Everything seeks its own perfection or completion, and, moreover, seeks this perfection in a way proper to itself. Since both the end sought and the way of seeking are attuned to the thing’s nature, actions can violate a thing’s integrity by working at cross-purposes to either the proper end or the proper way.

For many things, and particularly the human things, actions which are in keeping with a thing’s given end but pursue that end in the wrong way can be as destructive to the thing as consciously choosing to violate the end. As such, one may in good conscience intend to pursue the perfection proper to something but through negligence or carelessness utterly destroy it by going about that intention in the wrong way.

Going about it too quickly, for instance. Some things just can’t be hurried without causing real damage to what you seek. Virtue can’t be rushed. Romance probably takes some patience. Gardening, animal husbandry, child-rearing, education—all of these practices are impaired when sought more quickly than their intrinsic limits allow, and no technique or chemical or trick can replace time and the knowledge of the art.

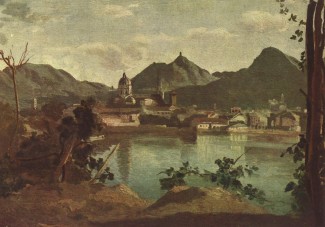

In his majestic Letters from Lake Como, Romano Guardini articulates how the work of bringing living form to its completion is the work of generations, and accelerating beyond that pace helps neither the work nor the worker but tends to damage both. Viewing the lake country of northern Italy, he notes the ubiquity of human artifice: the human mark is everywhere, virtually indistinguishable from its natural dwelling place. In fact, so embedded is culture that it seems to have followed the patterns of creation itself in proceeding slowly: “How long a cathedral took to build! How slowly a city came into being! And looking at the larger picture, how slowly history takes its course, the stream of living development … the forging of relations and forms in thought and life.”

Not only buildings and art, but also social order, which sought “possibilities … without either force or haste.” And since the means—in this instance the pace—of seeking the ends operated in keeping with the formal possibilities of reality, the “things integral to life found their appropriate forms.” Examples are easier to place when it comes to external works, such as traditional architecture or urban planning, or the liturgy, and perhaps more difficult to specify when it comes to the human, but Guardini suggests that “human types,” just as the physical forms, developed over the “long generations” in ways “disciplined and made capable of playing a full historical role.”

It took time, but the work of tradition was to bring, in great patience, the possibilities of humanity into existence without violating the limits of those same capacities, and so a “developed humanity has slowly achieved clearly evolved forms and has developed ways of seeing, owning, living, thinking, ruling, and creating.” The human things emerged in keeping with the human limits.

Operating within the limits of form, and at an ordered pace, the culture-making human was able to recognize themselves in their work, even, in some way, to be identified with it, and to understand that their own well-being was caught up into the well-being of the work, which is why the farmer could feel he had lived well if he handed on fertile and well-kept soil to his son, or a mason could take ownership in a yet-to-be completed cathedral, or an aristocrat might understand that her own comfort was secondary to the maintenance of the estate’s traditions. Tradition brought human form—roles—into existence as the product of human art just as the more tangible marks of culture in buildings and music and even the landscape, and in close relation.

Perhaps this is why, as Werner Sombart noted, “every monastery, every town hall, every castle of the Middle Ages bears testimony to the transcendence of the individual’s span of life: its completion spans generations which thought that they lived forever. Only when the individual cut himself lose from the community which outlasted him, did the duration of his personal life become his standard of happiness.”

One might die before the work is complete—but no matter, for one can reasonably anticipate the work continuing, in recognizable form and pattern, as an organic development from the present.

But now? Chuck Klosterman claims that cultural continuity changes about every four years, and so what purpose could there be to building or planting in hope of the future. The great-grand children for whom one works would not stand in cultural continuity and receive the work as an inheritance. Money can be passed down, but not culture, apparently, and so any cultural work one hopes to accomplish must be finished within the span of a single life. That is, in a rush, in a hurry, and the lapidary work of real culture turns into the vulgarity of those desperate to etch a name into the ephemera of “likes” and “views.” Trashiness ensues, for one must be noticed NOW or never.

According to Guardini, “the human measure has disappeared” and “there is no proportion of any kind, whether in big things or little.” But more, I’d suggest, too, that the measured human is also threatened. It is not just that our works get too big and fast for us, but that we become disproportionate in ourselves, incapable of finding that ratio by which to keep things in place and order.

We see it everywhere, do we not? The vulgarity. The cheapness. The trashiness. And the strange pride of our own complicity, even a celebration of it. For just as the world of slow growth allowed the emergence of character types in keeping with nature, so too does our pace create character types. Jackass. The Kardashians. Party Down South.

Nor can the tide be turned by individuals opting out, for cultural work is always that of solidary and over generations. And where is that to be found?

I recently read an excellent book called “Willpower. Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength” (co-authored by a leading experimental psychologist, not what you’re probably thinking, a self-help con)

I read the book because I was have trouble spending enough time in the garden, especially weeding. many of the scientifically discovered tips in the book got me working but one thing that stood out was how much more slowly I was working, enjoying the work & no longer making mistakes like pulling out non-weeds.

I like to think of it as working at a “luxurious” pace, work & leisure become one.

Said the wise Water Rat — there is almost nothing in the world so much worth doing as messing around in boats — just — messing — messing around — in boats ….

Could you tell me where that Sombart reference came from? It sounds like a book worth reading.

Comments are closed.