Rudyard Kipling’s 1902 Just So Stories are a delightful anomaly—they feel like folk tales but were largely invented by Kipling himself as bedtime stories for his eldest daughter, Josephine. Thus, unlike the fairy and folk tales that come down to us from compilers like the Grimm brothers, the Just So Stories are a product of a single mind and have a cohesion to them not found in the broader folk-tale literature.

He was once one of the most popular modern authors, but Kipling’s reputation has been damaged, probably forever, by his cultural association with the British Empire and the “white man’s burden” that drove it. This is not an entirely fair association. Kipling’s work certainly emerges from those historical conditions and, to be fair, is unthinkable without them—but at its best it does emerge and stands on its own two feet. The Just So Stories in particular are worth reading for their whimsy and imagination. Colonialism, it’s true, occasionally rears its head in them, but it’s a relatively minor theme in the stories, especially when compared to Kipling’s works for adults, like Kim.

The phrase “just so story” has made its way into the popular lexicon even as Kipling’s own examples of the genre may be in danger of disappearing from the popular imagination. Most often I hear the term applied to a certain sort of evolutionary-psychological explanation for human behavior or culture: a tidy explanation presented without evidence, an explanation that amounts to a kind of materialist mythology. Kipling does something similar in these stories—without, of course, meaning for them to be taken seriously as explanations for human and animal behavior.

One thing that sets Kipling’s versions apart from scientific “just so stories” is the role that he has human beings playing in animal evolution. Perhaps this should come as no surprise. While Kipling himself subscribed to no particular religion, he grew up in Christendom and was no doubt familiar with YHWH’s charge to Adam and Eve: “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen. 2:28, NRSV). What we see in many of the Just So Stories is Kipling’s fanciful description of what that dominion looks like.

Nowhere is the dynamic clearer than in the collection’s opening story, “How the Whale Got His Throat,” an attempt to explain why an animal as large as a whale would eat only tiny animals like krill. As it turns out, he didn’t always: the whale once had such an enormous appetite that he ate all the fish in the sea save one, who directed him toward a mariner shipwrecked in the North Atlantic. The whale has power and size, but the sailor “is a man of infinite-resource-and sagacity” (4)—the very evolutionary advantages that have allowed human beings whatever triumphs we’ve achieved over the natural world. The whale swallows the man, who, in the dark “cupboards” of his guts, thrashes about and makes himself enough of a nuisance that the whale eventually agrees to swim to Britain and drop him off there.

The story thus far has certain similarities to the biblical story of Jonah, who also famously ends up inside a whale for three days. But Jonah’s escape has nothing to do with his own resources and sagacity; instead, the would-be prophet is helpless in the belly of the whale until he prays to God, who “spoke to the fish, and it spewed Jonah out upon the dry land” (Jonah 2:10, NRSV). Here’s a difference between Kipling’s anthropology and the Bible’s: the men and women in his stories have their dominion over the world not by divine fiat (at least not by divine fiat alone) but by their own power and intelligence.

As it happens, Kipling’s mariner is not content merely to have the whale deliver him back to his homeland. When he exits the whale’s mouth, the whale discovers that he has “taken his jack-knife and cut up the raft into a little square grating all running criss-cross, and he had tied it firm with his suspenders [ . . . ], and he dragged that grating good and tight into the whale’s throat, and there it stuck!” (6). The whale’s strange diet will thus be forever and always a reminder of humanity’s ingenuity and superiority.

“How the Rhinoceros got His Skin” is structurally similar. Its human hero is a Parsi who owns a stove that only he is allowed to use. (Note the parallel to Genesis: in the Garden of Eden, God makes a tree off-limits to humanity; here, it’s humanity making their technology off-limits to everyone else.) The rhinoceros, still smooth-skinned in those days, steals a cake from the Parsi, who waits to get his revenge. When a heatwave strikes the area, the rhinoceros takes off his skin to bathe in the ocean, at which point the Parsi sneaks up and fills it with stale cake crumbs. Then he climbs a palm tree and hides, waiting to watch the rhinoceros realize that he’s been had. To the rhino’s horror, nothing he rubs up against can do anything about the unpleasant feeling of the crumbs in his skin: “So he went home, very angry indeed and horribly scratchy; and from that day to this every rhinoceros has great folds in his skin and a very bad temper” (30). When nature comes into conflict with humanity, Kipling says, humanity wins through its trickster cunning.

Other stories suggest a less contentious relationship. The collection’s most famous piece is probably “How the Leopard Got His Spots.” Here the transformation happens to both man and beast. The leopard is friends with an Ethiopian, and the two of them “hunt together—the Ethiopian with his bows and arrows, and the Leopard ‘sclusively with his teeth and claws” (38). The prey animals—a giraffe and a zebra—get tired of it, and the two of them move from the veldt to the jungle, where exposure to dappled sunlight gives them the spotted and striped coats we know and love.

Sure enough, they are disguised, and a wise baboon advises the Ethiopian and the leopard to “match [their] backgrounds” (45) if they want to have any luck hunting. The Ethopian—himself wiser than the leopard—quickly takes this advice and changes his skin color “to a nice working blackish-brownish color, with a little purple in it, and touches of slaty-blue” (45)—just the thing to hide from his prey. But the leopard has to be convinced, and eventually the Ethiopian has to threaten not to hunt with him anymore. When the time comes for the leopard’s transformation, it is the Ethiopian who enacts it, by rubbing some of the black off his own skin and pressing his fingers all over the leopard’s fur. It’s not a competitive relationship; the Ethiopian is friends with the leopard and is more than happy to help him out. But neither is it a relationship of equals: the leopard is capable of change only because the human being changes first and thoughtfully offers to help him.

In two stories, supernatural beings are the direct agents of change, but humanity is the catalyst. In “The Crab That Played with the Sea,” “the Eldest Magician” sets the world in order by telling all the animals to “play at being” what they are (141). The man resists:

[H]e said, ‘What is this play, Eldest Magician?’ And the Eldest Magician said, ‘Ho, Son of Adam, this is the play of the Very Beginning; but you are too wise for this play.’ And the Man saluted and said, ‘Yes, I am too wise for this play; but see that you make all the Animals obedient to me.’ (142)

This exchange parallels the Genesis account, with an important distinction: there, man’s dominion over the natural world is a gift from God, but here, he demands it, and God gives it to him.

But his dominion is imperfect: the sea doesn’t obey him. Every day it drives back up the river and floods his house, and every night it withdraws so far back away from the land that there’s nothing left in the river but mud. As it turns out, it’s happening because Pau Amma, the crab, got impatient when the Eldest Magician was handing out roles and went off into the sea on his own. (In a charming detail, it’s the story’s version of Kipling’s daughter who figures this out.)

Pau Amma has an outsized sense of his importance. As the narrator wryly points out, “though he was a King Crab, he was nothing more than a Crab, and the Eldest magician laughed” (150). Pau Amma has been ignorant or dismissive of what Arthur O. Lovejoy called the “great chain of being”; he even goes so far as to blame his failure on the man: “If he had not taken up your attention,” Pau Amma tells the Eldest Magician, “I should not have grown tired of waiting and run away, and all this would never have happened” (152). Either way, the Eldest Magician’s hands are tied, because the divine order has already been bestowed on the world.

Thus it’s humanity’s turn to bestow order. The man makes it so that Pau Amma can live in both the land and the sea, and his daughter gives the crab a pair of scissors to defend himself and to crack coconuts open. To these blessings the Eldest Magician adds a curse: he makes it so that once a year, Pau Amma’s shell becomes soft, “to remind you and all your children that I can make Magics, and to keep you humble” (152-153). God has ceded control of the world to humanity, his highest creation, even if he maintains some rights himself. He also maintains one curse for the man: “You are lazy [ . . . ] So your children shall be lazy. They shall be the laziest people in the world. They shall be called the Malazy—the lazy people” (156). But even here, man has the final word, negotiating to have the sea work for him by ebbing and flowing every day.

The Eldest Magician doesn’t appear in “How the Camel Got His Hump,” but it still involves a violation of human dominion and a corresponding punishment. The story takes place “In the beginning of years, when the world was so new-and-all, and the Animals were just beginning to work for man” (13). The Camel refuses to work, however, and sits alone in the desert to avoid his responsibilities. The other animals report his laziness to the man, who apologizes for not being able to do anything about it. This time it’s “the Djinn in charge of All Deserts” (16) who delivers the punishment, giving the camel the hump that allows him to work without eating for three days at a stretch. Man, in this case, is not powerful enough to change an animal—but the change takes place once again for man’s benefit.

But the strangest and best of the Just So Stories is “The Cat That Walked by Himself,” a story about the domestication of animals and the places where that domestication is, shall we say, imperfect. The story begins when all the now-tame animals were still wild—including the man: “He was dreadfully wild. He didn’t even begin to be tame till he met the Woman, and she told him that she did not like living in his wild ways” (161). Thus the woman is the agent of domestication, which, like charity, begins at home: “She picked out a nice dry Cave, instead of a heap of wet leaves, to lie down in; and she strewed clean sand on the floor; and she lit a nice fire of wood at the back of the Cave; and she hung a dried wild-horse skin, tail-down, across the opening of the Cave” (161, 164). This cheerful cave will be the gateway through which animals step when they choose to submit themselves to humanity.

The wild animals are suspicious at first, but one by one, they begin to see the advantages of coming inside the cave. The woman offers to let the dog eat as many roast bones as he likes if he’ll help her husband hunt and guard the cave at night; when he agrees, he stops being their enemy and becomes their “First Friend” (166). The horse is a little more suspicious, but when he sees the woman’s supply of hay, he agrees to carry the man and the woman wherever they want to go in exchange for it, earning him the name “First Servant” (168). And the cow agrees to exchange her milk for that same hay. Bit by bit, the woman builds a farm around the cave.

The cat holds out, though. “This is a very wise Woman,” he says, “but she is not so wise as I am” (166). He would like to maintain his autonomy from the human beings, whom he continues to call enemies: “I am not a friend, and I am not a servant. I am the Cat who walks by himself” (169). Nevertheless, the cave appeals to him, and he would like to come in, sit by the fire, and drink milk. The woman makes a deal with him: if she compliments him once, he can come into the cave; if she does it twice (which she does not expect to do), he can come sit by the fire; and if she does it three times (which she really does not expect to do), he can drink his fill of the cow’s milk. In this way, she tricks him into wanting to be domesticated.

He gets his opportunity when the man and the woman have a baby. A bat who lives in the cave with them tells him that the baby is “fond of things that are soft and tickle. [ . . . ] He is fond of warm things to hold in his arms when he goes to sleep. He is fond of being played with” (171). One morning the woman is busy cooking when the baby starts crying; unable to get him to stop, she sits him outside the cave with some pebbles to play with, but it’s no use. The cat has more luck. Patting the baby with his paws and tail, he gets him to stop crying, and the woman, not knowing what animal has accomplished this feat, says that it’s a blessing to her. That’s compliment number one, and the cat can come inside the cave.

But the woman is angry—or pretends to be angry as part of the long con—and when the cat goes away, the baby cries again. The cat has the woman make him a play toy, a spindle with a long piece of yarn attached to it, and when the cat bats it across the floor in that distinctive feline way, the baby laughs and stops crying. The woman tells the cat he’s acted very cleverly. That’s compliment number two, and the cat can sit by the fire.

The woman gets so angry—or again, pretends to be angry as part of the long con—that the cave becomes very still. A mouse believes that no one is home and scampers across the floor. Our cavewoman is very wise and very resourceful, but she’s afraid of the mouse, jumping up onto a chair. The cat asks her if eating the mouse would be a favor to her, and she asks him to do it as quickly as he can. “A hundred thanks,” she tells him. Even the First Friend is not quick enough to catch little mice as you have done. You must be very wise” (176). That’s compliment number three, and now the cat is allowed to drink milk three times a day.

Nevertheless, the cat insists that he has not been domesticated: “But still I am the cat who walks by himself, and all places are alike to me” (177). This time she doesn’t get angry at him: she laughs, because she knows that the cat is lying to himself about what his relationship will be with humanity. When they return from hunting, the man and the dog are less pleased; the man promises to throw things at the cat, and the dog promises to chase him up a tree. And so, it seems, have all men and dogs done down to the present day.

What’s happened here? The cat has, to some extent, gotten one over on the woman, wise though she may be. He has his run of the cave, but he’s not bound to it—he stays there with the people when he feels like it, and the rest of the time he roams the world. And yet it’s simply not true that every place is alike to him: if it were, he would not return to this particular place every day. So the woman has, to some extent, gotten one over on the cat. She has partially domesticated him, although I think the better way to say it is that the two of them have domesticated each other. In this story—the last in the collection that actually claims to explain some aspect of animal behavior or biology—we find out that human dominion is vast and powerful, but that there is at least one animal that challenges that dominion and puts some limits on it. No one who has ever told a cat to do something would disagree.

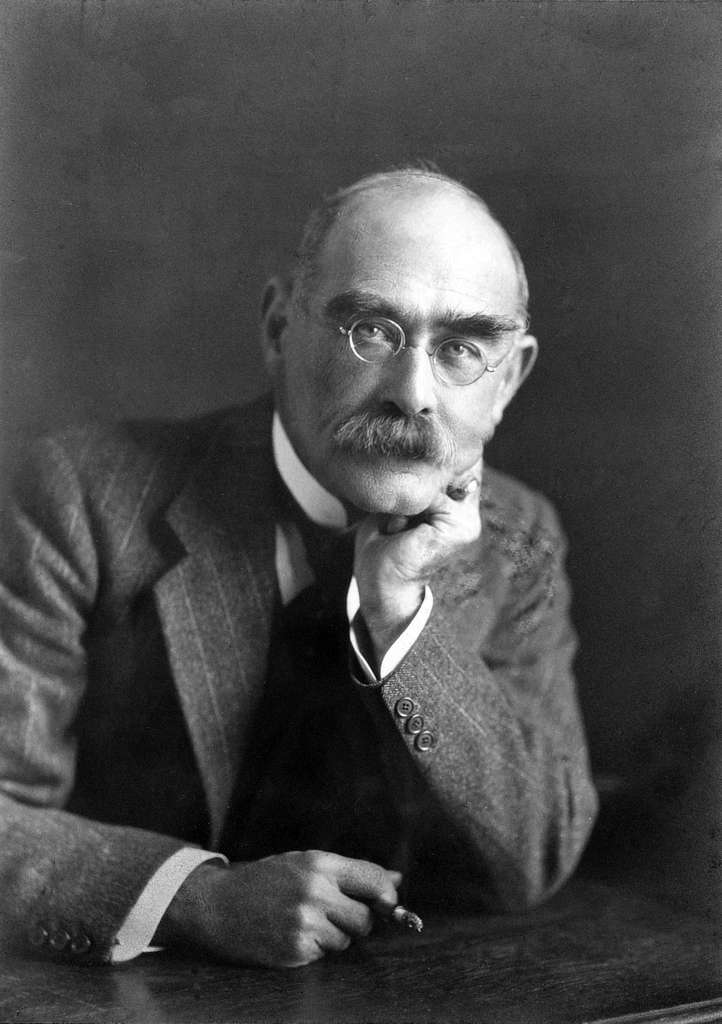

Image via Picryl