Note: This post is taken from a book in progress, The Paradox of Freedom: The Making of Modern America, coauthored with Peter Field.

—

Conservatives have reason to fear populism. In most nations, populism is destructive, irrational, and tending toward centralized power. But this has not been true in the United States where diverse populist impulses have worked in the direction of conservation, of protection, of preventing or reversing certain kinds of change. In the nation’s first century, a deeply held fear of government tyranny meant that populist sentiments usually arose in a fashion to check power rather than to usurp it. Even in the late 19th century, when self-proclaimed populists found the greatest threat to their economic and cultural inheritance coming from corporations rather than government, populism didn’t produce a Committee of Public Safety. Americans have historical reasons to not fear populism.

A new form of populism emerged in the 1970s and contributed mightily to the direction of our nation ever since. Politically, this new populist sentiment forced realignment in the two parties. Deeper than party alignment, however, was a cultural shift back to a mistrust of government power and a new, often strange, but undeniably powerful, vision of American history and purpose. Today we can feel the cultural rumblings primarily in politics, but the new populism was early evidenced in cultural forms. Today we can easily forget how dark things looked in the 1970s and how much people feared that they might be living in the sunset years of our nation and its characteristic way of life. We forget how important patriotism and a belief in the goodness of the nation were to the health of the republic.

Consider the year 1976, which marked the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence and the American Founding. This patriotic celebration came during a crisis in confidence and a crisis in national identity. A government-sponsored national celebration of the country’s founding would remind Americans, organizers hoped, of the defining principles of the United States, especially the emphasis upon liberty and equality. On commercial television, in classrooms, and in numerous other venues, the nation was learning about its past and its founding principles. Yet this celebration of the nation’s history did not generate the kind of patriotism or interest that one might expect from such an anniversary. Americans had become unsure of themselves as a nation. In a very brief span, the nation had gone from unprecedented prosperity and economic power to a very real sense of economic limits. Still a military superpower, the United States seemed like a confused giant by the mid 1970s. After establishing the most sweeping civil rights legislation since the Reconstruction era, the country witnessed widespread racial violence and deep disillusionment among many black Americans along with frustration and resentment among many white Americans. In the wake of Watergate, the collapse of South Vietnam, the end of long post WWII economic boom, the celebrations of America’s 200th year seemed a struggle to muster the appropriate patriotism.

Still, the year-long education about the American founding served to help many people think afresh about the values and ideals that made the nation unique and worthy of respect and support. Amid the frustration, the cynicism, there were also signs that many citizens wanted to think about the idea of America: about the ideals (rather than simply the reality) that gave shape to a distinctive national identity. As in all periods of American history, the charmed words of the American sense of self were invoked: freedom, rights, equality. However, the meanings of these elusive words were very much up for grabs, even in the bicentennial year. Perhaps the most important struggle for the nation in the years that followed was how these shared words would be defined.

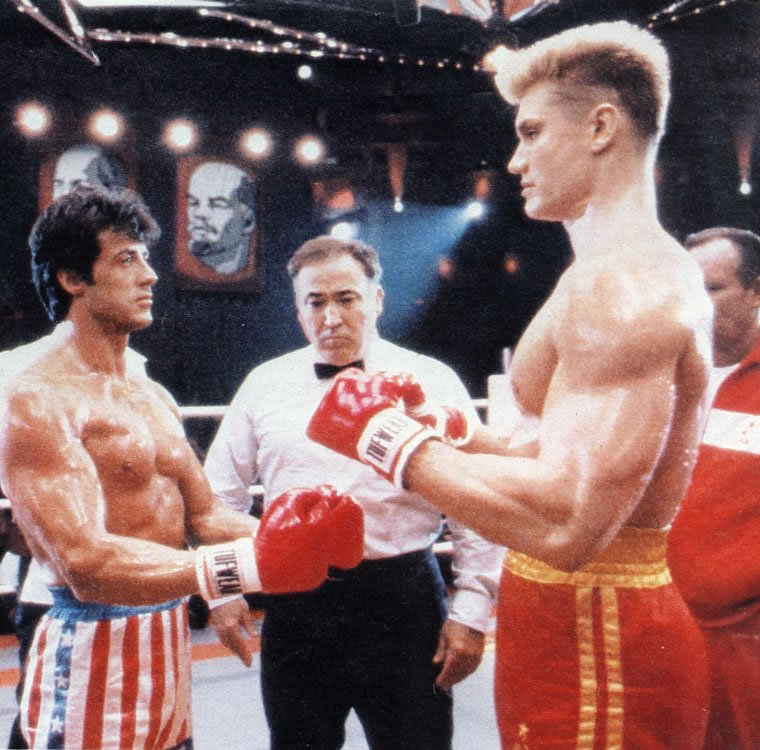

In the same year that Americans were reflecting on the words of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and a host of lesser known figures from the Revolution, they were also casting about for more contemporary images and symbols of America’s distinctive purpose and identity. Perhaps no cultural expression better captured this inchoate sentiment than the unexpected success of the movie Rocky. This story of a struggling boxer in a decaying Philadelphia neighborhood presents an unsavory look at contemporary life in America. Rocky Balboa (ring name of “The Italian Stallion”) is a good natured, shy, and intellectually limited boxer who struggles to make ends meet in a depressed ethnic, blue-collar community. All around him are the signs of economic problems and a decaying social order, as Rocky walks down dirty streets populated with aimless youth. The tight-knit community is falling apart with increasing joblessness and crime–even Rocky must depend upon organized crime to help him survive.

By a twist of fate Rocky has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to fight for the title against the apparently undefeatable Apollo Creed (who was meant to remind the viewers of the great boxer Muhammed Ali), an image savvy, self-centered, and cynical black boxer. Told from the point of view of white, blue-collar ethnic Americans, the story exposed the frustrations with an America where patriotism had become passe, where hard working people with traditional values seemed to be left behind. In such depressing times Rocky represented an older America (one that many people thought was already gone) where hard work, decent living, and patriotism were widely practiced and approved.

While Creed had all of the advantages of the best trainers and the best equipment, Rocky worked out with primitive and makeshift equipment. The Italian Stallion, who represented the un-touted, obscure, hard working American, made no excuses—he only saw opportunity. While Rocky did not win the match, he made a very good show of himself, knocking down the champion several times and going the distance in a brutal match. For him and for his audience this was a major victory that reaffirmed all of the old values of loyalty, hard work, and individual initiative. It was a victory of the little guy against the established powers—yet unlike other movies that attacked the establishment this one affirmed a love of country and a set of values that many people associate with America.

Rocky became the big success story of 1976, winning at the box office and at the Academy Awards. Audiences could identify with the film as it at once gave expression to the frustrations and the ideals of many Americans—it pointed to what had gone wrong with the nation even as it pointed toward the ideals Americans invested in their nation. In 1976 many people yearned for a renewed sense of pride in the United States even as they had come to distrust their government and the many elites who, they believed, had brought it to ruin. In the coming years many Americans looked for leaders who understood their point of view, who could take America out of the hands of various elites, and who could project an image of a strong and prosperous America. This new populism made possible a political realignment that sundered the New Deal coalition that had dominated American politics since 1936.

For those of us who remember that time, the generations that grew up in the 80s & 90s strikes many of us as soft, self-indulgent, and silly. (Obviously there are many exceptions — my oldest son being one.) We were silly in our own ways too — but the world seemed darker then with the Soviet Union looming over us (a global power with the real potential to deliver a lethal blow — unlike the cave dwellers in Afghanistan). In one sense things feel eerily similar now — a real sense of our limitations has returned. But isn’t this a good thing? In some ways the 80s and 90s seem to me to have been the purchase of of few more years against the inevitable. Can American populism embrace limits and situate itself within a truly conservative outlook?

“In the same year that Americans were reflecting on the words of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and a host of lesser known figures from the Revolution, they were also casting about for more contemporary images and symbols of America’s distinctive purpose and identity. Perhaps no cultural expression better captured this inchoate sentiment than” The Gap” blue jean stores.

Rocky may be feel good, but the real expression of from where, to where is The Gap.

Populism is a knife. It cuts, either to harm or to heal. Mostly harm, from what I can tell. The “ordinary man” on which most populism rides, is itself a fiction. There is no such ordinary man.

I’m surprised that you’d say dangerous populism isn’t as old as the Republic. After all, one of our first conversations was concerning the Jacksonian wing of the “Right” in America. And specifically how I had learned the virtues of Hamilton over Jackson. It is obvious that populism leads almost necessarily to tyrants installed by the mob to do their “good work”. I’ll take the evils of oligarchies, thank you very much.

Heck, wasn’t even the Whiskey Rebellion a failed populist movement?

David,

Populism in the US, rather than populism as such, comes from some combination of the habits of self-rule and a threat to self-rule. These populists expressions (with a few exceptions) are not trying to create or tear down, but are about preservation or recapturing. Whether this will be true after a longer tutelage in distant government and radical individualism, I cannot say. Habits die over time.

I am a better student of historians than history, I’m afraid.

But I share your unwillingness (which might be better described as systematic doubts, yes?) to guess what these recent waves of anti-cultural propaganda have wrought. There are plenty of people who were happy to live under Empire (either that of Persia, Rome, England or America). They were “popular” empires. I wonder, what role does populism play in the life cycle of Empires? Perhaps this is a question above my pay grade.

I can only say that they are not my cup of tea.

Ted,

Was your co-author for this work Peter S. Field of the University of Canterbury (NZ)? I only ask because I had the pleasure of taking two history courses that Prof. Field taught while he was a visiting professor at the City College of New York in 2005-06.

A nice piece! There were other terrific “reactionary” films in that era: the inaugural STAR WARS…EPISODE IV (the “good” Republic versus the “evil” Empire); the original DIRTY HARRY (take that bleeding heart San Francisco liberals!); and (a little earlier) THE OUTLAW JOSIE WALES (a Distributist classic…with a peculiar Confederate twist… on the building of community). Who would have guessed that the Hollywood of that decade might be capable of creative reconstruction!

…..a populism that “that sundered the New Deal coalition”…..come now. The New Deal, anvil hammered into the sturdy war chariot of a Raw Deal under our current slap happy generation of faux conservatives has done nothing of the sort. The Glory of the State is bandied about across the board while the paranoideproletariet are maintained in a pitched state of pathos over spooks in every direction. We are told to expect less of everything but government. I’ve seen a better class of golf course pond leeches than the majority of our current crop of faux conservatives.

One should remain confident that the current brainless trust of the “Conservative” wing of american Politics will follow up the “Freedom of Choice in Lightbulbs Act” with a “Depends with sprightly stars and stripes motif for every Incontinent Citizen Act”.

“Conservatives”. Yea……. right. At least the perversions are ecumenical, the Liberals being kept in line by an edifice of Political Correctness.

This is what happens when falsehood pays, you get brigandage as a national pastime. You also get politicians who claim conservative bonafides yet are as cloyingly perfumed as the most effete of oriental despots. You also get liberals who think a Security State is a fine idea. In other words, the Pledge of allegiance shall forthwith be re-directed from a hand over heart posture to bending and grabbing your ankles for a new verse of “Brace Yerself Brenda”.

Found this through Tenured and other’s links. So how does white racial resentment play into the universalized narrative of “Americans” and what is your take on Jacobson’s sharp points in Roots Too on the film and the importance of white ethnic backlash?

An interesting post. I am sure you take on those obvious problematics in the book, but was curious as to your take.

Unsavory? Maybe, maybe not. What I witnessed was an accurate blue collar 1970’s Philadelphia Americana no different than Jackie Gleason in the Honeymooners. Underdog, hardworking, patriotic, dreaming, catholic Italian, bare minimum living Heros of our not so distant historic past. Italian Americans literally exited movie theaters thinking they were indestructible. Haha. Great time to be a patriot.

Comments are closed.