Over the last several years, various outlets have hosted conversations about something called “conservative art,” why it is less successful than “progressive art,” whether conservatives simply have bad taste, or or whether merely by being such backwards folks they are incapable of producing decent art, and so on.

For instance, at The Imaginative Conservative James Baresel worries about “The Dilemma of the Conservative Artist”. He asks what conservatives can do “to facilitate the work of conservative artists.” But, what, exactly, is a “conservative artist”?

A search for “progressive art” on Google yields well over a million hits, while “conservative art” only yields a quarter of a million. Is this an indication that progressives are much more likely to produce good or great art than are conservatives?

In a recent piece titled “TV Is Always Progressive”, Mary Harrington suggests that part of the answer to the question of why art “leans left” is that “conservatives have terrible taste.” (She goes on to argue that for TV and movies “the media they rely on to propagate is progressive by definition.” he may be completely correct on that point, but that is orthogonal to the topic of this essay.) Along the way she offers a definition of art: “a fusion of moral, aesthetic and political impulses…”

Now, in general, I am a great admirer of Harrington’s work, but here I think she has missed the mark in her understanding of what art is. I do not deny that often a miscellany of activities is going on nearly simultaneously in some person’s life. One may be making love to one’s spouse, while also watching a golf tournament on TV, and planning that evening’s dinner. But that does not mean that making love consists of a “fusion” of those various activities. (And what would such a “fusion” even be?) Similarly, someone may be painting, while alternately attending to the beauty of their painting, whether the painting will advance the worldwide socialist revolution, and if it will help the painter seduce the lover he has been pining for. But that no more makes such a miscellany the differentia of art than does the previous miscellany represent the differentia of sexual intercourse. What, then, does differentiate art from other human activities?

In his essay “The Voice of Poetry in the Conversation of Mankind,” Michael Oakeshott says of “poetry,” by which he means artistic activity in general, that its essential character is to take contemplative delight in the conceptual image that a work of art presents. He writes that “images in contemplation are merely present… [they are] neither pleasurable [inciting desire] nor painful [inciting aversion]; and [they do] not attract… either moral approval or disapproval.”

This understanding of art is not a novelty of Oakeshott’s: it is to be found much earlier, in fact, at least as far back as Aquinas. For a brief synopsis of the Aquinas’s understanding of art, let us turn to James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man:

“You see I use the word arrest. I mean that the tragic emotion is static. Or rather the dramatic emotion is. The feelings excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to possess, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion (I used the general term) is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing.”

It might be helpful to clarify what Aquinas (via Joyce) means. “Proper” art does not mean art that respects boundaries of propriety, but art achieving a properly artistic end: that of “arrested” contemplation on the artistic image itself. It is “proper” in the same sense as driving a nail into wood is the proper use of a hammer. Pornographic art, in contrast, moves us emotionally to desire or loathe its image: when we call TV programs showing fabulous homes “real estate porn” we are implicit Thomists. Didactic art also achieves the same effect, but by attempting to intellectually, rather than emotionally, convince us that we should desire or loathe its subject. Aesop’s Fables come to mind here.

But why can’t someone do both at once? Why can’t one try to make the case for, e.g., some political cause, while also producing an excellent work of art? Well, because no man may serve two masters. Imagine you are the manager of an NBA basketball team; you set the team the simultaneous goals of:

- Winning the NBA championship

- Hiring as many disabled players as possible.

It should be clear that to the extent you focus on one of these goals, you are less likely to succeed at the other. And so it is with someone creating a novel, or a play, or a painting: to the extent their focus is on making a case for some political cause, it is not on making great art.

Conservative art is bad not because conservatives have “terrible taste” (as Harrington would have it), or lack imagination, but because the very term shows it to be a mongrel beast of low breeding: art is its own species, as is politics, but “conservative art” tries to force them to produce fertile offspring. “Progressive art” of course has the exact same problem: it merely has the advantage over conservative art of being fashionable.

To the extent that progressive art is actually “better” than conservative art, I think it is largely the effect of ambition: for a budding artist with talent, it will be obvious that mixing progressivism with their art will advance them in their profession, while even a whiff of conservatism could end their career. Kay Clarity, in her essay “The Plight of the Conservative Artist in a Liberal World”, makes this point:

“The conservative artist is either explicitly starved out of her industry, or she is forced to work on projects antithetical to her convictions, stifling her authentic perception and raison d’etre as artist. Taking also into account the influence of the near-universal peer ideology, few survive in this climate with their convictions and artistry intact.”

Clarity goes on to note that answering this bias with an attempt to promote “conservative art” backfires:

“There are limited niche conservative projects, but while these don’t violate the conservative element of the artist’s convictions, they do, unfortunately, often violate his artistic ones – an unfortunate ‘other side’ to the unique challenges of the conservative artist. Propaganda remains propaganda even if it is essentially true; it is a controversial, oversimplified means of communication, and one that is certainly outside of the voice of any valuable artist.”

Baresel, in the piece linked to above, makes much the same point (although I would be reluctant to say that someone writing a “novel” or directing a “movie” with the primary aim of pitching a conservative political platform is acting as a “philosopher”) when he writes:

“One factor in why conservatives are alleged to produce bad art is the fact that certain efforts at ‘conservative art’ in fiction and film are, in fact, the work of ‘philosophers’ rather than of ‘artists.’ In these cases, the outward form of a novel or of a movie is used as a mere vehicle for the expression of conservative ideas. The ideas may be entirely correct but the artistic failure will not give aesthetic pleasure and will not convince anyone of the ideas expressed aside from those who already accept their truth. A good novel can only be written by someone who is primarily concerned with the beauty of his work rather than with the ideas which it contains.”

The great novelist Milan Kundera went so far as to coin a new word for those who would force art to serve political ends:

“To be without a feeling for art is no disaster. A person can live in peace without reading Proust or listening to Schubert. But the misomusist does not live in peace. He feels humiliated by the existence of something that is beyond him, and he hates it. There is a popular misomusy… But there is an intellectual, sophisticated misomusy as well: it takes revenge on art by forcing it to a purpose beyond the aesthetic. The doctrine of engagé art: art as an instrument of politics.”

There is nothing preventing someone of conservative political inclinations from producing great art, except the misapprehension that their art must somehow support conservative politics. And so may someone of progressive political inclination produce great art. Nevertheless, conservatives may actually have an advantage here, in that at least some varieties of conservatives are less committed to the idea that everything must have political implications than are most progressives.

None of this is to say that even the greatest artists do not mingle non-aesthetic concerns into their art, nor am I trying to set up some rule that they should never do so. In fact, perhaps a certain sprinkling of non-aesthetic bits throughout a work of art serve to enhance its aesthetic character, in the same way that a few bits of anchovies may make an otherwise delicious salad more interesting.

Nevertheless, if someone of a conservative disposition wishes to produce excellent art that, in a certain sense, supports conservatism, the best thing they can do is to focus simply on producing excellent art. They should no more try to produce “conservative art” than a conservative plumber should try to produce “conservative plumbing,” or a conservative ornithologist should try to produce “conservative ornithology.” Along the way, the “conservative artist” might just illustrate the point that conservatives are not entirely obsessed with politics, as so many progressives are.

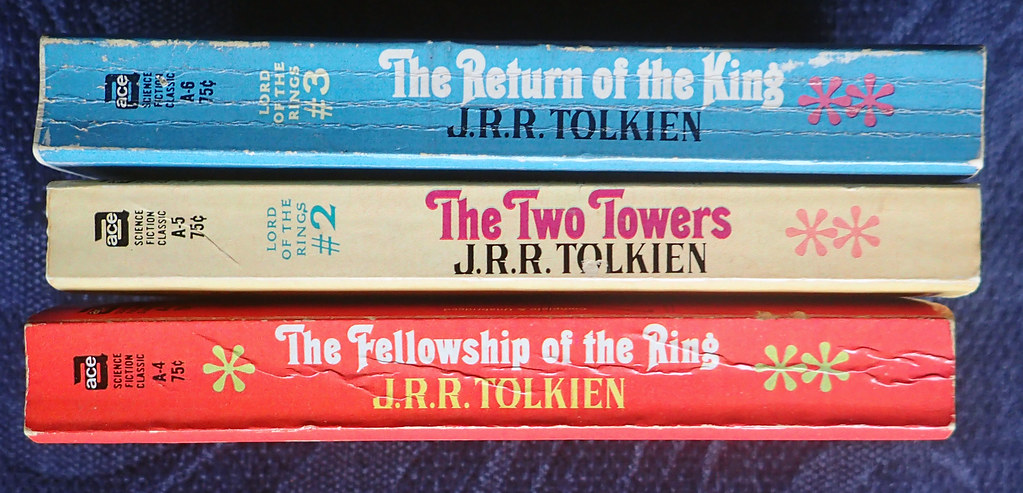

Image via Flickr

While it might be that art should not be ideological, to the extent that art reflects reality there may seem to be some “ideological” content to it. And that is due to reality either being something or not. It comes down to a worldview difference. If an artist seeks to capture something beautiful about reality with an Author, it will be different compared with the work of an artist who either sees reality as random and subject to our inner-ness.

The idea that it comes down to what is popular makes sense. Reflecting the Author is out of vogue.

Eugene, thanks for this excellent essay. Robert, a quibble with your comment. It is more accurate to say an artist is attempting to make something beautiful in the act of contemplating and rendering reality. It is the made work itself that is beautiful, not the real object or subject of the artist’s imagination, experience, or memory. This is why didactic works always fall short of being beautiful, even and especially when the didactic maker chooses an object of beauty to render. This is why we can take pleasure in the experience of art by progressive artists, if the artist approaches their art in this way, he or she is more likely to produce something of true beauty. As a literary artist, I often enjoy novels and short stories written by writers who would never be categorized as “conservative.”

Comments are closed.