“Can We Go to the Neighbourhood?” Amber Lapp has a lovely essay on how her daughter helped her live in her neighborhood: “The sight of this toddler in a sparkly pink tutu and Paw Patrol sneakers bulldozing norms of privacy and leading me deeper into the lives of neighbours felt especially audacious because, as Americana as this town is, upon one’s first visit it can feel foreboding. The bright yellow Gadsden flag whips in the wind off front porches. My daughter cannot read yet, but if she could, some of the signs she would see include warnings about trespassing and soliciting and also, no kidding, the more abrupt: ‘Go Away.’ On what appears to be a welcome wreath reads, ‘Welcome-ish. Depends on who you are and how long you stay.’ On one porch there sits a homemade boot rack and above it a stenciled sign: ‘We don’t dial 911.’ The array of signs erects a privacy fence. Yet there is also a shirt-off-the-back magnanimity here, something that my daughter’s social persistence has unwrapped in the form of the many gifts she’s received from those who open their door to us—a porcelain doll, a polished mirror, candies, games.”

“Luddite Pedagogy: It’s OK to Ignore AI in Your Teaching.” Brad East brings the good news of luddism to the Chronicle of Higher Ed: “the sensibility behind the despairing headlines and assertive pronouncements runs much deeper than the undeniable change wrought by AI. Instead, they chart a path from a supposedly long-standing denial to final, exhausted acceptance. They do so by confessing — and sometimes commanding — a compulsory acquiescence to what we are told is self-evident reality. The machines finally won, they seem to say. The robots are the victors, and the very least the liberal arts can do is negotiate terms of surrender. I want to suggest another approach. I like to call it ‘Luddite pedagogy,’ but it’s not a retreat to purity or denial, much less “turning back” the proverbial clock. It’s a reclaiming of faculty agency, built on the refusal to accept that technology has rendered our role moot.”

“Blue Labour: Why Only Socialism can Redeem Conservatism.” Maurice Glasman recalls Roger Scruton with fondness and makes the bold argument to his British audience that “only socialism can redeem conservatism. That conservatism has been almost entirely captured by a form of revolutionary liberalism that is hostile to a stable form of life in the form of finance capitalism and has left both the Conservative Party and our country in a palsied and perilous state. That the genius of Conservatism was precisely its understanding that tradition was a condition of modernisation, that solidarity was more important than liquidity, that society requires a sense of the sacred if it is to flourish, that sacrifice was as important as choice, that the monarchy means more than the market, that meaning was more important than choice.” (Recommended by Gillis Harp.)

“Writing for the Public Good in a Democracy in Crisis.” Nadya Williams grapples with the power and limits of public writing by turning to an ancient exemplar: “What good did this writing earn for Thucydides while alive? None at all, it seems. And yet, virtue is its own reward for the one who writes with conviction. More importantly, attempting to shape the state in the virtues is a noble goal, even if it fails. It is better to try and fail than to stand by and watch the disaster unfold. To offer this education in the virtues through his writing of present events is, Thucydides seems convinced, the best public good a writer like him could bring to his state.”

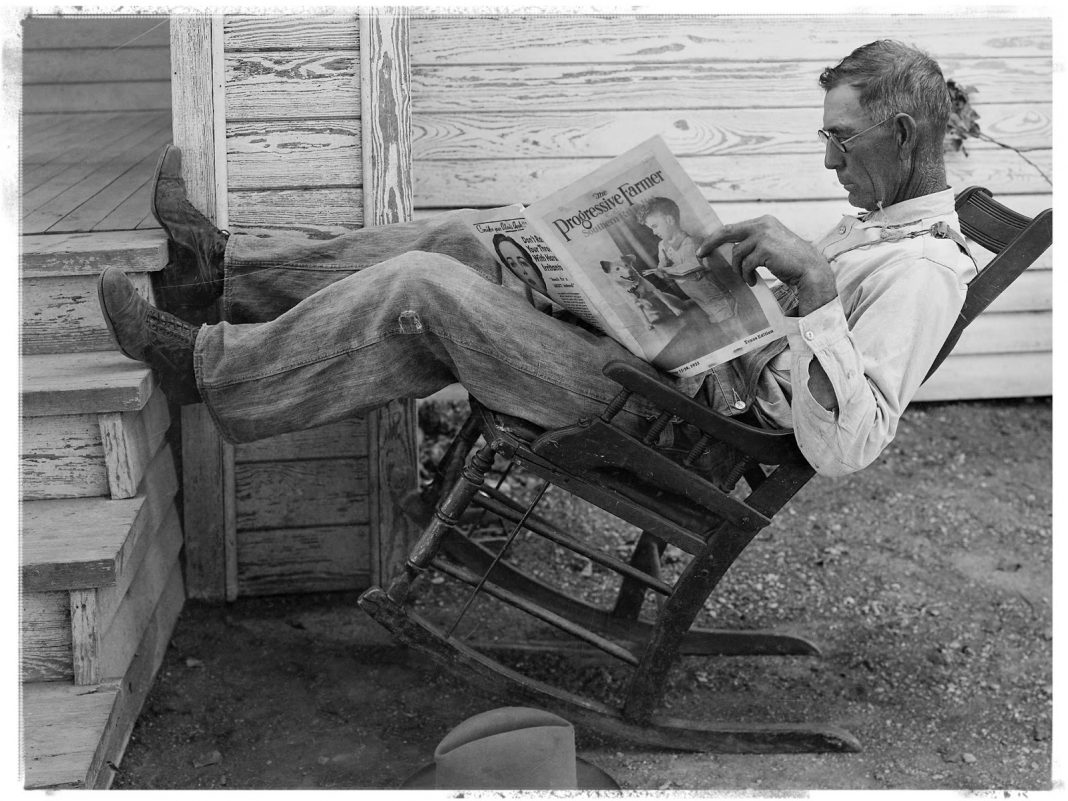

“A Small-Town Dentist Chooses to Stay.” Charlie Cotherman reflects on his father-in-law’s life and example: “We are handcrafted for communities where we are known through a multilayered tapestry of professional and personal relationships that don’t reduce us to a title, job, or skill set. For many of us, changing economic realities and expectations make it difficult to choose – or even identify – how to attain this kind of work, life, or communal interconnectivity. All the more, we should be glad for role models who show that dedication to a profession does not need to be solely determined by personal ambition, and can instead help us create and sustain these kinds of relationships.”

“Kingsnorth’s Machine.” Alan Jacobs asks sobering questions about the value of tech criticism: “I believe we keep on re-diagnosing, and describing the same diagnosis in slightly different terms, because we don’t know what to do. Some people, of course, know what to do: they opt out. And that’s why we don’t hear from them: we remain in the places that they’ve opted out of. But I continue to believe that it’s possible to use the internet healthily, without unplugging altogether. I’m trying to practice that healthy use, and do so right here where my successes and failures can be seen and learned from. In any event, we should, I think, be alarmed that our condition was properly and thoroughly diagnosed by a series of important thinkers half-a-century ago—and yet our malady has only progressed.”

“Rediscovering Pope John Paul II.” Nathan Beacom revisits the life and writings of Pope John Paul II and considers how they continue to speak to the technological, social, and moral issues of our day: “John Paul II was a man of great philosophical subtlety, which is why his scholarly writing remains impenetrable to most, but, as a public figure, he was as bracingly direct as a gust of wind. He spoke with a simplicity deeper than complexity. Before endeavoring to give moral instruction, this pope began by telling people an actual piece of good news: I know that you are afraid and anxious about many things, but you don’t need to be! You are worthy, you have dignity, and you are loved beyond all your imaginings.”

“The Inescapable Robert Moses.” Eric Kober considers the legacy of New York City’s power broker and describes the debates that continue to play out between the many different visions for this city: “The problem of making New York City a place of equal opportunity for all households continues to vex city planners and animate public debate. I worked as a city planner for 38 years in New York, starting out a dozen years after Moses’s final fall from power in 1968. I never met Moses—he died in 1981—but his shadow was ever-present. As much as New York City planners want to live in Jacobs’s world, they plan around Moses’s physical legacy.”

“Hawthorne in Rome.” John J. Miller ponders a brilliant, haunting novel: “The Marble Faun may not be the best book by the author of The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, but I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind since reading it last year. In addition to its moment of sudden violence, the tale includes perplexing mysteries, whiffs of supernaturalism, and big themes of faith, sin, and the fall of man. The Marble Faun also is unique among Hawthorne’s novels as the only one set outside his native New England — and it reveals a quintessentially American writer’s anxious encounter with an alien culture that both repulsed and attracted him.”