In his introduction to a re-issue of William Dean Howells’s The Rise of Silas Lapham, Booth Tarkington explains that Howells, the father of American Realism, taught him to renounce his juvenile romanticism and embrace critical realism. According to Everett Carter’s definition in his Howells and the Age of Realism, the name critical realism is given to literature which “truthfully reports warped and maladjusted social relationships so that men may study and improve them.” Thus, the critical realist’s message builds upon social and historical continuities, for, to Howells, explorations of social structure are “the only novel opportunities left for fiction.” The Turmoil, the opening novel of the Growth trilogy (1915–1923), is Tarkington’s first success in the art of critical realism. He relies on the Howellsian “imitative faculty” to record the process of industrialization and commercialization in an unnamed mid-American city, an every-city, of the Gilded Age. Like Silas Lapham, The Turmoil probes the problem that faces Americans of little culture who have amassed great wealth. As New Money neglects high culture by succumbing to greed, and as Old Money loses its standing in society to these philistines, Tarkington wonders how America can save the contemplative life necessary for building a healthy culture.

Tarkington depicts industrialization through the self-made magnate James Sheridan. He is “the biggest builder and breaker and truster and buster under the smoke.” This smoke from the chimneys of Sheridan’s Pump Company permeates the novel. As Herr Favre, a businessman from Germany, points out while on a tour of the city: “There’s no white anything in your city…Smoke ef’rywhere.” Sheridan’s response of “you bet we got smoke” shows his wholehearted love of Bigness, portrayed in the opening pages of the novel as a giant worthy of worship. Bigness brags that “there shall be no clean thing about me,” and as a good disciple, Sheridan does its bidding. He is proud that his multiplying factories always produce smoke, because more smoke equals more profit. He names the smoke “Prosperity,” the chief virtue in his secular trinity alongside “Ambition” and “Progress.” At one point, he kisses the falling ash and blurts that it’s “good, clean soot; it’s our lifeblood, God bless it!” Not long after, Tarkington juxtaposes Sheridan’s gesture with his youngest child Bibbs’s reveling in his actual lifeblood, the “clean air” and “glorious sky.” Thankfully, the smoke has not vaporized the entire region, and Sheridan’s trinity has not inverted the localism, communitarianism, and tradition of the heartland.

The story of the New Money Sheridans interlinks with the story of the Old Money Vertrees who are the cultured family in the city. On the lot next to the old Vertrees country mansion, Sheridan builds his New House, which reveals nothing except that the Sheridans were rich. This vacuous description of the New House begins Tarkington’s discussion of the possibility of high culture coexisting with the New Money “barbarians.” Unlike the Vertrees who “know good pictures and…good books,” the Sheridans’ New House comes with a series of vulgarizations. For example, we view an eleven-foot-long oil painting of the Bay of Naples, a statue of a life-size Turk wearing a “gold turban” and holding “a gold-tipped spear” (which Sheridan later pulverizes), and an old picture of a “table and a watermelon sliced open…rouged-looking apples and some shiny lemons, with two dead prairie-chickens on a chair.” The aesthetics of the New House are a far cry from the worth of Old Money’s possessions. After all, the Vertrees have obtained a half-dozen original Landseer engravings, the embodiment of value and good taste. They are the custodians of a meaningful past being infiltrated by the defiling smoke of Bigness.

Throughout the novel, Tarkington spends a significant amount of time discussing the “ready-made” library in the New House. It symbolizes the division between barbarism and culture. Sheridan passes many hours each day in the library, but he fails to understand that culture is built on libraries. Instead of disseminating the best that has been thought and said in the Western world, these “big, expensive books, with a glossy binding,” resting on large, custom-built wooden bookshelves, make “effective decoration.” Sheridan expends no energy in the pursuit of knowledge, yet he enjoys the appearance of it when he hosts his rich friends. He has never touched one of the dusty books because he reads “nothing except newspapers, business letters, and figures.” He compares books to “bric-a-brac or crocheting.” He bemoans anyone, especially his family members, wasting time and effort on such nonsense. Tarkington uses his description of the library as a second living room and Sheridan’s utilitarian view of reading to highlight the fact that New Money philistinism, whether conscious or not, mocks serious culture and, by extension, the contemplative life. Participating in culture requires much more attention than erecting a cheap imitation of it.

Despite Sheridan’s attempts to disparage and discard serious culture, Bibbs develops a connection with Mary Vertrees who uncovers his “secret life” of contemplation. Contemplation, in this context, is an attitude of mind and a condition of the soul that fosters a capacity to receive the deeper reality of the world by engaging in high culture. Mary has a penchant for aesthetics due to her Old Money environment and upbringing centered on exercises in contemplation. Bibbs, on the other hand, has an innate inclination toward contemplation, as indicated by his reflection entitled “Leisure,” which advocates for a peaceful outlet for his mind and soul to engage the depths of reality away from “the roaring of the furnace fires and the screaming of the whistles.” In its initial form, his contemplation teeters on the verge of inner solipsism. With the proper guidance, however, he can transform his burning desire for a contemplative life into a fully formed appreciation of beauty. Above all, Mary is drawn to Bibbs’s anomalous disposition among New Money—an openness to her world of high culture. A case in point is the episode at the church in which Mary invites him to hear her friend, Dr. Kraft, play Handel on the organ accompanied by the choir. By virtue of her place in society, Mary relishes the beauty of music. But Bibbs, who had “no music in his meager life,” is also “swept away upon that mighty singing.”

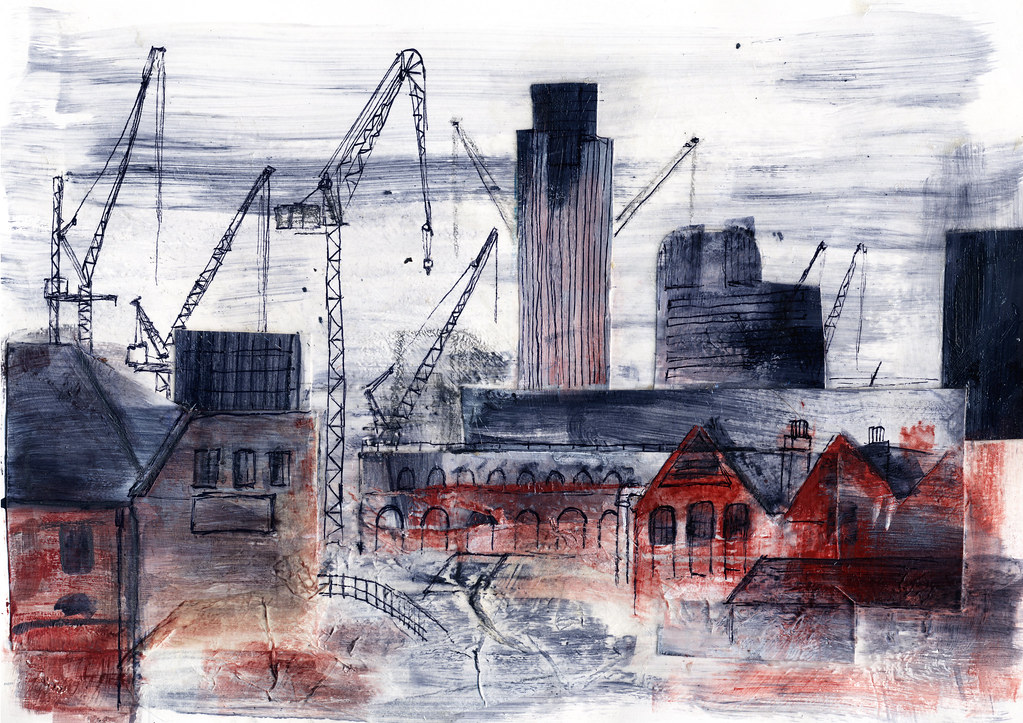

As Mary and Bibbs sit “intensely still” and listen to the “great sound all round about them,” they are so enraptured in the beautiful music that they are figuratively transported to “another planet.” When the “church grew dusky,” they lose track of time and space until the organist’s lamp produces “a tiny star of light” to reorient them. Mary’s analysis of the experience is that music “makes most things in our hustling little lives seems infinitesimal.” In other words, beauty expands our humanity as we reach higher for the infinite while industry shrinks it as we hustle lower toward the infinitesimal. The irony is that Bigness, which by its very name indicates expansion, reduces itself to the individual’s diminished ego. Bibbs writes in his notebook about the process of his developing a sensitivity toward aesthetics: “Everything that is beautiful is music, if you can listen.” Later, Mary introduces him to the visual arts by way of a local painter who sees through the smoke and paints beautiful representations of the city. He has a similar reaction to the paintings of “houses through a haze of smoke,” “smoky sunsets,” and “smoky sunrises” that capture the beauty in the turmoil. Bibbs, with his ears to hear and his eyes to see, engages, for the first time in his life, the depths of reality inaccessible to Sheridan who is cloaked in his cloister of smoke.

Bibbs’s initiation into high culture launches him into writing prose and poetry. These creative endeavors widen the rift with his father who expects him to join the family business. This specific father-son dynamic is Tarkington’s way of pushing the main conflict between industrialization and high culture to its climax. Put another way, action will either eliminate contemplation or contemplation and action will have to forge a new connection. Upon finding and reading his son’s reflection on Midas and the rooster, Sheridan deems Bibbs a fool, crumples “the sheets into a ball,” and deposits “it (with vigor) in a wastebasket beside him.” At dinner that evening, he strongarms Bibbs into dropping his potential career as an artist by reminding him who is boss: “Midas can eat rooster, but rooster can’t eat Midas.” Once again, Sheridan applies his Midas touch to get his way, but will this pressure produce more turmoil in the Sheridan family? More turmoil is a real possibility. He is already responsible for his eldest son’s death, his middle son’s alcoholism, and his daughter’s elopement.

Succumbing to the pressure of his father, Bibbs agrees to work as a low-level employee on the assembly line in the factory. Unexpectedly, he enjoys mindlessly working at his machine station. His imagination wanders and his writing intensifies because the rote bodily function frees his mind. He writes in his notebook that manual labor permits “your mind [to] dream while your hands are working.” He also writes that he would not be able to live a life of contemplation “if [he] had to scheme out dollars, or…add columns of figures.” After his father discovers this entry, Sheridan places his son in an executive position where he only deals with dollars and figures. Mary tries to encourage him to defy his father and pursue his budding life as an artist, but her intervention cannot change his fate. Bibbs has no other option except to grasp the role of business leader. Yet he has proven his leadership and executive abilities by buoying the Sheridan family from the moment his eldest brother Jim died at the factory. His future as a businessman is guaranteed when his father acknowledges that “a year from now…he won’t know there ever was such a thing as poetry.” According to Sheridan, Bibbs is no longer a “lummix” (sic), but according to the role he plays within the family structure, he never was a lummox.

The events in Bibbs’s journey epitomize the tussle in modern America between industry and art. Although Tarkington has been accused of sacrificing the artist for the sake of capitalism by having Bibbs become his father, this commonplace analysis of Bibbs’s maturation needs more nuance. His becoming a businessman is not a conversion to his father’s religion of Bigness. It is a melding of the contemplative life of the artist and the active life of the businessman. The key to this view is recognizing that Bibbs is not a first-rate artist, and even with years of training and practice, he will probably be middling at best. Earning a living from his art, as Tarkington did, is not an option for him. Even so, he is a competent businessman who can still be a guardian of high culture. Unlike his father, he offers his city hope. He demonstrates that other New Money moguls can acquire good taste with help from cultured stewards like Mary. Not all of them will be barbarians like Sheridan. And several of them may even become patrons of the arts, endowing libraries, museums, and universities.

Tarkington solidifies his vision of a prosperous and cultured America in his penultimate scene. Bibbs envisions the American pioneers who once in the past, “here, where his eye fell,” found a green earth and imagined “the promised land.” After reflecting on the frailty of the pioneers’ American Dream that “their posterity might live in peace and wisdom,” he is critical of anyone ever experiencing “the fruits of the earth” because he observes “only turmoil” in industrialization and commercialization. Then, Bigness as giant remerges. Through his open office window, amidst the uproarious city, Bigness summons him to the dubious promised land if he becomes a blind slave. Resisting the temptation to surrender his life of contemplation to a life of action, he closes the window, hoping to mute the voice. Suddenly, the voice returns, but this time it carries a different message: “It is man who makes me ugly, by his worship of me. If man would let me serve him, I should be beautiful!” Bibbs’s initial rejection of Bigness allows for a rebuttal that conveys a more creative solution to the question at hand: the giant must be at the service of man, not vice versa. The definitive answer is that the contemplative life and the active life do not have to be adversaries in our journey out of the turmoil.

Instead of being a slave to Bigness like his father and serving the giant blindly, Bibbs establishes the right relationship between contemplation and action. At the core of his being, he is a contemplative in action capable of foreseeing the giant above the clouds laboring “with his hands in the clean sunshine,” creating “a noble and joyous city, unbelievably white.” In the future, the artist-businessman may become a stronger cultural force than the musician or painter in helping the blinded materialists see through the hazy smoke into the beauty of reality. No matter the outcome for Bibbs, though, Tarkington, holding firm to his job description as a critical realist, truthfully reports and criticizes the fractured relationship of contemplation and action in his industrialized and commercialized society so that we may study and improve it. He sees things as they are and not as he wishes them to be. In following his example, we can glimpse a potential path forward for the contemplative to integrate into America’s economic system of action and free enterprise without being sacrificed on the altar of Bigness. Tarkington hopes that more Americans will choose to trek that path of fruitful tension in this fragmented world, however difficult it may prove.

Image Via: Flickr