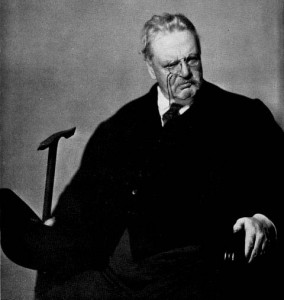

I recently received a handsome, newly published copy of the book America Through European Eyes, published by Penn State University Press and edited by Jeffrey Isaac and Aurelian Craiutu. Chesterton built (if intellectually) a sizeable portion of this Front Porch, so it’s fitting to allow him some time to ruminate with a cigar and a glass of scotch. Here’s a portion of what I wrote for a chapter in that book, namely an exploration of Chesterton’s thoughts on patriotism and cosmopolitanism.

________________________________________________________________

G.K. Chesterton took issue the notion that there was really such a thing as “humanity” from a human eye’s view. Humanitarians claimed to love humanity while in fact evincing disgust, condescension and disdain toward most ordinary human beings. “A strange coldness and unreality hangs about their love for men. If you ask them whether they love humanity they will say, doubtless sincerely, that they do. But if you ask them touching on any of the classes that go to make up humanity, you will find that they hate them all. They hate kings, they hate priests, they hate soldiers, they hate sailors. They distrust men of science, they denounce the middle classes, they despair of working men, but they adore humanity” (The Patriotic Idea[PI], 596). Cosmopolitanism was, for him, “a psychological impossibility”: cosmopolitanism was a belief in “unreality,” against the “reality” of nations and the actual bonds that animated humans (PI, 603, 605, 607). Chesterton did not deny that humans longed for the infinite and the transcendent; he found that longing among the most praiseworthy of human desires and aspirations. But, he believed such longing to be improperly directed to the political sphere; rather, he maintained that such longing reflected, at base, the aspiration to know the divine. Humans seeking the God’s eye view of humanity assumed a stature and insight that was unavailable to them; rather, if there was the possibility of “seeing” to the universal, it was only through the particular: “real universality is to be reached … by convincing ourselves that we are in the best possible relation with our immediate surroundings. The man who loves his own children is much more universal, is much more fully in the general order, than the man who dandles the hippopotamus or puts the young crocodile in a perambulator…. A man who loves humanity and ignores patriotism is ignoring humanity” (PI, 597).

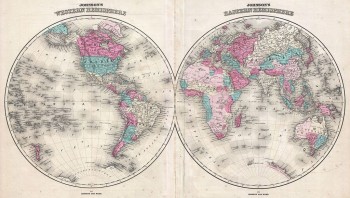

The human world is one of particularity, concrete affections and limits: choices must be made between particulars, to the exclusion of others. Cosmopolitanism – another word for imperialism, in Chesterton’s view – harbors the illusion that no choices must be made. To be everywhere and to love everyone is to be nowhere and love no-one: “If you go to Rome, you sacrifice a rich suggestive life in Wimbledon…. The moment you step into a world of facts, you step into a world of limits” (Orthodoxy [O], 45). Cosmopolitans cling to the belief that life in the world can be configured without preliminary commitments, limiting parochialism, or unchosen loyalties. “The assumption of it is that a man criticizes this world as if he were house-hunting, as if he were being shown over a new suite of apartments…. But no man is in that position. A man belongs to this world before he begins to ask if it is nice to belong in it. He has fought for the flag, and often won heroic victories for the flag long before he has ever enlisted. To put shortly what seems to be the essential matter, he has a loyalty long before he has an admiration” (O, 71-2). Cosmopolitans evinced a preliminary dislike for the world, its reality, its messiness and incompleteness. Those working for the “unreality” of the World State exhibited a form of modern Gnosticism with its hatred of the created Universe and its aspiration for an alternative reality when the present world might pass away. The difference was that modern Gnostics like Wells and Shaw saw the new Kingdom unfolding politically on Earth through the transformative efforts of humans alone.

At the same time, Chesterton did not argue for the inherent perfection of all that was “given” and on behalf of an accompanying sense of complacency: while not a pessimist, nor was he a Candide-like optimist who believed that we lived in the best of all possible worlds (O, 71). For instance, he was the first to recognize the limits and drawbacks of the human reality of parochialism. Yet, against the “unreality” of cosmopolitanism, and particularly the fervency with which it was pursued in the modern age, he endorsed localism, patriotism, and nationalism in the face of what he regarded as the deeper dangers and even evils emanating from abstract universalism:

“The danger of small communities is narrowness, but their advantage is reality. Now, at any specific stage in the world’s history we ought to ask ourselves whether humanity is in greater danger from the narrow arrogance of small people, or from the phantasmal delusions of empires. That is the question which confronts the European of to-day, and the answer is not very difficult. It is idle to tell him that nationalism is sometimes an evil in the confusion of a heptarchy, when the fact that stares him in the face that the modern evils arise from remoteness, from unreality, from the circulation of wealth far from its producers, from the waging of wars far from the seat of action, from the wild use of statistics, from the crude use of names, from the investor and the theorist, and the absentee landlord.”

[PI, 614]

More dangerous than the “narrow arrogance of small people” – which he acknowledged to be a danger – were the efforts to dissipate or extirpate local forms of life in the name of abstract principles or love of humanity (PI, 614). Chesterton believed that such efforts would ultimately undermine whatever benefits might be secured by overcoming parochialism, since whatever vitality and devotion larger cosmopolitan entities might achieve had their source in preliminary loyalties. It was the blindness of cosmopolitans to that source – their ignorance that within the very word “cosmopolitan” was the root word polites, meaning “citizen” – that doomed not only their own project, but threatened to extinguish the “reality” upon which human relations are based.

Chesterton believed that one could not rest content with the imperfect conditions of “reality,” but that, before reform should be undertaken, a preliminary “cosmic oath of allegiance” has to be declared (O, 77). Chesterton’s Christianity and his eventual conversion to Roman Catholicism, were based on his understanding of the fundamental alienation of humanity from existence, the fact that “we do not fit in this world” (O, 85). Yet, the world is our reality – along with the limits that accompany reality – and that, opposed to the transformational reforming instincts of moderns to make the world anew, Chesterton asserted that first this impulse must be chastened by an appreciation for, and even love of, that created reality. In short, he argued, we “need to hate the world enough to change it, but love it enough to think it worth changing” (O, 77). “Acceptance” of reality therefore precedes the impulse to transformation: “this need for a first loyalty to things, and then for a ruinous reform of things” (O, 79). Christianity, so understood by Chesterton, does not seek to remake the world uniformly in the image of human desire for order, but accepts diversity and disorder as part of a larger overarching plan. Christianity (as, before him, Tocqueville also expressed) resists pantheism and “accepts” the manyness of “reality” as the only means and avenue by which we can contemplate the universal order that lies behind it: in contrast to pantheism,

“Christianity is on the side of humanity and liberty and love. Love desires personality; therefore love desires division. It is the instinct of Christianity to be glad that God has broken the universe into little pieces, because they are living pieces. It is her instinct to say ‘little children love each other’ rather than to tell one large person to love himself…. All modern philosophies are chains which connect and fetter; Christianity is a sword that separates and frees.”

[O, 139]

It is this theological understanding of humankind, of the “reality” of human diversity, of the temptation to the “unreality” of modern dogmas of the brotherhood of all humankind, that underlie Chesterton’s often conflicted analysis of the United States in What I Saw in America. On the one hand, he saw a nation state, one firmly inspired by patriotism and particularity; on the other hand, he observed a creedal nation that might have tendencies toward the “unreality” of cosmopolitanism. The strength of the latter as it existed in America was, in his view, based upon a firm devotion to the former. Much like Tocqueville, he viewed America as pointing the way toward “the future of democracy,” but he saw that future clouded by the challenge that modern democracy’s tendencies toward political pantheism and international cosmopolitanism posed to itself: “democracy is a very serious problem for democrats” (WA, 254). In Chesterton’s eyes, democracy and Christianity shared similar worldviews, and with the rise of religious doubt, he believed, one could expect to see a concomitant rise in doubts about the prospects of local self-governance, and instead increasing reliance upon experts and elites, in bureaucratic structures, in a growing divide between the rich and poor and the triumph of abstraction over “reality” (WA, 257-263). What Chesterton “saw in America” was a possible future that caused him enough anxiety to write with hope that it would not come to pass. His fears come out in the many passages in which he expresses his confidence in the avoidance of that future, but there are times when he appears to be doing nothing else than laughing in the gathering dusk.

[…] View original post here […]

“The danger of small communities is narrowness, but their advantage is reality. Now, at any specific stage in the world’s history we ought to ask ourselves whether humanity is in greater danger from the narrow arrogance of small people, or from the phantasmal delusions of empires.”

The bane of localists is the “Luddite” label, as if by affirming the value of living simply and sustainably within one’s means and in the community one loves is somehow jettisoning oneself from the collective boat of human achievement. This quote succintly states the truth of the matter, that although some people may be justified in characterizing certain populations as philistines and Luddites, erring on the side of caution would impel one to prefer this fate to the abuses of modernity’s destructive corporate dictators.

Another fantastic article. FPR keeps me from getting caught up in the gathering dusk and gives me hope that Chesterton’s fears, though they have come true, are not dead.

Another fine essay…..Chesterton’s quotes regarding the choice between “narrow localists” and the “phantasmal delusions of empire” with its “circulation of wealth far from its producers” …and the “waging of wars far from the seat of action” and “wild use of statistics”……..wow but is this not a comprehensive description of our current crop of world-improving multi-cultural cosmopolites? Isn’t the choice actually a straw man? Are we not able to consider past, present….local and global simultaneously and reach an informed and equitable conclusion? It is odd that after that trite little advice to “think globally and act locally” , we have a system that thinks and acts globally against the interests of the local. The current Warcrat Cosmopolitans would like us to believe that they are furthering a great agenda of liberty so that all the people will be released to productive self-determination within a packaged construct of disingenuously named “democratic free trade”. Antagonists either erupt out of the spoiled firmament of this flawed construct or they are created as the circumstances may demand. Meanwhile, the people of the world are reduced to the role of that of victim where their supposed cosmopolitan urges shall finally be sated only in the multinational graveyard maintained by the government contractor of record.

We run great circuits around the planet, 24 hours a day, seven days a week and yet we cannot arrive at a scalable system productive for all…one that forms a strong structure because the foundation is strong…..one that reflects the discursive potential of our brain and it’s physical-social manifestation in the form of our as yet depauperate Discursive American Political System. All this information and we willfully dismiss it because we feel that statistics create knowledge rather than simply act as a gauge determining whether knowledge merits the honorarium of “wisdom”.

Google Dab Kili or Khojal Waziristan in Pakistan and you will be brought right into the courtyards of these agricultural hamlets and you will see the diverse language of agrariansim laid out clearly with farm fields, waterworks and habitation speaking volumes of a long history of life. And yet, we are being asked to believe that these people detest us for our freedoms. We are being asked to swallow a ruse that they hate us because we are not them and that their ancient muslim law of hospitality will never be extended to us until they adopt our ways or we adopt theirs. We are being asked to ignore the fact that the war we fight was not sponsored by these farmer citizens of Waziristan but by modern men of a global wealth class…… on both sides……. that have decided to prosecute a zero-sum War of Wills clad in a dense fabric of lies. We are in the final chapter of the Afghanistan phase of the Cold War and everywhere, local life, local farming and the wisdom and timeless strength of agrarianism is being derided as either insurgent or backward because it wishes to protect its own life and dignity.

Subversion and Hostile expressions of power are the forces that govern our lives now. That those who might like to reinvigorate localism are characterized as insurgents within their own home by a so called Representative Government that habitually sidesteps or perverts the Representative System is an indication that a great hoax is at work. A process has been put in motion where the global systems and the techno-utopian project of civilization within the modern era is put at risk because the individual whose freedoms are the rationale for the States Actions must be co-opted , subverted and perverted in order that those freedoms are “preserved” by the State. In effect, it is a groaning edifice of high-tech negation , a great an endless souk of false choices. This is the greatest and deadliest Bait and Switch in History.

When we abandon our safe yet bitter sinecure as spectator and recover both rights and RESPONSIBILITIES as citizens, the ongoing act of mass negation may be reversed. We do not have the luxury of simply withdrawing from a larger world but the State has successfully pulled off the charade that it has the ability and impunity to expel us from the wisdom and infinitely regenerative capacity of our own local life. At the very least, it has created a tax-subsidized distraction from the local scene.

Think and act locally and the globe becomes local too. Not the homogenized and deracinated negation which the Technological Deity would have us admire but a local that is humanity’s greatest expression of simultaneously modern and traditional thinking: a respect and reverence for life. This is the timeless gift we continue to rebuke because we think we have something better to do.

“More dangerous than the ‘narrow arrogance of small people’ – which he acknowledged to be a danger – were the efforts to dissipate or extirpate local forms of life in the name of abstract principles or love of humanity (PI, 614).”

I may be missing the point, but does engendering a love of humanity require us to extirpate local forms of life? Perhaps some forms of cosmopolitanism do entail the destruction of local ties, but is this a necessary relationship?

Maybe a love of humanity does not have to dissipate local forms of life, but it can help counter the dangers of, not a “narrow arrogance” or Ludditism (if that is a word), but the often real psychological tendency of local or national affections to reinforce the dehumanization of any that do not belong.

Is it impossible to conceive of a form of life that values local attachments and affections while at the same time loving, on at least some level, all of humanity? Can there be a Christianity that is deeply committed but that also sincerely accepts other faiths and beliefs, or more importantly, lack of belief? I want these to be possible, but the strain of Christianity that I experienced (and practiced) for many years, while guided by love, could not really reach this level of acceptance.

As I said, I may have missed the point. If so, please forgive my error.

P.S. I was at a nice dinner last Thursday with someone I think you know, Ruth Abbey.

It’s interesting that you bring up Christianity, Michael, because one could argue that it is that religion–with its universal admonitions, transcendent commands, and world-wide claims–which more than any other complicates the conservative project. Obviously many, many believers would insist–as I would–that a properly conceived understanding of the Christian call to love your neighbor need not and does not sunder the neighborhood; on the contrary, it may simply add layers to human existence, allowing us to see ourselves has have particular, local relationships and obligations to our families and neighbors, but also a humane connection all others, in their families and neighborhoods as well. But of course, negotiating the overlaps between those varying sets of commitments–when does is time, money, attention, preference, better delivered to the local, and when to the global (not to mention all the national or federal steps in between)?–is difficult, and probably always will be. In the end, Christianity is at least in part an interventionary and disruptive religion–Christ came to offer a sword, after all–and thus always complicates the maintenance of community.

Were you at Notre Dame last week, Michael? Or where did you run into Ruth? I haven’t seen her in a while, but I consider her an old friend.

A very interesting point Russell; one I had not considered. My own experience with Christianity is that at its best it can support both local relationships (at least of a specific kind) and a generalized humane connection to all others. I guess the concern that it raises in my mind is the relationship that even this form of Christianity encourages with other faiths or the non-believer.

I remember being asked when I first moved to Jonesboro, Arkansas whether I had found a church home yet, even though I was not interested in finding one. I remember being taught as a young man all of the reasons why Mormonism was a cult. My wife, who is from Romania, simply cannot understand why United States churches send missionaries to countries such as her own or the Ukraine, both of which are Orthodox Christian countries.

I am not sure these are necessary results of Christianity at its base, but the call to preach the gospel and the claim of Jesus–“I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me”–seems to be important to most varieties of Christianity. There are similar sentiments in other religions as well. If we place religion at the center of any attempt to revitalize local connections, are we not inviting, not Luddism, but a divisive undercurrent that will eat away at any attempt to build community unless all conform? We do not have to do away with religion, but why give it as important a role as Chesterson seems to do?

I was not at ND last week, but at Yale where she gave a talk.I have found that geographically, the Northeast does have its advantages over other parts of the country. I really enjoyed meeting her.

Russell, I don’t think one even has to reach for the properly conceived Christianity to show that it is not a threat to locality and particularity, one need only look at the real, existing Christianity in history to realize this. Consider the Church at her political zenith in Middle Ages, before the Protestant Reformation. The Church was indeed the universal Church (in the West…) with no rivals anywhere, yet Western Europe was as divided and local as it is nearly possible to be. Only after the decline of the secular fortunes of the Church do you see the absolutist states rising, and always at the cost of the Church.

Also consider how Christianity absorbed and transformed local culture and folklore from pagan societies, instead of obliterating it. Contrast this with Islam, for example.

Oh, how I love humanity

With love so pure and pringlish;

And how I hate the horrid French

Who never will be English.

The International Idea,

The largest and the clearest,

Is loving all the nations now,

Except the one that’s nearest.

The villas and the chapels

Where I learned with little labor,

The way to love my fellow man

And hate my next-door neighbor.

–G. K. Chesterton

That says it all.

Good post. I feel compelled to bring in Dostoevsky:

“It’s just the same story a doctor once told me,” observed the elder. “He was a man getting on in his years, and undoubtedly clever. He spoke as freely as you, though in sarcasm, in bitter sarcasm. ‘I love humanity,’ he said, ‘but I wonder at myself. The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular. In my dreams,’ he said, ‘I often make plans for the service of humanity, and perhaps I might actually face crucifixion if it were suddenly necessary. Yet I am incapable of living in the same room with anyone for two days together. I know from experience. As soon as anyone Is near me, his personality disturbs me and restricts my freedom. In twenty-four hours I begin to hate the best of men: one because he’s too long over his dinner, another because he has a cold and keeps on blowing his nose. I become hostile to people the moment they come close to me. But it has always happened that the more I hate men individually the more I love humanity.”

[…] good summary of it is posted at Front Porch Republic. | | | | | […]

[…] G.K. Gets Real: “The danger of small communities is narrowness, but their advantage is reality. Now, at any specific stage in the world’s history we ought to ask ourselves whether humanity is in greater danger from the narrow arrogance of small people, or from the phantasmal delusions of empires.” […]

GKC’s Patriotic Idea can be read in its entirety here:

http://glad-thereafter.blogspot.com/2007/11/patriotic-idea-g.html

[…] G.K. Gets Real by Patrick Deneen […]

[…] Distributism defends. (Mark Mitchell has written on Hilaire Belloc twice, and Patrick Deneen on G.K. Chesterton, so perhaps Distributism will have struck some readers as more obviously informing FPR than I […]

Comments are closed.