[Editor’s note] President Washington, in his original Thanksgiving Day proclamation, insisted it the “duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God,” and to be “grateful for His benefits.” Washington also gave thanks for our liberty and our temporal prosperity. It is easy in contemporary America to forget this. “The greatest country in the world” is a cliche that too readily trips off the tongues of many Americans, as well as paper-thin references to our freedoms and our wealth. America might not be as great as many of its jingoistic apologists hope, but neither is it as bad as its jaded cynics fear. It is right to remember that we enjoy in this country remarkable levels of personal freedom that, even if abused, contributes mightily to human flourishing. We enjoy almost inconceivable levels of material abundance, having unsaddled (to a degree) some of the riders of the apocalypse.

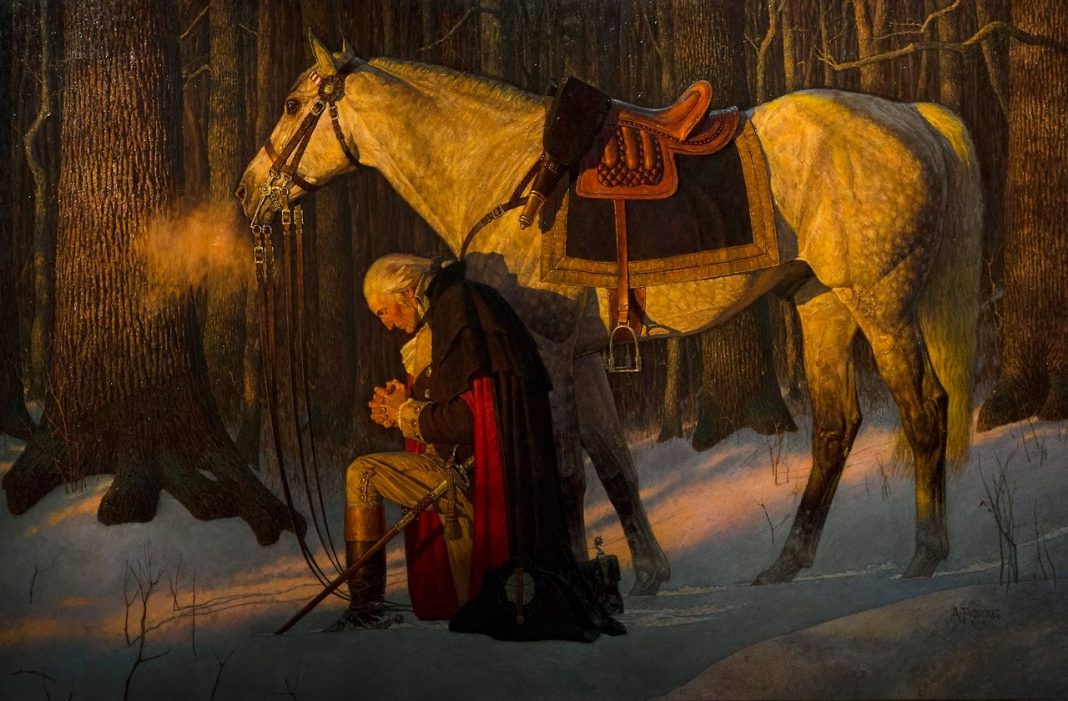

Washington’s invocations of “Almighty God” and “divine providence” now ring hollow to us, hand brought to their knees by the admonitions of those critical of civil religion, and on the other side by a skeptical secularism and public pluralism. Furthermore, historical scholarship casts into doubt the religious sincerity of persons such as Washington, or Lincoln, whom in his Thanksgiving address claimed that the great blessings of this land were “the gracious gifts of the most high God,” ones that “no human counsel nor hath devised nor mortal hand worked out.”

We’d do well to take these claims seriously, as did their authors. If there is a God, and if the God is providentially at work in this, the world of His creation, then it behooves us to think on the ways in which we, as a nation, are part of God’s providential plan. While it may be hubris to assign to ourselves a central role, it may be false modesty to suggest we have none. But anyone so blessed would do well to take a day of thanksgiving, if for no other reason that expressions of gratitude are properly humbling and restorative.

Today’s writers provide us with their brief reflections on Thanksgiving, and its significance. They are Daryl Hart, Mark Mitchell, and Susannah Black. We trust you will enjoy their reflections, and we wish to each of our readers and their families a joyous Thanksgiving.

Susannah Black

All things come of thee, and of thine own have we given thee.

I Chronicles 29:14

Think about shopping. You go into a store, you examine three different pairs of tights, you decide on the ones with Waldo-like candy cane stripes on them. You pay with money you earned; everything in the transaction comes from and returns to you. This is the ordinary mode of life in our cities and malls: you express yourself, impress your personality on the world, by what you buy: what you choose and pay for shows who you are and proves that you’re able to summon the resources to make that exchange.

The way of living that’s centered on thanksgiving is different. Gratitude starts with two basic facts: the existence of anything at all, and the existence of you. Neither of these things are you in the least responsible for. (No offense.) You didn’t ask to be born; you didn’t ask God to create the universe; and yet here you are, and here are all these trees and nebulae and bonobos and pairs of tights and laws of logic and other people and recipes for stuffing: all this existence, all the animals in the sea that no-one will ever lay eyes on, every oyster on every reef and in every batch of stuffing: you didn’t earn any of it.

What do you do with that? I don’t actually know, mainly because I haven’t read Peter Leithart’s book, and I even skipped the First Things booktalk on it a couple of months ago, and I’m aware that he’s the Official Gratitude Guy at the moment. Still I will make an attempt, despite this defect of research, to say something about how gratitude works in our lives.

Receiving a gift is an uncomfortable thing for a modern person to do, especially when that gift is the gift of existence, which makes demands on us. Obligations, in the classical liberalism that undergirds modernity, are those things which are freely entered into by the choosing rational man. But in the world as we actually experience it, we’re born into the gift of obligation and relationship just as much as we’re born into the gift of oxygen, as much as we are given our mothers’ blood through our umbilical cord before we are born. We’re given life: we may not throw that gift away through suicide or bad stewardship or sin. We’re given relationships and obligations; we’re called to honor our fathers and mothers who we didn’t choose; to obey governing authorities whom we may or may not have a part in choosing; to be our brothers’ keepers.

Modern natural law talk tends to break this law down into what we call “rights” and “duties.” We see the rights as the fun happy things, the cheesecake of the natural law, whereas the duties are its broccoli. We may– occasionally– recognize “rights” as things which are given to us– gifts with which our Creator endows us, in the language of American scripture, gifts for which we might conceivably be thankful, although the very language of rights tends to preclude this. We rarely, however, see duties as gifts. This splitting apart of the good into airtight categories– goods which we are owed and goods which we owe others– is, however, completely artificial. It’s as though we split love into other-people-loving-us, which is good because we are the recipients of something, and us-loving-other-people, which is bad because we have to give something. All good things– the moral law itself as well as Christ’s life which fulfilled it on our behalf– are gifts. To be called by God to worship Him is a gift.

To a modern person, committed to self-chosen obligations only (and to them perhaps only provisionally) this being-born-into, this network of relationships and good things to which we’re called, can feel oppressive– even though the things themselves may be recognized as good. What if I don’t want to be my brother’s keeper? What if I don’t want all these good gifts? The mystery of the refusal of the given good– ingratitude, to one’s own detriment– is one aspect of what Christians call original sin.

What Christianity recognizes is the strange fact that the acceptance of good gifts, delight in what is given, joyful response to loving benevolence on God’s part or that of our friends and parents, is both totally natural– and somehow, sometimes, weirdly hard. We know how to rejoice in good gifts, and we even know how to give them– “who among you, if his son asks him for a fish, would give him a snake?” We know this– sometimes. But then we fall down; we’re inconsistent in our ability to give and even to receive the good.

The classical world knew about gifts, and about gratitude: it was what is called now a gift economy, which is very easy to romanticize; in truth it often came down to something like the transaction between a mafia don and a Hoboken shopkeeper. And where it wasn’t that, there was always an element of building one’s own glory on the humiliation of others. The braggy and coercive version of generosity that the classical world knew– where your glory was measured by the lavishness of your gifts, but the good of the recipient was lost in the shuffle– was, however, a corruption of something good.

Christianity restored generosity precisely by showing God to be something that made no sense among the pagans: a humble gift-giver. God enacts and displays His glory in his real affectionate love of us, in all the good gifts he gives– most especially the gift of Himself. What Christianity brought was the knowledge that the “transaction” between patron and client was always, paradigmatically, one of love– intense desire for the good of the client on the part of the patron, and affection and rejoicing in the gift and the giver on the part of the client. This genuine, hearty, joyful gratitude is one of the most delicious things that a human can experience: it’s part of the mystery of the Trinity that God himself experiences this delighted, humble gratitude to God. Astonishingly, the gift that Jesus seems most eagerly to desire from His father is us: His people, restored to him.

What Christianity also brought was the recognition that gratitude itself– the ability to respond rightly to the reality of gift, to delight in the good, to give thanks– is at its heart another gift, and one which is, as I said above, imperfectly exercised. To grow up, to grow spiritually, is to grow more grateful: we are not now a thousandth as grateful as we will be in the New Jerusalem, because we’re not yet truly sane– that is, holy. How do we cultivate this gift of gratitude in ourselves? We know it’s one God wants to give– gratitude is something we’re called to, an accurate response to reality; ingratitude is a sin we’re called to forsake, as well as a deeply unpleasant state of mind to experience. If we know God’s willing to give us the gift of gratitude, what do we do then?

Well, obviously first pray for it. Ask for it more; be shamelessly greedy for gratitude. And then make two things part of your daily life: attentiveness and generosity.

Attentiveness is noticing the world– it’s where the gift of the world and the gift of yourself as a subject perceiving it intersect at every moment. Distraction, inattentiveness– these are bad stewardship of both these gifts. Notice the outside world– all the things you didn’t make that are poured out for you; all the gifts of energy and ability that are yours to cultivate.

And then use these gifts to make things, and give them to others. That’s how this is meant to be played out– by using our gifts fruitfully and then giving what we make away generously, we are as it were tuned to reality, tuned more and more to be able to respond naturally to what God himself gives, tuned to be able to love and be loved. Cooking is, of course, an excellent opportunity for this kind of attentiveness, fruitful response, and generosity; I’m on the lookout for an oyster stuffing recipe at the moment, if anyone wants to post one in the comments. I’m also interested in anything involving roasted or caramelized vegetables.

The Greek language that Paul so astonishingly reappropriated in his letters had a rich vocabulary of gift-giving. A great lord would extend charis, grace, to a client in the form of a gift or favor, to which the client would respond with pistis: trustful fidelity, loyalty, reliance. The word that we have for the Lord’s Supper– Eucharist– echoes this: it is literally good-grace, but it’s translated more colloquially, of course, as Thanksgiving.