I lived in the same house from age three to eighteen, when I left for college. Not counting the two or three dorm rooms I lived in as a freshman and sophomore, I’ve lived in eleven houses or apartments in the intervening 24 years. Some of these moves were necessitated by professional changes; the academic’s peripatetic life is well known. But at least a few of them were motivated by a vague dissatisfaction, a sense that I’d be happier living, say, in a high-rise in downtown Omaha than in an apartment in the suburb of Ralston.

I don’t need to tell anyone who has ever moved that it’s a horrible and inhuman process. Our nomadic ancestors, perhaps, had an easier lot of it because their lives were designed to be mobile. But our society seems to have worked out the worst possible combination: we think of ourselves as settled, and we accumulate property as if we were, but many of us move, as I have, every two or three years. (My longest adult habitation was an apartment in Minnetonka, Minnesota, where I lived from 2014 to 2019.) Thus, every time we move we’re forced to pack it all up.

Most recently, my wife and I have moved from a townhouse in a suburb of Atlanta to a single-family house in another suburb of Atlanta. The move was particularly unpleasant, partly because we owned that townhouse and had to go through the process of staging and selling it; partly because of the gap between when we had to move out of the townhouse and when we could move into the new house; and partly because we have accumulated even more stuff.

Part of the reason we wanted to move is so we could have a dedicated library, which will take up about half of the finished basement at our new house. I left higher education in 2019, and when I did, my wife and I sold off about a third of our massive collection of books. It’s the only time in my life I’ve ever gotten rid of a sizable number of books, and I wish I hadn’t done it. I suppose it was a gesture toward the new life I imagined I’d be starting; we didn’t need all those books, I told myself, not realizing that my identity as a book collector had already been formed and that there was no changing it at age 37.

A “collector,” I’ve called myself. I’ve always hated the term because it brings to mind someone who accumulates objects for a sort of totemic value: the arrested adolescent who keeps his Star Wars figurines in their original packaging for fear that their value will depreciate. That’s not me–I don’t care about first editions or luxury reprints, and I don’t want uniform shelves of leather-bound hardcover books. I’m perfectly happy with cheap paperbacks, and I obsessively annotate even low-brow books. My library, in other words, is practical.

And yet I have certainly not read every book on my shelves, not even after the Great Culling of 2019, and I’m never going to. I can say, with the narrator of Saul Bellow’s Dangling Man (which, unlike several other Bellow books in my collection, I have read), “I was forever buying new books, faster, admittedly, than I could read them. But as long as they surrounded me they stood as guarantors of an extended life, far more precious and necessary than the one I was forced to lead daily. If it was impossible to sustain this superior life at all times, I could at least keep its signs within reach.” That sounds pretty totemic to me, and certainly not practical in any meaningful sense.

When we moved into our townhouse in 2020, we designed a spare bedroom as our library. (Eventually my wife would work from home, and it became her office, an arrangement that pleased neither of us.) I spent an obscene amount of money on four very nice seven-foot bookcases: three of them were six feet wide, and the fourth (the “small” one) was four feet. They were so heavy that I think I gave myself a hernia trying to carry them up the stairs in their boxes, and it took two weeks to put them together, but damn if they don’t look great: dark wood, not particle board, and heavy-duty enough that the shelves don’t bow under the weight of my abundant books.

One of my many anxieties about moving out of the townhouse was that the movers would not be able to get these assembled bookcases around the tight turn from the upstairs hallway into the stairwell and that we’d have to take them apart. This anxiety was well-founded; the movers managed to get the small bookcase out the front door, but we spent about two hours taking the others apart. All the hardware for these bookcases went into two sandwich bags.

As you might imagine, I promptly lost one of the sandwich bags, which means that my library is only half-constructed, pieces of the bookcases scattered across the basement floor. It’s a nerve-wracking experience, albeit a minor one in the grand scheme of things. If Bellow’s protagonist is right about the experience of being surrounded by books (and I think he is), the transcendent world that my books point to is only half-indicated; I’m hung between two worlds, unable to quite make it to the next one. (I’ve ordered new parts.)

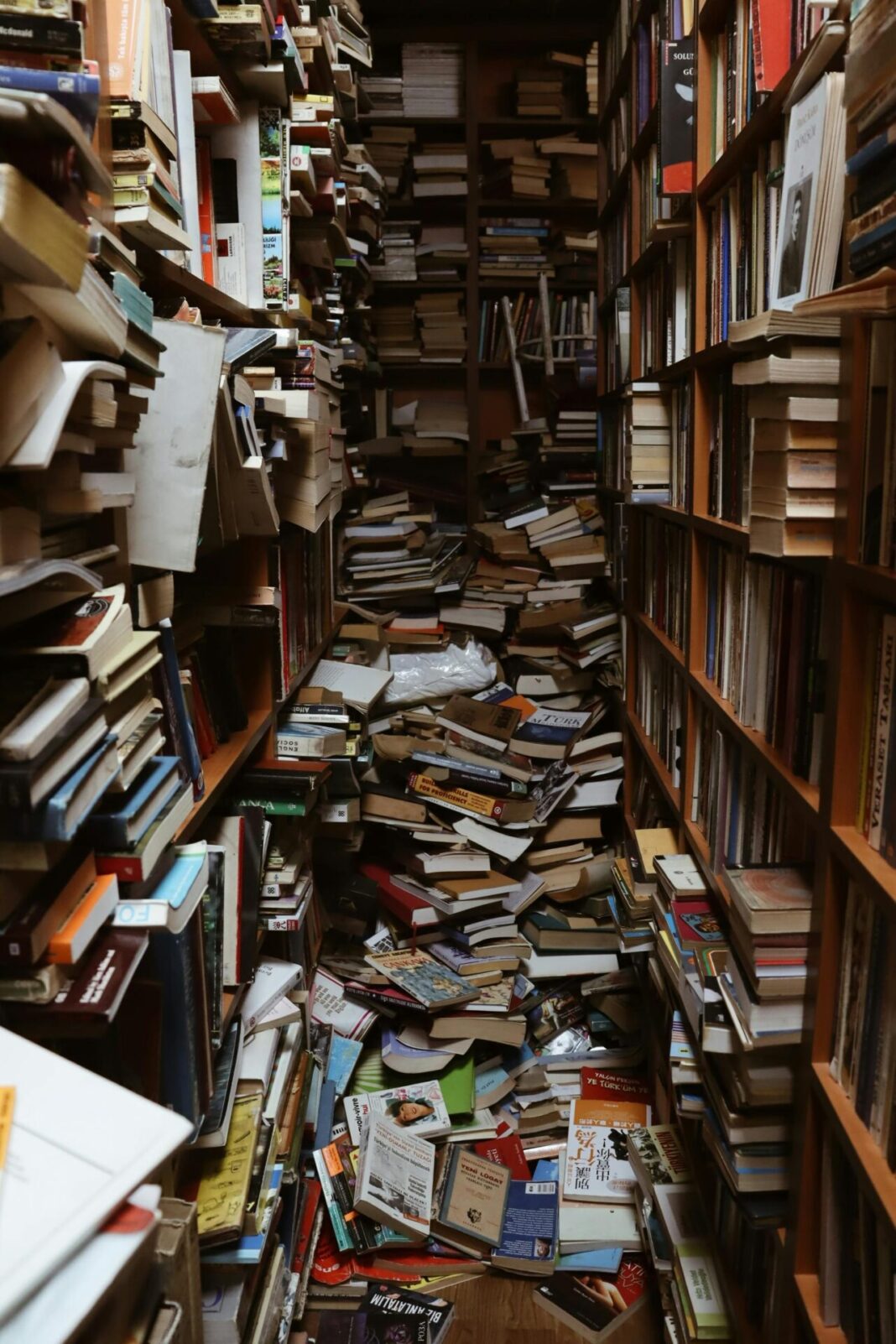

Quite without meaning to, I’ve found myself, in my half-constructed library, rereading the German cultural critic Walter Benjamin’s delightful little essay “Unpacking My Library.” Benjamin seems to have his bookcases already set up and is involved in the not-unpleasant process of moving his books from their boxes to their position on the shelves. His room, like mine, is chaotic, a “disorder of crates,” though its dominant mood is not frustration but “anticipation.” The present disorder is a temporary prelude to a future order.

Or is it? One of Benjamin’s points in this essay is that the library of a collector–and I guess I am one–is never all that orderly:

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories. More than that: the chance, the fate, that suffuse the past before my eyes are conspicuously present in the accustomed confusion of these books. For what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order?

I have not accumulated my books, that is, through some sort of systematic process; I’ve gotten them in fits and starts, and much of the pleasure of acquiring them has been the arbitrariness of the whole thing. Like many people, I’m sure, I keep a list of books I’d like to buy, but at least half the time I go to the used bookstore I end up coming home with something that’s not on the list.

But even if my process were more systematic, there’d still be an element of chaos in my library, because there are simply too many books for me to buy, or read, or fit in my basement. A genuine collection is always going to be idiosyncratic, because a genuine human being is always idiosyncratic–and what is a collection if not a projection of the collector’s selfhood? Just as my experience of the world is always a somewhat arbitrary slice of the whole of reality, my library will always be a somewhat arbitrary slice of published reality. The only alternative is to own Jorge Luis Borges’s Library of Babel, which contains not only every book that’s been published but every book that could possibly be published (and probably some that couldn’t). The idea is not really that appealing, because such a library would be by its very nature impersonal–not the sort of place I could retreat and return to myself.

So every library is a sort of chaos to everyone but its curator. And perhaps to him, too, in the same way that we are always mysteries to ourselves. Anyone who has ever tried to organize a library knows what I mean. Any particular organization is bound to run into titles that frustrate the schema. That’s because books contain multitudes, and organizational schema strip multitudes down to individuals. So chaos always remains.

I think ultimately what Benjamin is saying is that the library is in a state of apparent chaos that nevertheless tends to a sort of semi-audible harmony. The collector who buys books from catalogs learns to speak a new language: “Dates, place names, formats, previous owners, bindings, and the like: all these details must tell him something–not as dry, isolated facts, but as a harmonious whole; from the quality and intensity of this harmony he must be able to recognize whether a book is for him or not.” But the harmony of a library is the harmony of twelve-tone music; many notes will seem out of place to the untrained ear–and of course, only the owner of the library can have a trained ear.

This sort of harmony represents a middle ground that gives the home library its potent resonance. On the one side, we have the generalized chaos of the world, particularly the online world in which most of us regrettably spend much of our time. Our library offers us, along with its quiet and whatever aesthetic qualities we bring to it, order: it is a world that makes sense to us, a world in which we can make a home.

But the order of the library, because it’s always somewhat chaotic, resists the technocratic order of a world increasingly ruled by inhuman algorithm, a world that would attempt to remove all mystery (read: chaos) in its quest for technical perfection. Ebooks, I suppose, could offer a perfectly orderly library, with everything that’s ever been written instantly available to us. But I just can’t bring myself to buy an ereader–whatever library I accumulated on it would no longer be a projection of my selfhood, which demands limitation and embodiment and a certain level of chaos.

Maybe, in the end, a home library does what a long-inhabited home does: charts a middle ground between the chaos of the world and the hyper-rationality of modernity. It brings us order, but not too much order. There’s room for more, and there’s always some cause to reorganize–and yet it’s a familiar space, a place to find ourselves and to know ourselves. I hope mine is unpacked and assembled by the time this is published.

Image via Pexels

Update: Still not unpacked!

I am in the process of downsizing my library, in anticipation of retirement in a few years and a move to a smaller space. It is a hard thing to do and one must be ruthless, in a sense. My current plan, which has only been in place for a few months, is that with every new (to me) book that I acquire, I sell, give away, or donate two. This has worked pretty well so far. I have far more books than I’ll ever be able to read, so I feel like many of them could be better enjoyed by other folks rather than just sitting on my shelves.

I’ve gotten more selective in what I buy as I’ve gotten older, partly out of space concerns, but also out of better judgment. I seldom if ever do the “Hey look, that’s cheap, buy it because you might read it someday!” thing that was a common practice in my younger days.

I am treasuring the last paragraph and will copy it into a journal for just such remembrances.

Comments are closed.