“Your posture looks pretty good. And it doesn’t matter—that’s the whole point of my book. It’s fake news,” said University of Pennsylvania professor of history Beth Linker in an interview about her recently published book Slouch: Posture Panic in Modern America. Although later in the interview she does say that she is not a “posture denier,” noting posture treatment can be helpful in managing back pain, she doesn’t believe there’s enough evidence to support the idea that posture has had much of an effect on otherwise healthy individuals. Linker’s categorical denial of the importance of posture is surprising, not least because it is at odds with statements she makes in her own book. In the book, she states that she is not going to take a stand on the physical effects of posture: “I make no claim about the realness of the epidemic or the degree to which poor posture was and is debilitating.” There’s a disconnect here. The incongruity of what would seem to be mutually exclusive statements—the “fake news” interview statement and the “making no claim” book framing—raises many warning flags. The statements are, however, not as entirely incompatible as they first appear. Linker may not explicitly argue in Slouch that the importance of posture is “fake news,” but it is the book’s implicit central argument.

So how did we get to this strange place where an Ivy League professor wrote a book whose main point is something she says in the book she is not even going to address? This convoluted approach is the book’s biggest weakness, and it is worth exploring, but first, it is helpful to have an overall understanding of Linker’s work, which actually does contain a number of thought-provoking ideas and interesting historical examples, including the strange practice of subjecting college freshmen to nude posture photos.

Many people involved in the posture sciences in the early twentieth century believed slouching lay at the root of a good many societal ills. Slouching was believed to increase the pressure on internal organs, inhibit the full use and development of human lungs, hinder proper digestion, and increase the risk of organ prolapse. Additionally, slouching was believed to tax the human body more than proper posture, sapping the body of necessary vitality for other tasks and leaving it more vulnerable to disease. Those concerned with posture thus saw slouching as contributing to problems as wide ranging as tuberculosis and civil unrest. Linker traces the origins and life of this “posture panic,” as she terms it, in the United States over the past century. In Linker’s analysis, the posture panic rose to its zenith in the early to mid-twentieth century, with posture crusaders buttressing their case with anthropological and archeological findings and technological measuring tools.

Linker explains that those fomenting the posture panic drew from nineteenth-century archeological discoveries that suggested (as Darwin had postulated) that bipedalism was a precondition for other valued developments in human evolutionary history, such as larger brain growth, speech, and even civilization. Some believed that bipedalism left humans uniquely vulnerable to other health challenges, arguing that the spine was not meant to be a column but a girder. Others believed that the human slouch was the result of over-civilization, with people at all strata of American society facing pressures and circumstances that the human race had not evolved to endure, whether that was repetitive stress injuries for the industrial laborer or the slouched backs of the more sedentary office professionals hunched over their desks. Both of these interpretations provided support for the belief that the posture of the modern human needed to be improved, whether it was to strengthen an inherently compromised human body or to help the human body withstand the challenges of industrialized life.

Posture improvement advocates found educational institutions an essential place to combat this perceived poor posture epidemic by surveilling and straightening students’ backs. Jessie Bancroft, founding member of the American Posture League (APL), was one such posture crusader, and in 1913, she published a book detailing home and school approaches that could be used to improve the posture of the country’s little ones. One strategy Bancroft outlined, based on her own experience working with schoolchildren, was testing student posture at regular intervals and tabulating the results into a passing-rate percentage. She told of one highly motivated class that desperately sought a 100% score, but a single student’s poor posture kept the class from achieving perfection. The poor-postured student’s peers were so frustrated that after school they “waylaid” and “pommeled” the poor boy. Bancroft described the incident as humorous but did not elaborate as to whether inflicting such bodily harm ultimately helped the student’s posture.

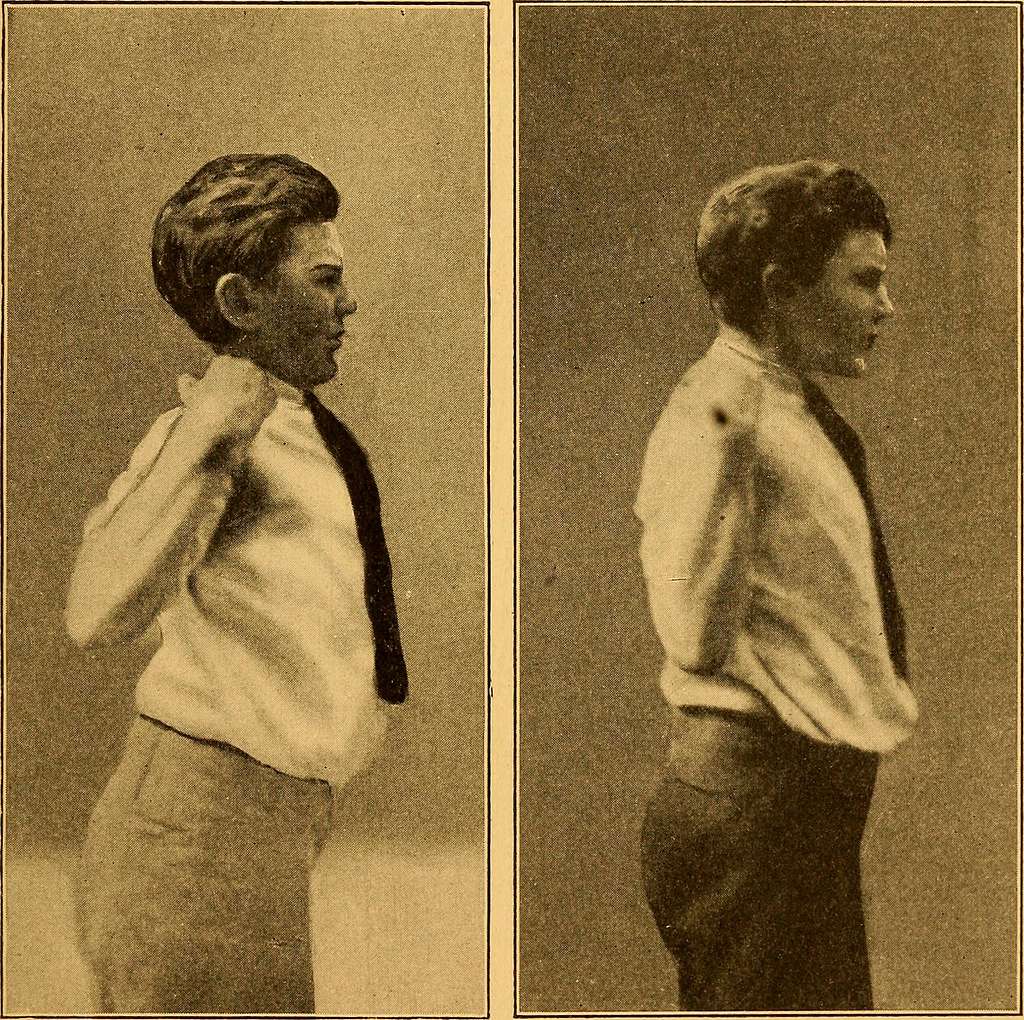

Linker examines in depth the role that educational institutions played in pioneering efforts to monitor, improve, and track students’ posture development. Different technologies over time were seen as essential to facilitate the posture crusade. The schematograph, a machine pioneered by APL member Dr. Clelia Mosher, allowed operators to trace posture profiles onto sheets of paper and create a standardized representation of posture and perceived posture deficiencies. The schematograph was increasingly replaced by cameras as photography became cheaper. The adoption of cameras was also spurred on by criticisms that posture science lacked scientific rigor: the practice of taking posture photos in the nude was considered more accurate. Some even tried to enhance measuring capabilities further; for example, the Wellesley method included affixing “light aluminum pointers along” the students’ “spines and sternum” to better track the spinal path in photographs.

For a number of years it became mandatory for many incoming college freshman to pose nude for posture photos. In the second paragraph of Slouch, Linker contends that “by the mid-twentieth century, most schools had adopted camera photography to assess human posture, requiring students to pose nude or seminude for the pictures,” and that it had become “a ritual on nearly every college campus in the United States.” There is no footnote for this assertion, and Slouch does not make any effort to comprehensively chart where and when this practice took place. This broad assertion does not match the evidence Linker presents in the rest of the book, which indicates that the practice primarily took place among northeast educational institutions, particularly the Ivies, Seven Sisters, and a handful of other schools. David Yosifon and Peter Stearns’ lengthy article on what they call the “posture wars” says it is hard to know how widespread the school practice of measurements and photography was, and while it was most rigorously practiced in the Northeast, it likely did not take place in the American South. Without more evidence from Linker, her contention that the posture photos were normative on nearly every US college campus beggars belief.

Yet it wasn’t just educational arenas where posture concerns took hold. As Linker makes clear, where postural improvement advocates paved the way, corporations and entrepreneurs quickly followed, hawking new products for consumers as well as for corporations seeking to boost workers’ productivity. The financial aspect of posture improvement is difficult to disentangle from the scientific aspect; a founding motivation of the American Posture League was to design or approve of products that were deemed posture friendly. Not surprisingly, those in the business of selling products were incentivized to see the human body as inherently deficient and in need of outside commercial intervention.

At the end of WWII, posture campaigners lost some of the heft behind their claims about the importance of posture because increased American prosperity and the spread of medical developments such as antibiotics and vaccines reduced concerns about tuberculosis and other communicable diseases. Worry about posture did live on in the early Cold War, as strengthening American spines (both literal and metaphorical) in order to defeat the Soviets was seen as an important goal. Universities continued to take posture photos, but by the 1970s, they discontinued the practice amid increasing pushback from students (especially women and disability rights advocates), as well as decreasing general concern about posture and the decline of in loco parentis, which had provided some of the justification for the schools to take such an involved role in improving posture.

The posture photos did not just disappear though. They were held in university archives. But it became increasingly clear that storing such sensitive images (especially of alumnae) was a liability. In the late 1970s, Yale PhD student Gretchen Dieck turned to the posture photos held at Smith College as a resource to explore whether spinal deviations of young women increased the risk of back problems or other musculoskeletal challenges later on in life. Dieck’s research also relied on surveys sent to Smith alumnae, which raised the alarm among former students, since many of them thought that the posture photos had been destroyed. Dieck was able to assuage enough concern to gather responses from the cohorts she was studying to finish out her research, finding that although a majority (70 percent of those examined) had what would be considered postural aberrations, they did not correspond with spinal pain or herniated disks later in life. Dieck’s communications with Smith graduates, however, had raised the specter of the sensitive pictures to a large swath of alumnae, who continued to express concern about them to the school. Smith University administrators decided soon after to destroy the photos.

Even as many universities destroyed their nude posture photos over the next few decades, concerns about the images remained. On January 15, 1995, a salacious New York Times Magazine cover story by Ron Rosenbaum brought the photos into wider national consciousness, creating a “posture photo scandal” over nude photos being held at the archives of the Smithsonian that were taken by the constitutional psychologist William H. Sheldon. Worried alumni of schools mentioned (and not mentioned) in the Rosenbaum story contacted their schools to express their displeasure with the photos, and some schools sent their archivists (some of whom had reservations) to the Smithsonian to oversee the destruction of the Sheldon photos connected to their respective institutions. The Rosenbaum story and its aftermath serve as Slouch’s opening hook, and in many ways they are the book’s driving focus and crescendo. Unfortunately, Linker doesn’t get the details quite right.

Slouch’s opening paragraph says that those who opened the magazine “learned something surprising and sensational. Thousands of nude photographs, including those of prominent public figures such as George H.W. Bush, Bob Woodward, Meryl Streep, Hillary Rodham Clinton, and Diane Sawyer existed in the Smithsonian Archives, readily available for public viewing.” This is wrong on several accounts. Rosenbaum does not say that these high-profile figures’ photos were featured in the collection; he only mentions that these individuals had had their posture photos taken while they were students. Additionally, only Woodward’s undergraduate years overlap with any of the schools and years housed in the archive detailed by Rosenbaum, and even Woodward’s 1961 class of entry was not among those mentioned, so it was likely also not in the archive. Perhaps if you only looked at the cover of the magazine—which featured photos of a number of high-profile individuals when they were younger—you could be forgiven for thinking that nude pictures of these people were in the Smithsonian archive, but Rosenbaum never makes such a claim. And the photos in the archive were also arguably not readily available; Rosenbaum had to submit an application and wait three months for approval to view them.

Despite these errors, Linker does provide some interesting corrections and context to Rosenbaum’s work. According to Linker, Rosenbaum mistook the Sheldon photos as representative of the longer-standing practice of posture photos and conflated the two approaches. Sheldon did at times collaborate with posture scientists to facilitate picture taking, but he instead used the images for his own somatotyping research, which was not concerned with spinal deviations but used a different set of criteria to determine the constitution of the students’ body, which he believed determined “a person’s inherited and unchangeable personality and mental makeup.” Sheldon was eugenicist in his approach, believing that body composition represented inherited traits, and therefore it was necessary to promote the reproduction of those who considered part of the superior race. Linker insightfully shows that the posture scientists and Sheldon should not be lumped together.

Linker concludes the book by exploring more recent concerns about posture, focusing on the idea that poor posture contributes to back pain as well as the oversimplistic ways in which anthropologists and body-work specialists have argued that hunter-gatherers and others with “optimal posture” don’t suffer from back pain. Linker argues that it is hard to dispel the idea that bad posture results in back pain and notes that the destruction of the Sheldon photos closed off an avenue that could have been used to study the matter longitudinally and help determine the validity of the postural science claims.

On the whole, Linker has written a generally accessible monograph with thought-provoking arguments as to how and why posture concerns became as widespread as they did in the twentieth-century United States. For an academic text, it is highly readable. Slouch would make for an interesting book for discussion in a graduate seminar class, not just because of the compelling examples Linker examines but also for the many avenues of inquiry left unfollowed.

As noted at the beginning of this review, Linker writes in Slouch that she is not going to stake a claim as to the “realness of a posture epidemic” nor to what extent “poor posture was and is debilitating.” Perhaps she hoped to sidestep exploring the possibility that the posture crusaders had some valid concerns motivating their actions; the book’s framing (and her subsequent interview comments about the idea of good posture being fake news) shows that she considers the claims about the importance of posture dubious. The very term “posture panic” (highlighted in the book’s subtitle) implies that worries about posture were the result of emotional and irrational concerns, not founded on any significant scientific reasoning. In order to prove that posture concerns were really just a panic, however, it is imperative to separate the wheat from the chaff: to what extent were posture concerns based on physiological flourishing versus some political or social zeitgeist? If posture science claims had validity, then maybe there wasn’t a posture panic. Or maybe it was a legitimate problem that ended up being mishandled because of the inherent reality that you can’t impose the values and practices of intact moral communities—communities that haven’t been decimated by modernity—through the apparatus of the biopolitical state.

Linker is in a tough spot. If she were to cede ground to the posture crusaders, she would have to admit that despite human variability, there are normative health outcomes that the general person should aspire to. That is not a claim that goes over well with most scholars in disability studies, so I can see why Linker would rather avoid it. Other scholars in the field would be much more supportive of Linker’s analysis that “the job of the posture scientist was to discipline the bodies of the students so that these young adults would fit societal demands, not to have society fit them.” I can appreciate Linker’s desire for twentieth-century elite society to be more accepting and accommodating of those with different appearances and abilities, including people with significant postural deficiencies. I can also agree with Linker’s characterization of many aspects of the posture crusaders of the twentieth century. I came away from her book (and from the other reading I did in order to contextualize her work) believing that posture crusaders overstated the importance of posture, that postural scientists’ hyperfocus on narrow aspects of human health combined with the surveillance and disciplinary environments of schools led to some strange, humiliating, and even painful experiences. I can agree that it is difficult to even know what “good posture” is for each individual person, given the variety of human body types and abilities.

But even with this support for Linker’s analysis, I can’t help but think of Katharina Schroth, a contemporary of the posture crusaders in Dresden, Germany, who could have also been accused of disciplining bodies to fit people into society rather than having society fit them. As a child, Schroth suffered from a difficult case of scoliosis; her extreme spinal curvature meant that she would likely spend her life bedridden or in a wheelchair. James Nestor’s book Breath tells of how Schroth was not content with this prognosis, and taking inspiration from how balloons “collapsed or expanded, pushing or pulling in whatever was around them,” she wondered if she could do the same thing with her lungs to “expand her skeletal structure” and maybe even “straighten her spine and improve the quality and quantity of her life.” With dogged determination, the 16-year-old Schroth “would stand in front of a mirror, twist her body, and inhale into one lung while limiting air intake to the other. Then she’d hobble over to a table, sling her body on its side, and arch her chest back and forth to loosen her rib cage while breathing into the empty space.” After five years, she no longer had “incurable” scoliosis. As Nestor pithily notes, “she’d breathed her spine straight again.” Schroth would build on this method, establishing a clinic that helped countless people improve their spinal conditions, gain the ability to breathe deeply, and even walk, in the case of some who were bedridden.

Schroth’s approach actually shared a number of similarities with American posture crusaders, including using mirrors to help patients improve spatial awareness and cultivate healthier posture. One notable difference appears to have been Schroth’s more holistic integration of the lungs and spine into a symbiotic relationship. The American posture crusaders did see posture as enabling proper lung function, but Schroth found the lungs to be a powerful mechanism to get the spine where it needed to be in the first place. While the American posture crusaders may be easier to dismiss, Schroth’s story invites the question of what it means to truly take care of those with varying abilities. Remaking society to fit these differing abilities is not always the most charitable path; to do so simply normalizes helplessness, pain, and suffering while letting people pretend they care. Surely there is a path where we can support those who may not neatly fit expected outcomes while also fostering cultures that help humans achieve greater strength and vitality.

Ultimately, I can’t support Linker’s assertion that the value of good posture is fake news, not just because she never makes an attempt to prove it, but because her book ignores a whole host of evidence that supports the importance of posture. For example, Linker dismisses New York Times health columnist Jane Brody’s concerns for posture by saying that Brody contradicted “what some of the earliest medical critics of the posture sciences had demonstrated,” as if to say Brody was only reiterating beliefs that had been disproved. But Brody is actually citing more recent concerns about the importance of posture, including those by the physician René Cailliet, whose work appeared after the height of the posture panic and found posture to be central to human health. Brody explains that Cailliet argued that slouching could decrease “lung capacity by as much as 30 percent, reducing the amount of oxygen that reaches body tissues, including the brain.” Cailliet is not easily dismissed; it is telling that Linker ignores him.

There are other studies to point to in arguing for the significance of posture, but in the end, what is more important is to understand that posture is part of a dynamic and complex array of physiological developments and functions. Determining the exact role of posture is impossible, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t important for general human health. As Schroth’s example demonstrates, lung function influences posture, and posture influences lung function. Another example would be the way airways and orofacial development act on and are acted on by posture; they build off each other. The posture crusaders’ reductive treatment and surveillance proved too simplistic to account for this dynamic interplay. Linker’s failure to look more broadly at the importance of posture ends up reflecting the posture crusaders’ myopia rather than correcting it.

The point of invoking this oppositional evidence and exploring the complexity is not to prove beyond a shadow of doubt the importance of posture but to demonstrate that Linker’s dismissal of posture combined with her failure to engage with a whole host of countervailing evidence undermines her work. Linker ends up normalizing the wreckage of modernity rather than wrestling with it. Particularly, when informing the public on something regarding human health, it is critical to plumb the depths of the topic. To do otherwise makes the book and public engagement feel, well, a bit slouchy.

Image Via: GetArchive