Kindergarten,” a word and a methodology that temporarily reshaped education in the US and around the world. It may seem obvious to most, but the name means a garden of children, conveying the sense that children grow just as a seed might grow in a well-tended garden. Provide light, nourishment, and water at the right time, and patterns inherent in the child lead forward in growth.

With Froebel and his approach largely forgotten, kindergarten has become for so many educators in the US, “the new first grade.” In an earlier time, however, there was a push to turn the rest of education toward the model of learning and child development that Froebel’s Kindergarten offered.

Kindergartens began in the US as early as the 1850s, but the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition provided the opportunity for Kindergartners to show off their methods of education to a nation hungry for educational reform. Nina C. Vandewalker described this in her book, The Kindergarten in American Education (1908):

The Exposition kindergarten was conducted in an annex to the Woman's Pavilion, by Miss Ruth Burritt of Wisconsin, who had had several years of experience as a primary teacher before she became a kindergartner, and whose manner and insight were such as to gain adherents for the new cause. The enclosure for visitors was always crowded, many of the on-lookers being "hewers of wood and drawers of water, who were attracted by the sweet singing and were spellbound by the lovely spectacle." Thousands thronged to see the new educational departure, and many remained hours afterwards to ask questions.

Kindergarten was a striking departure from rote learning, harsh discipline, and the ruler-slapped knuckles common in schools at the time. But pendulums swing one way and then the other. And perhaps it is time for Froebel’s Kindergarten to lead the way back.

Parents have always been deeply concerned about the success of their kids, though perhaps never as anxious as they are today. Having been sold a bill of goods about the value of standardized testing, they’ve become obsessed with measuring their own children’s performance relative to others, ignoring the fact that each child progresses in a variety of developmental areas, at their own pace. With reading and math being the primary obsessions, Kindergarten has in many instances become just another year in schooling in which children are measured and compared in a game of one-upsmanship in which none win.

A simple example is the age at which a child begins to walk. When your child is walking at 9 months, the pediatrician will assure you that’s normal. If a child waits until 13 months, the pediatrician will tell you the same thing. But when it comes to reading, parents and teachers alike are concerned if a child is not at “grade level” or reading in Kindergarten or first grade at the very latest. Parents should be assured at the very least that in reading and so many other things, children are not clockworks and will mature in myriad ways at their own pace. Readiness to read is not a thing that arrives for all children at the same time.

Froebel had other developmental concerns in mind. As a very young child his mother died. His father remarried and at first young Friedrich was the apple of his stepmother’s eye. Then her own children came, and young Friedrich was virtually abandoned to be raised in the streets. Being deprived of mother’s love himself, he became observant of the love German mothers bestowed on their children.

Being a poor student in school he was farmed out to the care of an uncle and apprenticed to a forester, taking care of the forest while also becoming acquainted with those who earned their livelihoods from the woods. In the Thuringian forest he picked up the habit of whittling wood, and one of his most ardent proponents, Baroness Bertha von Marenholtz-Bülow, claimed to have in her possession small, wooden, hand-carved objects given her by Froebel. Those small hand-carved objects in the days before power tools made woodworking easier and fast, likely provided Kindergarten and the world with its first instructional toys.

Before becoming an educator Froebel had worked in the laboratory of Christian Samuel Weiss sorting and classifying specimens in his vast collection. Weiss was an internationally known expert in minerals and crystallography. Working with those crystals seemed to have had an effect. Froebel’s educational methods included some of the first toys designed for early childhood education. These systems of blocks, which he called “gifts,” were to be delivered to the children a set at a time.

Trained kindergarten teachers were to help guide the child’s exploration of these “gifts.” And it was noted that they would be used in several ways. One way was to create “forms of knowledge” by exploring numbers, mathematic concepts, and physical principles. A second way was to explore “forms of Beauty” creating pleasing and expressive forms that were reflections of the universal order that Froebel had discovered in the laboratories of Christian Samuel Weiss. The third way the gifts were to be used was in creating shapes and forms representing relationships and objects from the child’s own life. A fourth thing that both teachers and parents would appreciate was that each gift came in a wooden box in which the gift would be returned and put away at the end of play.

But there was a lot more to Froebel’s kindergarten than the gifts which soon took on a mystical air among some educators. As a garden of children, the children gardened and tended small animals. As members of communities, children were constantly on the move outside the classroom, becoming familiar with local trades and with nature — for his time in the Thuringian forest gave Froebel a profound interest in the natural world and all the things and people interconnected within it.

In the highly fractured society we live in today, enabling our children to find their own place within the larger scheme of things should be the primary goal, not just in Kindergarten and preschool, but in the whole of education.

Taking two German terms—Glied, meaning member, and Ganzes, meaning whole—Froebel combined them in the word Gliedganzes meaning “member whole.” His concept reflected his understanding of life and set the goals for his system of education. Gliedganzes recognized that each child is a whole and unique form and simultaneously inter-connected and inner-connected as a functional member within the worlds of nature and of man.

Froebel published a book of songs with illustrations (Mutter- und Kose-Lieder translated in English as Mother Play) to inspire German mothers to take a greater and more coherent role in their child’s education and preparation for life. Among the illustrations Froebel published in that book was one of my favorites, the Charcoal Maker.

Many times, as a forester’s apprentice, Froebel would have encountered charcoal makers, who played an important role in the German economy but who would be filthy and frightening to kids. Froebel celebrated the charcoal maker with an illustration of his hut and burning pile, both in the form of teepees of wood. The illustration showed a child’s hands forming the teepee shape as children would do as the song would be sung, and it also showed the blacksmith at work with his hammer, anvil, and charcoal forge, and a mother feeding her child by the warmth of a charcoal stove. For me, that illustration serves as an illustration of the inter-connectedness that Froebel hoped his system of education would offer.

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about Froebel’s Kindergarten was its recognition of the value of play. Just because someone is at play certainly does not mean they’re not working hard at learning. And that’s a lesson we’d best all learn. My mother retired from teaching Kindergarten in a mixed-race community in Omaha, Nebraska. When she would have parent/teacher conferences with a new parent, she would advise that “When your child comes home at the end of the day and you ask, ‘what did you do today?’ and your child answers ‘play,’ that’s the right answer.” If you understand that a child’s growth comes from a spark within, just as does the growth of a flower, a crystal, or a mighty oak, you might take a more trusting view of a child’s growth. And we’d all benefit by urging our schools to do the same.

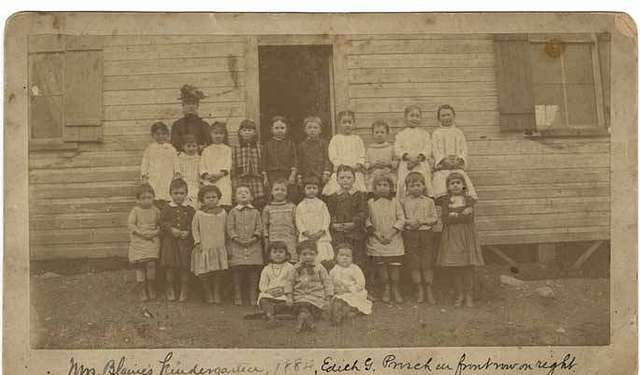

Image via Picryl