“No man of his age was better suited to introduce the Christian faith to the longtime residents of New Spain’s frontier.”

Much might be said about the neglect of the history of the American Southwest. Some might even assume this history only stretches back a few hundred years. Indigenous historians would balk at this point, but it is important to ask how much attention is really given to the Spanish missions especially during the era when the American Revolution was getting underway. Perhaps part of the dilemma is the dicey relationship between the native peoples and the missionaries. Even the most famous of these priests, Junipero Serra, is not beyond reproach in his relationships with Indigenous peoples. Because our attention is often drawn toward Boston and Philadelphia in our U.S. history books’ coverage of these decades, new histories that illuminate the history of the Southwest are a welcome gift. This is particularly true with regards to ecclesiastical history.

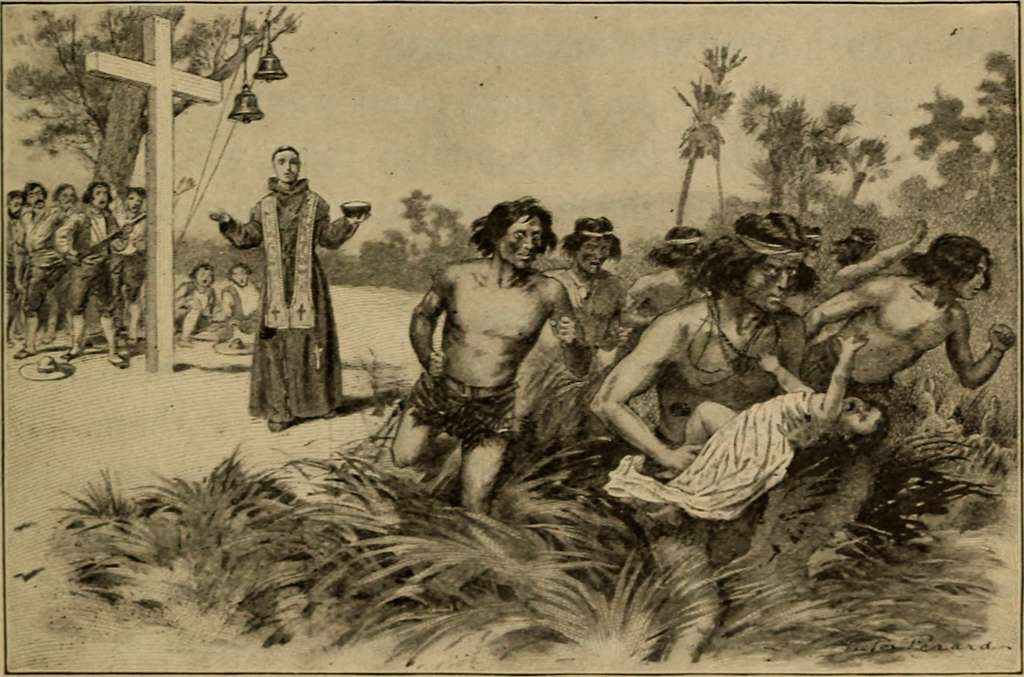

So thanks are due to Jeremy Beer, whose Beyond the Devil’s Road: Francisco Garcés and the Spanish Encounter with the American Southwest introduces us to a forgotten priest, the Franciscan Francisco Gárces, who he claims is a pioneer in traveling through uncharted territory before any other European. While reading about Gárces’s travels in the Sonoran desert, stumbling upon discovery after discovery, I could not help but picture scenes of the movie The Mission, hearing the melody of Ennio Morricone’s “Gabriel’s Theme” in the background. However, unlike Gabriel’s colorful jungles and waterfalls of the Amazon, Gárces’s journeys across scorching, desolate deserts might be more reminiscent of films like Lawrence of Arabia or a John Ford western like The Searchers, if we are comparing cinematography.

Gárces is a man ahead of his time. In most cases, he advocates for Indigenous autonomy and decries any forms of coercion. He had a sympathetic understanding of cultural differences, which oftentimes leads to friendly relations between him and the native peoples. In fact, direct contact with the diverse peoples of the Southwest led to his evolving views. Furthermore, notes from his associates point out that “Francisco Gárces is so well suited to getting along with the Indians and going among them that he seems to be very much like an Indian himself.”

Other Spanish Catholic missionaries like Anza, Serra, and Kino may be more famous, but Beer asserts that “Francisco Gárces, who explored more of the Southwest and had greater contact with more of the peoples of the region than any of these better-known figures, deserves to join their ranks.” This is the core thesis of the book. And his meticulous focus on primary sources, many being Gárces own travelogues, helps to make this case.

The book begins far away from the Southwest in Spain, detailing Gárces cultural upbringing. Gárces, and Serra for that matter, are latecomers to the early modern Spanish Catholic missionary efforts. Beer reveals that Gárces and his contemporaries were inspired by the Franciscan mystic María de Ágreda’s Mystical City of God, the pioneering missions of Francis Xavier, and the tragedy of the twenty-six martyrs in Japan, among other missionary stories. However, these tales are centuries-old when Gárces was a boy. In addition, the Franciscans were stepping into the mission field following the Jesuit reductions (again, fans of the film The Mission will recognize the active removal of Jesuits across the globe). Gárces was roughly contemporary with Benjamin Franklin, so like Serra, he was a man of the eighteenth century. The bigger question is why Gárces’s missionary travels are so important for the Spanish missionary system hundreds of years after 1492?

Part of the issue that the Spanish dealt with is the complexity of the relations with the various Indigenous groups in the Southwest. The Apaches, for example, are notorious for raiding the missions and stirring up conflict with other tribes. In fact, Serra’s success in California is attributed to not having to deal with them, as opposed to Gárces and his predecessors. Coercive efforts by Spanish soldiers and sometimes priests led to various Indigenous uprisings―oftentimes the priests were the ones to stand between rapacious soldiers and Indigenous women. Moreover, as the book’s title suggests, navigating the so-called Devil’s Road is no walk in the park. However, because of his more open view toward Indigenous cultures, Gárces is ultimately helped by groups like the O’odham and so gains a better understanding of the geography. Gárces’s pioneering travels inspire Spanish headquarters to chart more of this territory (though Gárces’s writings are notoriously sloppy, so he needed an editor to make sense of them).

Beer’s account complicates the history of the Spanish missions. Detailed histories reliant on primary sources often paint a picture where the characters appear grey. The book does not waste time rewriting the history through a lens of colonizer and the colonized, terms that the historical actors would not be familiar with. These terms might be helpful for us to describe the power relations between the Spanish and the many Indigenous groups in this region, but Spain’s claim to this territory was often on shaky ground. Spain is hardly a poster child for a successful colonial power, especially in the eighteenth century. In fact, the book ends with not only the rise of the United States as a new type of nation state on the other side of the coast, but with the failure of the Spanish project. Indeed, one gets a sense that things go awry because of naivete among the Spanish and their grand schemes for their missions. However, Beer illustrates that what causes the ultimate demise of the missions are circumstantial events―sometimes the case being the wrong person being in charge at the wrong time or promises that were made that were not kept. Spanish Catholic ideological designs ultimately succumb to the contingent nature of history and the folly of miscommunication.

Beyond the Devil’s Road is a large book that oftentimes reads like a travelogue, and to Beer’s credit he narrates it in a way that motivates a closer look at Gárces’s travels. The foreboding sense of doom climaxes at the last chapter―things go from bad to worse quickly in the so-called tragedy of July 1781. However, before having a chance to mourn Gárces’s murder by the people he loved, Beer reflects that some descendents of the Indigenous people that Gárces ministered to maintain a commitment to Christianity into the present. He closes the book with this legacy. Beer declares: “If Christianity exerted no attraction for the O’odham, it should have died. But it didn’t. The O’odham themselves kept the friars’ faith alive.”

Native American Christianity might be one of the most important trends of recent scholarship on the relationship between the Spanish and the Indigenous people they met. Again, instead of seeing this relationship in binary ways, the sources illustrate that sometimes the Christian message becomes something that the Indigenous people make their own, irrespective of the actions of the Spanish, at least once the Spanish fade away from the scene. Beer notes that the “sunbaked, stark-white churches” are the physical manifestation of Gárces’s direct legacy displayed throughout the Sonoran Desert. In fact, Gárces provides a model of interculturality as understood by such Catholic thinkers as Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, who lived this “ideal in action more than any other missionary of his time.” Considering Gárces’s legacy, this is an intensely local story with far-reaching implications, and the book is well worth the time if you have interest in the history of the Spanish mission project, Indigenous history and culture, or Christian history more broadly.

Image Via: GetArchive