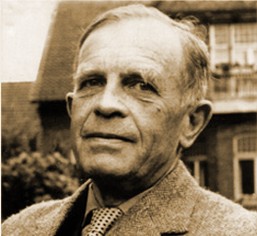

One of the few “Austrian economists” to give serious attention to familial, agrarian, and communitarian themes was Wilhelm Röpke , born in Germany yet long associated with his adopted Switzerland. He saw family life as “natural and free,” with the “well ordered house” serving as the very foundation of civilization. He labeled a healthy peasantry “the very cornerstone of every healthy social structure,” adding that a “peasant who is unburdened by debt and has an adequate holding is the freest and most independent man among us.”

One of the few “Austrian economists” to give serious attention to familial, agrarian, and communitarian themes was Wilhelm Röpke , born in Germany yet long associated with his adopted Switzerland. He saw family life as “natural and free,” with the “well ordered house” serving as the very foundation of civilization. He labeled a healthy peasantry “the very cornerstone of every healthy social structure,” adding that a “peasant who is unburdened by debt and has an adequate holding is the freest and most independent man among us.”

The Spring 2009 issue of The Intercollegiate Review carries my essay, “Wilhelm Röpke’s Conundrums Over the Natural Family.” One passage explains his celebration of the Swiss village as the “ideal” form of human existence, a model to be emulated:

“In finding answers, Röpke was—and is—correct in trying to rehabilitate social life by returning human beings to decentralized, autonomous, self-sufficient, functional homes, where education and work would be integrated into the daily flow of family living. Toward this end, he correctly saw mid-twentieth-century Switzerland to be a model state. ‘As the common enterprise of freedom-loving peasants and burghers,’ he wrote, ‘ it has offered the world a living example of the harmonious integration of [rural] and city culture.’ He described a real village of about three thousand people with nearby farmsteads in the Bern Mittelrand, a place that combined artisans’ shops, small factories, a brewery, a dairy for cheese, a ‘highly tasteful’ book store, and ‘a great collection of obviously thriving crafts and craftsmen.’ He added ‘that the whole place is remarkable for its cleanliness and sense of beauty; its inhabitants dwell in houses which anyone might envy; each garden is lovingly and expertly tended; [and] antiquity is protected…. This village is our ideal translated into a highly concrete reality.'”

The full article can be accessed here.

–Allan Carlson

Winnebago County, Illinois

How about we promote the “Front Porch” school of economics?

Thanks for the article and post. May the Roepke Revolution begin!

Marty,

Economics means, from the Greek, “household management.” I think nearly everything that is written here is essentially a contribution toward “the Front Porch School of Economics,” which begins with the local and the particular, not the abstract and universal (e.g., “utility maximizing rational choosers”) that is the norm for modern economic theory. So, I think – and hope – we’re doing exactly that!

Apropos a lecture I delivered on the Anti-federaists yesterday at Notre Dame, and tomorrow at Christendom College, it’s worth pointing out that they frequently pointed to Switzerland as the model that America emulate – a decentralized, agricultural confederation of States, themselves composed of decentralized localities. Geography may have made this difficult, but it was our greed that made it impossible. But for some different decisions early in our history, Roepke might have pointed as well to America as a model of sensible oikos-nomoi.

I agree. This site as a whole is doing a great job promoting the front porch school.

How very interesting! A localist who defended international free trade. I have to wonder if he would have felt the same way in today’s world, where nearly product in America that can be imported, is imported.

Also, I find this interesting (from the cited article):

“There must ‘naturally be room,’ he said, for public old-age pensions, health and accident insurance, widow’s benefits, and unemployment relief in a ‘sound . . . system in a free society.’

I have to wonder, how many Front Porchers would agree that there should be room for publicly funded health insurance? Is it better to keep healthcare in the hands of corporations (giving us the slap-dash, unequal mire we have today), or do we turn over the industry to the arbitration and funding of a governmental system? Here’s one more place where the rubber meets the road. How best do we apply distributist principles to this area of current national politics?

Rimshot,

I have to wonder, how many Front Porchers would agree that there should be room for publicly funded health insurance?

As an Obama voter, I likely am a pretty significant outlier amongst all Front Porch contributors. That being said, count me down as one devotee of populism and localism who believes that strong–often, as Röpke himself put it, “compulsory”–collective programs and institutions must be in place if organic communities and neighborhoods are to develop. To my mind, that certainly means publicly-funded (probably single-payer, but I’m not wedded to that) heath insurance, extensive protections and encouragements to labor unions and local markets, zoning regulations to prevent sprawl and to protect parks and bike paths and other common public spaces, and other similar acts. I see it all as necessary to creating–or maintaining–an environmental within which local distributist practices would be able to take hold.

I’ve always found an underlying tension in Roepke between his distributism and his Austrianism. The Humane Economy is almost poignant in its inability to resolve these tensions. The Austrians tend to be indifferent to scale, and their is nothing in the theory that can justify limited the size and scale of ownership and enterprise. But without such limitations, the theory doubles back on itself in practice. For as firms grow, the grow more powerful, and it is natural for them to arrange the state to their own purposes, purposes which are usually anti-competitive. For the growth of government is not so much a result of socialism as of capitalism, as Belloc pointed out. The capitalist wants, above all, security of capital, and pure competition is the greatest threat to this. No one, not even the Marxist, fears pure competition as much as does the pure capitalist.

Rimshot, as for a “distributist” health care system, see http://distributism.blogspot.com/2007/07/sicko-phancy.html and

http://distributism.blogspot.com/2008/12/health-care-system-and-guilds.html

Patrick,

Geography may have made this difficult, but it was our greed that made it impossible.

I’m sorry, but I think I have to disagree with this, as I find it misleadingly (though certainly not intentionally so) simplistic. There are all sorts of historically contingent reasons–having to do with religion, with the mostly English forms of government instituted in the colonies, with the language and mores of the people who settled here, etc.–that made an Anti-Federalist/Swiss canton system improbable in the U.S. besides just geography, and there are all sorts of “basic human nature”-type reasons besides just greed that led to the creation of a national union that was more–to borrow Sheldon Wolin’s terms–“intending” (intentional, rational, aspirational) than “tending” (conservative, sentimental, personal). But perhaps what I’m expressing here is just a disagreement with your very thoughtful and challenging defense of the Anti-Federalists, a disagreement that I may have to write out more fully.

Thanks for reminding this pagan that he needs to read some Ropke. Now Medaille, I catch your drift but I suppose Stalin’s purges of everyone from the Constructivists to intellectuals and every other element he either could not control or disliked was a non-competitive act?

I know, I know, we can discuss how Marxist he was for days.

That Ropke’s implied conflicts between Distributionism and Austrianism were poignant is a good thing. These choices should be both scientific and emotional. The Brain has lobes and both interactive and independent neurons for a good reason. Descartes’ all-knowing Decider Pilot , the Homunculus is a rather incomplete expression of free will. The fact that a Federal Homunculus is now ascendent and the Separation of Powers diminished is one of the best illustrations I can think of that we are at peril when we refuse to acknowledge the beautiful linkage between our lapsed form of government and the human brain.

The insular and homogeneous Swiss Cantons and their Republic of Mountain Redoubt might be easier to pull off in his model of “common enterprise” but I wonder if this mutt America could pull off an entirely more dirty, confounding and yet invigorating “uncommon enterprise”. Federalism used to include and respect “States Rights” until our reservations about a Standing Army were thrown out with the perfidious notion of slavery. When your Chamber of commerce relies upon depleted uranium arms, you know “common enterprise” is beside the point .

Since Wendell Berry got me interested during my undergrad in the kind of decentralized local economies I have been scouring local libraries for works by Allan Carlson, Herbert Agar, Wes Jackson, Roepke, The Southern Agrarians, Norman Wirzba, David Orr and others. I am delighted beyond words to have found FPR as I am now beginning work on my master’s degree and plan to focus on American Agrarian Literature. It will be an indispensible source of information and conversation.

As for Roepke, it is too bad, as Patrick Deneen noted, that early developments in American history have made his kind of economic structure so unlikely for our future. The most prominent anti-federalist, Thomas Jefferson, wrote in a letter that “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independant, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to it’s liberty and interests by the most lasting bands.”

Similarly, as Allan Carlson quotes in The New Agrarian Mind, John Adams said that the ideal economy meant “‘an interdependent community,’ of farmers and modest merchants, with government maintaining the balance. All the founders held that ‘a wide diffusion of property…made for enterprise, family responsibility, and in general for institutions that fit man’s nature and that give a chance for a desirable life.'”

It is late for America to follow this original path, but hopefully not too late. That is the hope and the promise of the people on this site. Thank You!

Just curious: what happens when the number of farmers grows too large to be supported on the amount of farmland?

Mr. Sabin, I cannot even begin to understand your how your remarks on Stalin relate to the discussion. What am I missing?

W of M, In that case, the farmers use their land, their tools, and their skills to enter other businesses. You can do that easily when you have land, skills, and tools of your own. In fact, it is precisely the distributed ownership that makes such systems agile, in a way M-Form mega-corporations are not. That is why most innovation is from small firms.

One point, however. Agrarianism is not really about making everybody a farmer, imo; it is about re-establishing the proper relationship between town and country. Agrarianism does not do away with the city, not even the great city. But whereas corporate urbanism tends to diplace the farm in favor of the agri-business, agrarianism allows both town and country to flourish.

Mr. Medaille,

I was boring in on your comment that Capitalists fundamentally fear competition more than Marxists.

As in :”No one, not even the Marxist, fears pure competition as much as the pure capitalist. “. I cannot quite understand how the Marxist State which collectivizes to avoid free competition would fear competition less than Capitalist systems…..unless of course, the ruthless abolishment of competition renders fear of it moot.

Stalin, of course, made a career out of vigorously stamping out all perceived competition whether real or not.

In furtherance to Medaille’s and W/M comments, agrarianism is also an invigorated forum of multi-tasking. People in this modern era talk proudly about their ability to multi-task amongst their various technological gadgets within the so-called service industries but real multi-tasking reached a greater expression during agrarian ages when a farmer might have been a legislator or lawyer or artist or surveyor while he farmed and the farmers wife was a paragon of multi-tasking….spinning, rolling cigars, feeding, teaching etc etc etc. while assisting in all the farming tasks . Medaille is right that the Urban rural axis was far more intertwined if more distinct in its physical transition than it is now. Agrarianism also imposed a greater check upon Standing Armies than our current consumer society does. Absenteeism and insurrection in response to seasonal harvest demands chastened the leadership constantly.

Rimshot:

The “free” in “free trade,” in Richard Stallman’s terms, should be read as in “free speech.” That is, it’s the freedom to enter the market without market entry barriers and costs imposed by the state.

Unfortunately, what the neoliberals and globalists call “free trade” is analogous to Stallman’s “free beer”: the costs of the activity are actually subsidized by the state so that privileged corporate interests can engage in them at less than their actual cost.

And just as you drink a lot more beer when it’s free, you engage in a lot more global trade when all the costs are externalized on the taxpayer and you’re protected from competition by more efficient local producers.

Mr. Carson,

I always loved that term “external costs”….the less than salubrious placed off in an accumulating pile like they do not exist or with some expectation that the “Me Make Bad” Fairy is going to come along, twinkle it with a wand and make it all go away. Accordingly, nobody ever makes the moves to limit said “externalities” or incorporate them in actual costs of overhead.

Its the corporation that centralized the economy. The government should have never sanctioned corporations. In this way, capital was preferred by the government over land and labor in the means of production. The Bible gives us a familial economy, where each family owned land. Those who worked, were those who ate.

Comments are closed.