South Bend, IN. Back here, in the city where the St. Joseph River takes her perpetual turn for the worse, my family and I have come to pay our last respects to my wife’s mother, who passed away recently after four years of suffering from cancer. At every turn, around every corner, memories of our own lives in this place greet me — most of them causes for joy, though sometimes pain, and sometimes for ambivalence. I submit just one instance of the latter, because is demonstrates the difficulty many persons (I presume) face when they try to grapple with the dismal realities and sinister policies regarding immigration and illegal labor in this country.

South Bend, IN. Back here, in the city where the St. Joseph River takes her perpetual turn for the worse, my family and I have come to pay our last respects to my wife’s mother, who passed away recently after four years of suffering from cancer. At every turn, around every corner, memories of our own lives in this place greet me — most of them causes for joy, though sometimes pain, and sometimes for ambivalence. I submit just one instance of the latter, because is demonstrates the difficulty many persons (I presume) face when they try to grapple with the dismal realities and sinister policies regarding immigration and illegal labor in this country.

South Bend, like many depleted industrial cities amid the nation’s bread basket, has become the more or less permanent home of a multitude of migrant workers and illegal aliens from Latin America during the last decade and more. In the vast western swath of South Bend, where generations of American Poles grew up, worked, and worshipped, the factories have closed, the public and professional buildings have fallen into decline, and the Poles have assimilated and moved elsewhere. The poorest of the poor from the foreign South have tenuously settled in their place. The pews of St. Hedwig parish are all but empty these days; a few old Polish ladies keep the old hymns from falling entirely silent, and the pastor of that parish and its Irish neighbor, St. Patrick, struggles to keep alive some memory of the once coherent and flourishing immigrant community that built these churches. It was a community whose love of God kept it together, and a community whose gradual assimilation of American commercial values gradually cast it to the winds.

My wife and I moved to the edges of that part of town when we first married, settling just a block away from St. Hedwig. At the time, debate – so-called – on American immigration and labor policy appeared as if it might actually result in some kind of change after decades of destructive “neglect.” I understood well that the greatest program to redistribute wealth in our country’s history was occurring through the reallocation of manual and unskilled labor jobs to migrant and illegal workers. I understood well that it did not bode well for the legitimacy and value of law in our country when a sizable population of aliens lived in our midst in conniving and shameless spite of that law. Recognizing the need of many of these people to feed themselves and their families, I also understood that living one’s life so tenuously, with such continuous and necessitated mobility, could only result in people with neither a firm sense of the justice of laws or the reliability of a settled community.

At the time, however, one of the bills before Congress promised to make it illegal for non-state organizations to provide charitable services to illegal aliens. We were told that, should that bill pass, it would become a punishable offense for the parishes and agencies of the Catholic Church to provide food, shelter, and other necessities to such persons. Agitated by this presumption of state power, the bishop of Fort Wayne-South Bend, the Reverend D’Arcy, and Fr. Christopher Cox, a parish priest in the western, newly-Hispanic precincts of South Bend, organized a march and protest in support of their de facto flock. My wife and I, married for just over three days, joined in.

We marched in support of the foundation of charity at the root of any Christian society; we marched in declaring the liberty of the Catholic Church to feed its flock no matter where that flock might be, and no matter what its circumstances. We did not march in complacent favor of the destructive effects of illegal immigration on American society, in support of “redistributing” income from the poorest Americans to the poorest foreigners, or in scorn of the rule of law exercised within its constitutional limits.

No one would know why we marched that day, however, just to look at us. And few persons trouble themselves to recognize how the advocates of rampant, open, and unregulated immigration into this country are pleased to pit the interests of the poor against the poor. Those same advocates-ever ready to put a knife to the throat of the Catholic Church, when it proclaims its gospel of justice and charity regarding the dignity of the unborn, the importance of private property and free association, and the sovereignty of the family-were doubtless happy that day to take advantage of that Church to swell the crowds and defeat any meaningful effort to slow the economic and cultural dissolution of our country.

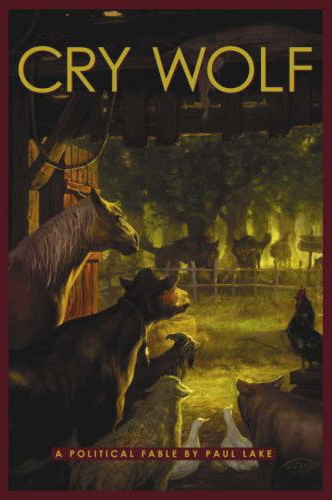

In Paul Lake’s fascinating fable, Cry Wolf, he explores some of the contradictions at the heart of our present immigration debate. He there shows in fabulous form the intrinsic fragility of all community, and the threat that domestic avarice and a contempt for the law imported from abroad pose to the traditions that make a community-local, inevitably local-viable. My review of this important, but neglected, masterpiece can be found here. My heart can be found beneath the pieta outside St. Hedwig.

While I am envious that you’re back in South Bend (Oh, how I miss Our Lady’s Unversity, and that peculiarly lovable city!), I certainly am sorry for the cause of the trip, and offer prayers and sympathy.

Thanks for this post; it’s refreshing and reassuring to see the nuanced distinction that you draw between marching for “he destructive effects of illegal immigration on American society, in support of “redistributing” income from the poorest Americans to the poorest foreigners, or in scorn of the rule of law exercised within its constitutional limits”, and marching in defense of the Holy Mother Church’s liberty contra the State.

My brother-in-law is in the border patrol. I can never read anything on this subject without feeling the absence of voices like his in this discussion. There is a curious silence surrounding the hardships of being an agent on the Mexican border.

My understanding is that the problem with the credibility of law stems largely from the hypocrisy of those who are supposed to be its representatives. They do not enforce the laws, in the interest of the profiteers. Many of the “efficiencies” of our “economy” (especially in the agricultural sector) depend precisely on allowing workers with no legal standing to work for low pay. It’s hard to fault them for accepting an invitation to disregard the law on the understanding that it’s highly unlikely to be upheld.

Mark’s point is certainly correct. We might speak of divine, natural, and human laws with Aquinas in trying to hash out the responsibility of illegal aliens, but we should also attend to the de facto and de jure laws that obtain in our country. If such aliens are de jure “illegal,” the U.S. state in its culpable and destructive capitulation to large labor-dependent capitalists has made, de facto, immigration law irrelevant.

Julana’s comment seems all the more a propos, then. The story of a border patrol agent would, I imagine, shed some light on the life of an officer of the law charged with enforcing laws many of his superiors ignore or allow to be circumvented.

As others have pointed out, the real estate crisis is in part of a symptom of these problems. All those empty, newly constructed houses in (among other places) Greenville, NC would not have been constructed so hastily and thoughtlessly had the developers had to take into consideration the wages demanded by legal American workers. The cost of honest wages might have aided in the prudential decision making of many a businessman over the last few decades; they did not, because they were undermined by a government indifferent to the enforcement of the law and the plight of its people.

What a lovely post. I linked to this. I wish more Americans and Catholics could explain our position this well. I grew so weary of explaining that our duties as citizens and as Christians, while overlapping, are not always the same(they should be, I know, but it is hard). After all, Christ didn’t say “check their green card” but rather “feed my sheep”.

The word “assimilation” keeps popping up. The illegals from the South do not “assimilate” they tend to grow their own “Barrio” and all the crime that comes with it. They do not even attempt to learn English, the language, last time I checked, of the US. Frankly, I am tired of trying to read the instructions that come with anything, only room for half of what it should be, the rest in Spanish. I am tired of my Bishop saying the illegals are more important than me and I need to give more to accommodate them. When was the last time you attended the “Mexican” Mass?

A response to the assimilation comment:

When we think about assimilation, the next question we ask ourselves is– to what? In our response, it is important to remember the history of immigration in our country and the many cultural battles we have recycled again and again. The language debate is not new– German vs English was a fight 100 years ago. The “barrio” debate is not new– the Irish and Italian enclaves of Chicago and NYC were deplored as cesspits of bad behaviour and ethnic segregation. And yet, we are today a proudly pluralistic nation that respects the languages, cultures, and history of those former immigrant groups.

So what are our immigrants assimilating into? A nation that is generous, has room for all, and has benefitted from many different national groups over time.

It is in this regard that the policies of the Catholic church are spot on. We help the poor and the marginalized because we once were ourselves. We open up our hearts to those less fortunate than us because tomorrow they will open up their hearts to us.

When we get beyond incendiary language like “illegal” and fear of our failing economy we can truly be like Christ and recognize these people for who they are– people exactly like us who moved for a better way of life out of the sheer need to feed their families.

The Catholic church has a wonderful policy on immigration that you can read about here:http://www.usccb.org/mrs/

I look forward to addressing in more detail the theme of this latest comment in an upcoming post. I find it insightful and profound in some respects, and woefully typical of the mainstream bromides that have rendered serious thinking on community, law, and identity almost impossible. However, it is worth responding here directly, if only to acknowledge the several fine comments that have been made and for which I am most grateful.

Ms. Malsbary is surely correct that the history of our country is one of immigration and assimilation; any account of political life, much less national identity, must ground itself in a comprehensive and convincing historical narrative. There are, thus, lessons to be learned from our history; as Catholics we have a particular set of lessons to learn, as suggested by George Marlin’s essay in today’s Catholic Thing (http://www.thecatholicthing.org/).

The lesson, I should like to show elsewhere, is something other than the banal equality-reduction that claims, since immigrant Catholics were once discriminated against (that is, treated as a threat to the cultural integrity of a society), we should reduce all resistance to rampant and unchecked immigration as merely “racist” or “bigoted.” Clearly Ms. Malsbary thinks that is precisely the lesson, and quite rightly directs us to a document that — in places — would make one think the Catholic hierarchy has learned nothing more than that. As she is no doubt aware, the hierarchy has a more complex understanding of “ius” (rights and responsibilities) than the thoughtless bleeding hearts to which it seems to pander let on.

But I shall, as I say, elsewhere make a case that argues against reducing either the infused virtue of Charity or the questions of communal integrity and identity to the specious and unproductive language of “rights.” To be so reductive (i.e. rejecting all arguments against illegal immigrants as “racist” and reducing ethics to the incoherent contemporary language of civil rights) is in fact the worst sort of mendacious argument: it attempts to preclude serious discussion of concrete and significant matters by shaming the observant and alarmed into silence.

It seems almost inevitable that the comment, therefore, should try to bar the word “illegal” from the discussion, when, in fact, that is the only definitive and certain adjective one can use to describe an illegal immigrant. They are not all of one race or nationality; they are not all alike in their stories of woe or flights of desparation and necessity. They are not so reducible. But they are alike in this this one attribute: justly or not, in compliance with natural law or not, they are here illegally, that is, in violation of human (positive) law.

It was part of the intention of this post to narrate (rather than argue, be it noted) two circumstances to which Ms. Malsbury refers, and of which I am sure she approves. The first was the palimpsestic stage on which this scene of South Bend immigrants plays. The second was that positive law cannot violate natural or divine law (whose voice is the Church) and still be fully and legitimately a law.

But our being, as they say, “a nation of immigrants,” does not in itself debar us from governing with our reason how and of whom that nation will be composed; and just because natural and divine law are the ground of legitimation for positive law, positive law still has a certain, independent claim upon us. I should like to understand substantially and precisely what the implications are for us of this historical fact and this metaphysical principle; we cannot hope to come to such an understanding if we blindly reduce Christian virtue to a simplistic notion of rights, much though that would benefit everyone (apparently, except the unborn); if we brand concern for communal cohesion, prosperity, or solidarity as the fixation only of racists; or if we discount (selectively, but with an unprincipled selectivity!) the nature and value of our laws.

Comments are closed.