On nothing more than a whim, my wife and I began to explore the world of estate sales a few years ago. Living in an older (by US standards) city like Pittsburgh, there is no shortage. We typically review a weekly list of available sales online and set our course for Saturday mornings. Many are homes that have sat vacant for several years since the passing of their owners, some are in so-called “McMansions,” although these, to our eyes, are the saddest and usually least interesting, as it often seems that the owners have literally walked away from their world, leaving everything behind: entire wardrobes of clothing, framed pictures of years of family photos, furniture, garages full of tools, and all of the more common items associated with maintaining a contemporary household. Nothing ever appears to be more than a few years old. See enough of these and one begins to get impressions of nasty divorces or job relocations in which people are just trying to shuck everything and start over, but one is never quite sure.

Such homes are less interesting than the riches often found in the older abandoned homes. These riches can be found on shelves thick with dust, in bookcases, or in unmarked boxes tucked away in the corner of a basement and include the remnants of decades, if not sometimes centuries, of people and memories long-forgotten. The latest treasure I found as I was ready to leave a house; the house had obviously set empty for many years while the family or executor of the estate got around to emptying the contents and preparing for its sale. Painted woodwork was worn thin, floorboards creaked, and the musty odor of age was apparent. On the corner of a well-worn buffet was a small, plain and faded cream-colored cardboard box with ragged edges, appearing to have started life containing fine stationery.

Opening the box revealed a handful of letters, handwritten correspondence between Anne Murray and her would-be suitor, Lee Whalen. I sensed the possibility of a rich slice of history and eagerly paid the $3 asking price for the box, anticipating the chance to explore them more fully at home.

The letters contain nearly a year’s worth (1928-1929) of correspondence between the two, with Mr. Whalen’s letters sent from the Hotel Times Square (now The Michelangelo), New York City, where he apparently stayed during his various trips on business while she remained living and working in Pittsburgh. The hotel stationery shows a graphic image of the hotel with the words, “Absolutely Fireproof” under the picture.

The nine intact envelopes include Lee’s letters to Anne and what is presumably her reply to same, although why her reply letters would have made it back to her is not clear. Perhaps these reply letters were merely drafts of letters she revised and actually sent. What is clear is that the exchanges reflect a dance of desire between two people nearly one hundred years ago, with several fits and starts along the way. Neither of their ages is apparent. Lee pledges his undying affection for Anne as he moves from job to job, culminating in a hoped-for engagement, which Anne kindly but firmly rebuffs; apparently Lee had a gambling and drinking problem. She writes (quoted here as written), “Dear Lee, Your letter was received and I was delighted to hear from you. Now that you have (may I say reformed) I hope you will live up to your good resolution. If you can measure up to my standards, and you know what they are, I shall be glad to renew our friendship. Unless you can promise to give up liquor for good, I do not want you to come back. I could not stand a repetition of what has already happened. Saturday and Sunday are yours. I am breaking a previous engagement for Sunday. I will be expecting you at eight o’clock on Saturday and hope that at that time we will be able to straighten out matters and begin all over again.” We can never know if they ever “began all over again” and eventually married.

Holding the letters was a delicate experience, noting the brittle nature of the paper, being careful not to let them tear at the aged folds, and yet the blue ink, obviously done with a fountain pen, was as clear as if it had been written yesterday. The penmanship of both individuals in cursive style was remarkably pristine.

It is a common conception that investing in such a process, even for those who were once taught cursive writing and the art of penmanship, has been lost to the keyboard, its expediency crowding out the careful and thoughtful work of longhand. Maybe something is gained by this efficiency, but Mark Helprin, in his novel, The Oceans and the Stars, describes his protagonist’s receipt of a letter from his lover while at sea thusly: “It was on elegant but plain stationery—cream on the outside, a Tiffany-blue envelope lining, cream papers, hand-addressed and written, with a floral stamp. And yes, her perfume was strongly apparent, so much so that he spent a few minutes before he opened the envelope breathing in deeply to catch the scent, eyes closed. Then he opened it. Just the handwriting was as seductive as anything by which he had ever been seduced.”

The record of Lee and Anne’s correspondence ends abruptly, with no final answers to the many questions raised in their few exchanges contained in that crusty cardboard box. Did he succeed in his “resolution” and finally measure up to her standards? I have searched unsuccessfully for any record of either of their lives, and yet from this happenstance on a Saturday morning I am granted a brief glance into a fragment of their lives. Historically, the letters between John and Abigail Adams come to mind, along with many others, and provide the reader with appreciation for the depth of their relationship perhaps best understood only through the medium of those exchanges.

I know it has been many years since I received a handwritten letter from anyone, or in fact sent one myself, yet my wife continues to labor long and lovingly to write notes of hope, forbearance, and love. I can open them from years ago, read them, refold them and recall the circumstances under which they were written, remembrances of times of great struggle and great joy, pieces of living history. Recently, I renewed decades-old friendships at my college reunion, and the memories shared there will certainly offer opportunities to nurture those relationships through the touch of pen to paper.

Perhaps it is unfair to elevate the status of a handwritten personal note or letter above an expedient email or other keyboard-produced content. Perhaps, but I suggest there is palpable pleasure in opening a note or letter that has arrived by mail or been tucked under your pillow. The weight and texture of the paper add to the anticipation that this is someone who took the time and thought to convey a message to you alone. When the message arrives in fountain pen ink, as with Lee and Anne’s letters, one can almost feel the spread of the ink as the nib glides across the paper and sense the working of the writer’s mind to organize and communicate the message.

These considerations will no doubt be considered hopelessly archaic by those of certain generations, where “instant messaging” is the default mode, but I for one will dig out my fountain pen, ink it up, and write a letter to a friend, knowing that it will be welcomed with special affinity and perhaps a little unexpected joy.

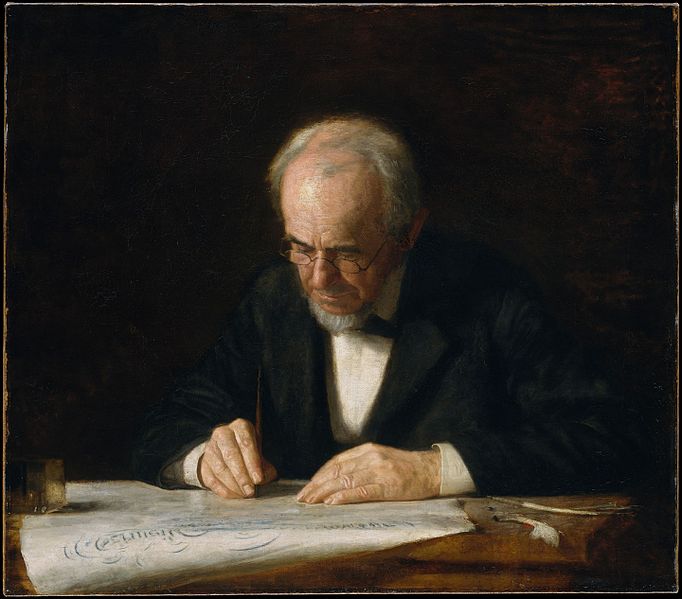

Image credit: Thomas Eakins, “The Writing Master” (1882) via Wikimedia Commons

Dear Art,

What a lovely essay! I love fountain pens and handwritten correspondence. Thankfully, I have many lovely friends who do too, and I often owe them letters! Thank you for sharing Lee & Anne’s story, you gave me a chuckle.

Yours truly,

Madeleine

Thank you for taking the time to read my essay, Madeleine! I’m so glad you enjoyed it. By the way, in case you read this reply and are curious, there is a quite a few fountain pen collectors (aka “addicts”) who regularly post reviews of fountain pens, inks, and related ephemera. I confess I have become one of them. Best to you!

When in High School (1962-1966), my hometown supported a Ben Franklin Five and Dime Store (now defunct) which carried not only red and blue plastic dip pens, but bottles of ink which had a small cup at the top of the bottle for dipping. I discovered them, loved them, and made good use of them (but any jottings have been lost for a good half-century now.)

Later on, I discovered fountain pens, refillable from the same aforementioned bottles, but state-of-the-art meant I would soon have shirt pockets blotched by leaky pens, alas.

Then came the age of the cartridge fountain pen, and I soared.

Early in this Century, I taught (briefly, three years), an adult Sunday School Class, and wrote out all my lessons on a 8X11 legal pad with my ancient trusty (cartridge) fountain scribbler.

Here and Now, I carry about a 5X6 notebook with a fountain pen of variegated colors (a gift), and transfer notes daily into a diary/journal with another fountain pen of sturdy black ink.

I do not post to the “cloud”, nor type out and print in Times New Roman. Silly of me. But it is immune to a high-altitude EMP blast or intense solar flare.

But perhaps my great-grandchildren (some of whom are already on the scene) might fine something interesting in my ramblings down the road. If not, they always have the fireplace and the garbage can to comfort them.

David, thank you so much for enjoying my essay, and for a little insight into your own experience. It would be sad if your “ramblings” were lost over time; maybe consider burying them in a metal box in a wall of your house somewhere!

Best to you!

Art

Your writings, always, are a pleasure to read. You connect people, at least me, with palpable memories! I still have years greeting cards stashed away that have been sent to me by my wife and children. Not only were the pre-printed thoughts carefully chosen, they earmark many special times in my life. Furthermore, they are filled with special, albeit brief notes filling the blank portions of the cards. The story of Anne and Lee remind me of our son during his college years. He and a girlfriend decided to forego texting and emails in favor of writing letters in cursive to one another. I recall his descriptions of how much more personal the letter writing experience was to them. Yet again, I traveled coast to coast with our son. Stopping in western national parks gave us an opportunity to see Native American hieroglyphics carefully, laboriously inscribed on stone walls. No doubt, hundreds of years ago the meanings and symbolism were important enough to take a writing implement in hand to carve or dye a message for the eternities.

Lastly, a contemporary parallel. As a psychologist, teacher, mentor, even as an administrator I have always found an eye to eye conversation so much more meaningful to the conversants. Hearing intonations, observing body language, sensing emotion,…add richness, depth to conversation, not to dissimilar to the visual responses of viewing someone’s handwriting and the mental images handwriting can conjure up. Today I often hear people say, “I talked to so-and-so today…,” when there was an audible word exchanged. The “talking” was actually a text or email received on a small cell phone or computer screen. I can ask my phone to read my last message, and in the same emotionless droll the phone can tell me to pick up groceries or of a tragedy that has occurred. I favor at least, picking up a phone, hearing a voice, and really talking. I cherish lunches and dinners with family, friends, and colleagues learn what’s happening in their lives or why it’s relevant for us to be sitting and enjoying a meal together.

I’m afraid our progress has taken so much of the sensory experiences of communicating out of the picture. Less and less is there the aroma of a perfumed envelope, the texture and design of special stationery, the sound of voices, the scrawl of a pen, or real time images of looking one another in the eye part of how we convey meaning.

Thank you and best wishes my friend.

Thank you for the kind and thoughtful comment, Lee! Your vignette about D. and his girlfriend’s “experiment” in letter-writing provides me with another insight into a remarkable young man. You can tell me more, soon. Take care.

Comments are closed.