It’s the spring of 1864 just north of Shreveport, Louisiana and a man has come home from the war. His wife, a sweet young woman named Phobe, has prepared a pot of beans to be enjoyed alongside cornbread and sun tea. Chicory coffee steams in a small cup in her hands, and a tear wells up in one eye when she sees that charming, chiseled man with strawberry blonde hair, a bit longer now than the last time she saw him. They share a hug and a kiss or two before sitting on the porch together for a smoke and breakfast in the Louisiana fog.

“George,” began Phobe, “how long till you go back again?” The question lingered, and he told her not to worry her pretty little head about that. He’d go back in a few days, he told her, stroking his recently re-grown whiskers. Well whereabouts George? Where this time? Yanks are all around here’s what they’re sayin’ in town. She was scared easy, and George’s typical Smothers aloofness was no consolation.

“I’ll be in Missouri again ‘fore long, my dear, and I’ll think of you ever’ night and day,” he’d say.

A few days pass and he’s gone again, a few homemade apple butter sandwiches in his pack along with a new love letter from Phobe. She wrote him religiously. Not all of it’s a lie, he thought. He was going to Missouri, and he was fighting in the war. Confirming he was out of his wife’s sight, he checked deep in his pack to make sure his other uniform was there: his Union blues. And beneath the Prussian blue coat and the sky-blue trousers, down at the bottom stuck cross-ways into the seam and covered by a Bible was another letter. This one older and torn at the edges, bearing marks of having been read and re-read, bore another name.

"G.W., my mountain man, won't you come home to me in St. Louis? Yours forever, Zanie"

My late grandmother passed down a much simpler, less dramatic telling of this tale to me long ago. I’d ask her on occasion to tell me a story about our family, and this one came to the surface of her endless memory more often than any other. And so I’m pleased to share this tale as an example of family story-telling: the tale of George Washington Smothers. To do it justice, I’ve got to tell you about Nanny first.

My late grandmother was at once remarkable and expected. Predictable yet curious. “Nan” or “Nanny” is what I called her. Nan fried eggs and bacon for my grandfather just about every morning while he perused the funnies. She’d poke her head out of the kitchen doorway to fuss at him for laughing too loud or for cussing in front of me, and then go back to singing or humming or being silent. Her silence was as joyful as the tunes she carried, though. Nanny cooked and cleaned and sewed; Nanny raised three kids and put up with their father. (They were more or less happy in their 53 years of marriage.) On at least one occasion she bailed him out of the county jail in Magnolia, Arkansas for illegal street racing. She was like many other women of her time and place: longsuffering, dutiful, selfless, endlessly compassionate. Like any good Celt she had a knack for memory. Never bending the knee to Rome, her people also never adopted the habit of writing down their history. So she remembered things. Nanny worked hard and raised kids and prayed. Oh boy did she pray. Shortly before she died, I was able to ask her one final time about some of our stories. This one came up. George Washington Smothers fought on both sides of the Civil War not because he was a spy for one side or the other but because he had a wife on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. I’m sure I wrote some of it down, but I just as quickly lost the paper as I committed some of what I’d written to memory. It’s a Celtic urge to memory. Or maybe this is my excuse for the classic Smothers aloofness. Nanny died in late April of 2020 in the middle of the night amid two weeks of near constant rain. Hers was a peaceful passing, although not devoid of pain. She died in the night. Rain came down in sheets. That day when I walked in the door, I saw family I hadn’t seen in years. My Uncle Jimmy has in some ways continued to be the storyteller of my family. If my dad or I have any ancestry or local history questions, we send them his way. He’s not getting any younger, though. Good education is wasted on the young, the saying goes, and perhaps part of the reason is that the young don’t expect that good things might simply cease. A recent health scare with my uncle made me realize that our stories, our memories, might simply cease if I don’t do what Nanny did: Love my people with my memory.

Yet failing to tend the lineage of family memory isn’t just a problem that afflicts the typical aloof Smothers; it is rampant among people my age. People in their twenties lose their grandparents, their more elderly aunts and uncles, and their childhood pets. They lose ties to their local communities quite easily, too. Moving away for university and not coming back often or at all is considered “success” in our moment. But it’s not success. It’s a kind of death.

The war ended in April of 1865, but to some it had just begun. The country was reunited. Many men on the battlefields could return home. They could rest, tend their fields, milk their cows. After all, who would want to keep warring after Appomattox? Apparently those idealists who never raised a finger in battle. Those men bold enough to take a side, yet too cowardly to take up arms. Men like John Wilkes Booth.

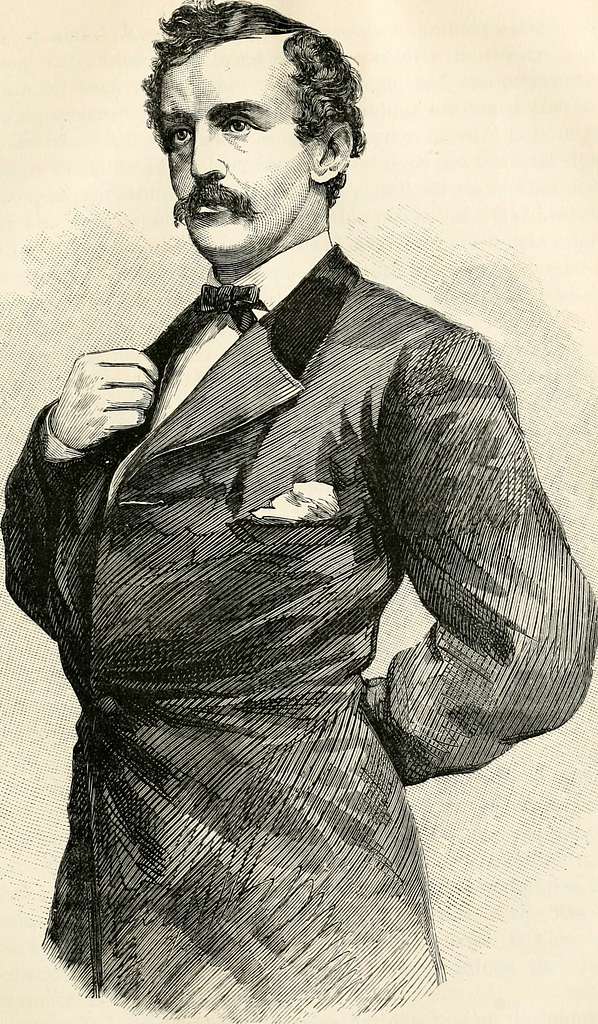

John Wilkes Booth was an actor from a line of actors and parliamentarians if you look back far enough. A home lacking parents for long stretches fostered a cruel loneliness in the young Booth. Ditching school and shooting neighborhood cats to near extinction became his subjects. Then he became a young man.

The last thing a boy with bad character needs is for a bunch of girls to fall head over heels for him. It’s unclear exactly when Booth realized he was a hunk. Like a dolled up General Custer, he ruled each stage he rode upon, with eclectic gesturing and long, flowing locks of a greased coif. One journal called him America’s most handsome man. He needed to be fawned over, and his early success only made him more desperate for attention.

When the war broke out, he went wherever he had the most loyal fanbase, eager for an audience’s cheers. His private distrust of Lincoln’s motives in defying the secession of Southern states primed Booth for a meteoric rise in said states. Those private misgivings became his public cry. Booth was by sympathy, and in no other way at all, a Confederate. . His acting was impressive by all accounts. He enjoyed Macbeth and Julius Caesar, particularly requesting the part of Brutus, who he increasingly saw as a folk hero against the tyrannical Caesar.

If he was Brutus, then Abraham Lincoln was his Caesar. After a failed attempt to kidnap the president and hold him for ransom, the war ended in favor of the Union. Booth despaired. Booth went solo, then, in a rage to Ford’s Theatre where he knew Lincoln would be a few nights after Appomattox. He’d performed on that stage. Lincoln sat suddenly with a bullet in his head. Haphazardly the assassin Booth jumped from the balcony, shattering one of his legs before hobbling off into a short-lived hiding. He was killed a dozen or so days later in a burning barn, unwilling to surrender. Booth’s finale was having a bullet lodged in the back of his own head. It was the kind of ending ancient Greeks might appreciate.

While these events took place, George Washington Smothers settled down in Mountain Home, Arkansas with his Louisiana wife. She (Phobe) is my ancestor rather than Zanie, of whom no memory has been preserved by my living kin.

George Washington Smothers somehow fought through America’s bloodiest war without so much as a scratch, but life has a way of catching up with a man like him. He’d had thirteen children with Phobe by this time, and he was tilling a field to provide for them. But the harvest didn’t come in one year. And, the story goes, he owed some people some money. For what, I’ll probably never know, but it was enough to drive him to the edge.

His end came by his own hand in the middle of his field one day. Lady Fortune’s wheel had spun and would spin again, for none of his children succumbed to starvation in the coming years. Each one survived, and only a few generations later, the story of the Booths and the Smotherses crossed.

My grandmother, Betty Jean Smothers (Nanny), was a descendant of the Booth family. Left down and out after their name was poisoned by the assassin, moving around seemed the only way to go. Some of them stuck in Missouri, oddly enough, but my branch settled in Columbia County, Arkansas. Nanny’s mother, Onaree Short, or Maw Lucy as my dad knew her, lived there and married a man called Calvin who served in the Pacific Theatre in the Second World War. After his back and hip caught shrapnel from a hand grenade, Calvin came home, and the family settled in Onaree’s hometown of Waldo, Arkansas. Nanny grew up there and fell in love with the handsomest, goofiest troublemaker in town: Billy Smothers, the grandson of George Washington and Phobe.

I’d be here whether I knew these stories or not, sure. Plenty of people walk around having no idea they come from fugitives or bigamists. But this is a rich inheritance no one can give or take away. Knowing your family’s past fugitives and pretty boys is the kind of localism anyone can aspire toward and practice.

Before moving from our proverbial Manhattans to our personal Port Royal’s, before disavowing your computer or cell phone in the name of localism, recall and recite your stories. It’s an attainable step for those of us who can’t buy homes yet, or those in our ranks who don’t know a zucchini from a cucumber.

In writing on John Wilkes Booth’s personal character and early life. I owe everything to “The Boys’ Life of Abraham Lincoln” by Helen Nicolay and George Alfred Townsend’s “The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth”. I owe some of my word choice to other folks, too, most notably James Matthew Wilson’s poem “Return to St. Thomas,” and Jim Webb’s “Born Fighting.” For the family aspect of this tale, I owe thanks to my Uncle Jimmy, my father, and several good folks who are now dead, most especially Nanny.

Image via Picryl