As a child, growing up in the Netherlands, I loved making jigsaw puzzles. I was a rather quiet and sensitive girl with an extraordinary sense of focus. I sat for hours just reading the children’s encyclopedia my parents had given me. At times, I would go out to make ‘soup’ in the garden, practice the violin, or make a jigsaw puzzle. When I entered the murky waters of puberty, I quickly learned that most of the activities that had filled my childhood with joy were not held in high regard by my teenage peers. As such, I traded my books for TV series, my violin for popular music, and my jigsaw puzzles for endless socializing. Like most of us, when I entered the deep waters of adulthood, I happily found my way back to many of my childhood pleasures. I joined a community orchestra to play the violin, became a regular at my local library, and still love to make soup, albeit with slightly more edible ingredients. But jigsaw puzzles were one of those childhood pleasures that never quite left the shallow end of the pool of my life.

That is, until I moved to Los Angeles. Of all the possible reasons to move to California, I went to study Islamic law. The irony was never lost to me. To make the divine joke even funnier, in Los Angeles, I was to pursue doctoral research on Islamic law and ecology. In the heart of the entertainment industry, inequality, and limitlessness, I was to write about environmental justice. I was to write about the soil in a city of concrete. What a master plan for hypocrisy.

But somehow, mercy was also a part of the plan. As usual, she showed up where she was least expected. In graduate student housing, I was paired with a housemate who was equally worried about the threat of moral corruption and hypocrisy. So, together, we light-heartedly and imperfectly committed to nonconformity. My housemate taught me how to turn a room into a home from scratch, using only gifts, hand-me-downs, and thrift-store finds. On my bike, I cruised along the eight-lane road from our apartment to the supermarket. And on Saturday nights, we sipped the tea we bought at our only neighborhood shop: the liquor store.

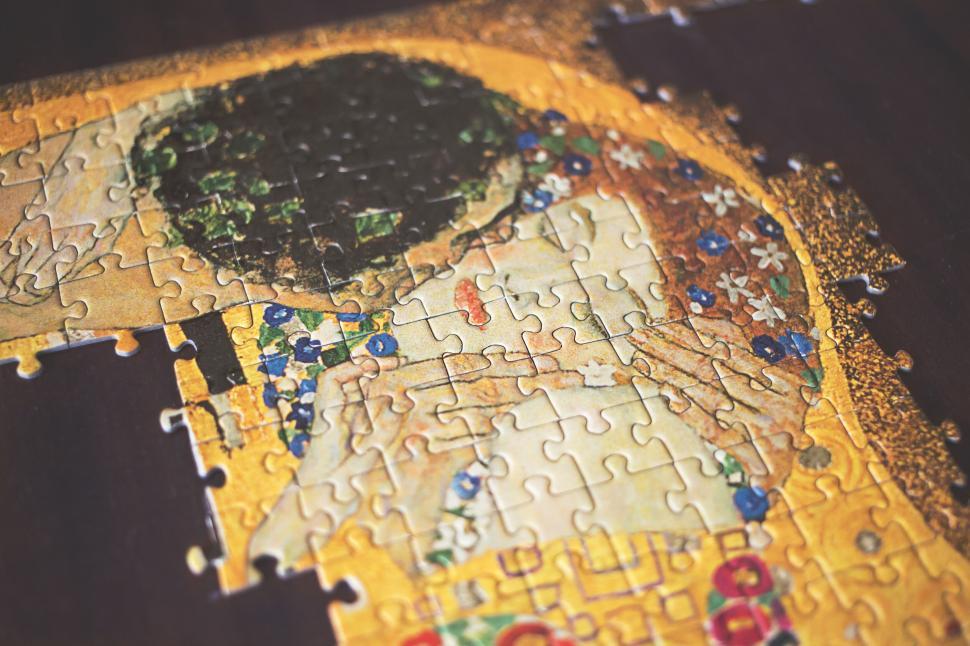

When my birthday came around, my housemate bought me a gift: a jigsaw puzzle. I cannot describe the childlike joy I felt opening the box. We didn’t have a table big enough to make the puzzle, so instead, we made our own from a large panel we found in our building’s garage. In the absence of a television, this newly built puzzle table became the centerpiece of our home. I lost count of the amount of puzzles we solved whilst sipping tea. Our days progressed with the rhythmic intermission of regular ‘puzzle breaks’ as we connected in the heart of our home, in silence, or in honest conversation, sharing whatever was on our hearts and minds.

There is a deep beauty and comfort in helping puzzle pieces find the place where they belong; in watching clarity arise from confusion, and harmony from chaos. As we worked through the puzzle, we also worked through the puzzles of our own lives. We worked through confusion, grief, delusion, depression, and fear. At times, our pieces found their proper place. At times, we got to see the bigger picture of our lives more clearly.

In my mother tongue, ‘to puzzle’ is a verb. In our Angeleno household, we created space within the English language for me to feel at home. And so, we ‘puzzled’. At times, whilst puzzling, we experienced a looming sense of guilt. After all, there were so many books left to read, and papers left to write. There were emails to be answered, calls to be returned, events to be attended, and problems to be solved. But amidst the limitless demands and stellar expectations, we found our peace, piece by piece.

Throughout history, puzzles have been one of those rare commodities the demand for which grows in times of economic downfall. Jigsaw puzzles first became majorly popular during the Great Depression, when unemployment rates skyrocketed, and commercial entertainment became inaccessible for many. Jigsaw puzzles were satisfying and inexpensive, brought families and friends together in their homes, and gave the puzzlers and producers a sense of fulfillment. Many skilled workers who had lost their jobs made jigsaw puzzles in their attics and garages in an attempt to provide for their families. Puzzle libraries and rentals popped up all throughout the United States and thrived. But, as the economy ‘recovered’ and the beast of capitalism regained its appetite, puzzles were forgotten, left to be enjoyed only by the little ones who were not yet taught they needed more.

I am often greeted with laughter when I, a grown woman, declare my love for jigsaw puzzles. They are childish, useless, and boring, I am told. I have to admit, that’s why I love them. Part of the joy I get from puzzling is directly born from the misconceptions of others.

Puzzling is not boring and useless like doomscrolling, or childish like gossip. Rather, puzzling is boring and useless like meditation, and childish like religion—in the very best sense of those words. It is ‘boring’ because it provides a healthy antidote and alternative to the overstimulating and often screen-based entertainment we have become used to. It is ‘useless’ because it does not produce anything profitable or new. And it is ‘childish’ because it is not worth boasting about—because it is innocent and simple.

Like religion, puzzles are childish in the sense that they address an essential aspect of human nature: our search for meaning, connection, and understanding. In the world of a jigsaw puzzle, we can bathe in the certainty that every single piece has a purpose; every single piece belongs somewhere in the bigger picture. In the world of a jigsaw puzzle, we know it is only patient effort that separates the promise of harmony from the presence of dissonance.

So many in our secularized world no longer see their lives as a jigsaw puzzle. But children do. Children ask questions to try and make sense of the puzzle, fully believing that there is a ‘sense’ to be found. In the Islamic tradition, the term fitra is used to describe the innate human nature that is aligned with the natural order of creation. In Surah Ar-Rum, ‘The Romans,’, the thirtieth chapter of the Qur’an, humanity is instructed, “direct your face toward the religion of truth – the natural order (fitra) of God by which He has created all of humankind.” (Qur’an 30:30).

In line with the Biblical narrative, the Qur’an presents this world as the creation of a divine Creator, as the intentional speech of God. The Arabic word used to describe verses in the Qur’an, ayah, is the same word that is used by the Qur’an to describe God’s signs in creation. The Qur’an instructs its audience to read the divine speech of creation and reflect upon it night and day, whilst sitting and standing, in rest and in work (Qur’an 3:191).

The joy we find in solving puzzles is a part of this same human nature. It is a part of the innate human desire to find meaning, connection, and understanding. But the best part is, nobody ever needs to know that it is a spiritual affair, and as such, it is uniquely protected against hypocrisy, like the sheltering labyrinths of ancient monasteries. Similar contemplative practices, like meditation or even prayer, are commonly dressed in the cloak of piety. Often, this piety is sincere. But hypocrisy, too, easily finds comfort in piety’s embrace. In contrast, the cloak of childishness is not so tempting a garment for her. Those who wear that blessed cloak, play their way into the Kingdom of God without any spectators or entrance fees. Like prayer beads, the puzzle pieces glide through their hands, as they smile a secret joy.

When I visited Wendell Berry to sit with him, we discussed our perspectives on environmental justice as informed by his Christian and my Islamic worldview. Together with a dear Muslim friend of mine, and with Wendell’s wife, Tanya, we sat around their kitchen table. There, at that big table, with a cup of tea, we puzzled. “What is justice?” Wendell asked me, with sparkling eyes. For three hours, we puzzled with that question, trying to create a clear picture. Three hours was not nearly enough time to complete it. We completed a framework, the edges, of balance between rights and obligations, but somehow, it seemed the puzzle only got more confusing the longer we worked on it. We puzzled some stories and anecdotes together, as well as some dark patches of pain and loss. Overwhelmed by the chaotic picture we were faced with, I asked Wendell, “Have you ever thought of giving up?” He smiled. “No,” he said, “because I have already lost.”

The way of the puzzler is not about reaching a certain goal. If it were, the perfectly fine image would never have been broken up to begin with. The way of the puzzler is about the puzzling itself. Engaging in the puzzle of this life, with all its complex challenges and confusion, is not about eliminating all chaos. Rather, it is about a continuous commitment to strive for harmony and order, as well as the community, goodness, and purpose found in that pursuit. It is about cultivating an unshaken belief in a bigger picture in which all pieces unmistakenly belong, even if that picture is beyond our vision. It is not about completing the endless puzzle of chaos, or winning the endless struggle against evil—it is about the ‘boring, useless, and childish’ puzzling itself.

And so, amidst uncertainty, terror, injustice, and corruption, I slowly watch the pieces fall into place. Piece by piece, a picture of peace arises in the heart of the chaos itself. Clearly, puzzling is not going to save the world. It is not even meant to. But somehow, it has a revolutionary power. It’s a quiet revolution, and a small one, but in our world of noisy greatness, there is great power in a silent smile.

Image via Freerange Stock