Our Only World: Ten Essays. By Wendell Berry. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2015.

In January of 2012, Wendell Berry delivered a speech at Georgetown College that explained his support for legalizing gay marriage. Responses from Berry’s Christian readers came thick and fast; most of these wrestled with the difficult, if not impossible task of reconciling Berry’s previous descriptions of marriage with his newly-stated support for gay marriage.

Such approaches are certainly helpful and illuminating, but Berry’s views on marriage can only be understood from the perspective of his broader agrarian vision. The appearance of Berry’s revised speech in his new collection of essays, Our Only World, offers an opportunity to consider his stance on gay marriage within the context of his wide-ranging critique of industrial culture. In fact, Berry believes discussing marriage as an isolated issue is symptomatic of the improper specialization and division that plague our culture. Throughout these essays, Berry describes the far-reaching consequences of an industrial way of life, one that replaces the sacraments — which unite spiritual and material — with a commerce of violence — which reduces life to its material components in order to more readily profit from them. Healing, Berry argues, comes when we take up the difficult, slow work of kindness, imagination, and sympathy, work that becomes sacramental by treating “the world and its creatures within a context of sanctity in which their worth is absolute and incalculable” (Imagination in Place 32).

Christian readers may not agree with the prudence of Berry’s political advice regarding gay marriage, but they can at least commend Berry’s efforts to place this debate within the context of our larger cultural malaise.

Our Only World, like Berry’s other essay collections, covers an impressive array of subjects: poetics, the Boston marathon bombing, sustainable forestry, abortion, gay marriage, Edward Snowden and the U.S. secret surveillance programs, strip mining, water quality and the 2014 chemical spill in West Virginia, species loss. Berry draws these disparate topics together to provide an authentic general criticism, a kind of thought not often practiced in an intellectual culture infected by industrial specialization: “We have good technical or specialized criticism: a given thing is either a good specimen of its kind or it is not. A valid general criticism would measure work against its context. The health of the context — the body, the community, the ecosystem — would reveal the health of the work” (14).

While Berry freely acknowledges his gratitude for the particular benefits specialization has brought — painless dentistry is a good thing — a valid general criticism must provide a more nuanced accounting for net gains and losses:

… valid criticism does not deal in categorical approvals and condemnations. Valid criticism attempts a just description of our condition. It weighs advantages against disadvantages, gains against losses, using standards more general and reliable than corporate profit or economic growth. If criticism involves computation, then it aims at a full accounting and an honest net result, whether a net gain or a net loss. If we are to hope to live sensibly, correcting mistakes that need correcting, we need a valid general criticism. (13-14)

In seeking to practice such a criticism, Berry’s essays range beyond any disciplinary boundaries, testing our culture against the health of its context.

The passage quoted above also illuminates one of the statements in Berry’s speech on gay marriage that has drawn the most criticism. Speaking of the ease with which religious judgments against sin become judgments against categories of people, Berry states: “Condemnation by category is the lowest form of hatred, for it is cold-hearted and abstract, lacking the heat and even the courage of a personal hatred” (94).

Some, like Christopher Roberts, have read this as a bitter attack on a straw-man version of those who defend traditional marriage. Indeed, Berry may be painting with too broad a brush here, but his real point is that condemnation by category, wherever it is found, is a shortcut that serves the industrial desire for quick profits or easy victories. In another essay in which he critiques industrial farmers, he returns to this danger, admitting his own temptation toward such lazy, oversimplified thinking: “The rhetoric and indignation of conservationists often leads to stereotyping and condemnation by category. I need now to be careful to avoid that” (114). Thus he acknowledges that many farmers who use industrial methods are good people, constrained by perverse economic systems and incentives. Berry warns against categorical condemnation of any person, then, because it hinders an honest, nuanced accounting and functions as one of the reductive transactions that perpetuates “the commerce of violence” (17).

In the essay titled “The Commerce of Violence,” Berry mourns the tragedy of the Boston marathon bombing while urging us to look beyond the latest horror in the news to see the ways in which we participate daily in similar forms of violence. Strip mining, which destroys “a mountain, its forests, its waterways, and its human community without counting the destruction as a cost,” drone warfare, the Boston bombing, Guantanamo, all these are transactions in the same economy (16).

This economy thrives on the “cheapening of human life,” and Berry exposes our complicity in such a reduction so that rather than scapegoating the latest extremist or terrorist, we will begin practicing lives that value other humans: “It is not possible for us to reduce the value of life, including human life, to nothing only to suit our own convenience or our own perceived need. By making this reduction for ourselves, we make it for everybody and anybody, even for our enemies, even for the maniacs whose enemies are schoolchildren or spectators at a marathon” (17). In other words, the violence that characterizes our contemporary life thrives on a false “devaluation” of human life.

This insistence on the sanctity of human lives forms the core of Berry’s essay on gay marriage. He begins “Caught in the Middle” by insisting that laws cannot coerce loving care: “The appeal to government is made, whether or not it is defensible, when families and communities fail to meet their prescribed moral responsibilities” (74). In an essay on local economies, he makes this same point: “We must reject the idea—promoted by politicians, commentators, and various experts—that the ultimate reality is political, and therefore that the ultimate solutions are political. If our project is to save the land and the people, the real work will have to be done locally. Obviously we could use political help, if we had it. Mostly, we don’t have it” (63).

Interestingly, Berry seems to think that government policies might “provide some checks against” damaging environmental practices (50), but, given our particular cultural situation, he does not think the government can helpfully inhibit homosexual practices (although presumably he would support legal checks on some forms of sexual behavior). His focus in this essay is on “homosexual marriage as an issue of law” (87), and his conclusion is that Christians perpetuate a culture of violence if they insist on trying to force their view of marriage on a society that has rejected it. As the term “culture wars” indicates, Berry is not alone in this assessment.

Berry’s goal in this essay, as its title “Caught in the Middle” suggests, is to find an elusive common ground on this contentious topic. So, for instance, he does not take a position on whether homosexual acts are sinful or not. He concludes the essay by describing Christ’s forgiveness of the woman caught in adultery, and while this implies an analogy between adultery and homosexuality, his point is that Christ shows kindness to sinners and that a Christian’s first duty is to likewise show kindness. He sees the legal battle over marriage as part of the “industrial-capitalist” logic of force, and as an alternative he suggests the difficult work of love: “Heterosexual marriage does not need defending. It only needs to be practiced, which is pretty hard to do just now. But the difficulty is rooted mainly in the values and priorities of our industrial-capitalist system, in which every one of us is complicit” (92).

Fighting for marriage through legal force, Berry thinks, distracts Christians from the primary task of practicing love, a love that must include even one’s enemies. Love cannot be coerced; it can only be given. And love can only be given on a personal scale, in marriages, families, communities, churches.

Given his reasoning, I think Berry might actually be very sympathetic to First Things’ “Marriage Pledge,” which advocates separating civil marriage from the Christian sacrament of marriage. He seems unable to take this final step, though, because of his diffuse ecclesiology. As his fictional character Burley Coulter famously states, drawing on St. Paul’s metaphor for the church, “The way we are, we are members of each other. All of us. Everything. The difference ain’t in who is a member and who is not, but in who knows it and who don’t.”

This is the ecclesiology Jason Peters recently “tweaked,” and it is the view of membership Berry endorses at the conclusion of “Caught in the Middle” when he writes, “From the point of view of Genesis 1 or of the 104th Psalm, we would say that all are of one kind, one kinship, one nature, because all are creatures. Much happiness, much joy, can come to us from our membership in a kindness so comprehensive and original” (96). As Berry’s language of membership suggests, the sacred membership of creation derives from the sacred membership of Christ’s body, the church, yet by flattening these two into one membership, Berry loses the distinctions needed to maintain the sacrament of traditional marriage. While such a broad view of the church sacralizes all our interactions, it also prevents Berry from imagining the church as a human institution that has divine authority to bestow or withhold sacraments.

Berry’s diffuse ecclesiology may make his position on gay marriage ultimately dissatisfying to some Christian readers, and in this regard his thought stands as a reminder that Protestant Christians ought to consider their ecclesiology more carefully. Nevertheless, his admonition that marriage names not just a contract between two people but a form of love that should guide our entire way of life should be heeded, and indeed it parallels Pope John Paul II’s warnings against our far-reaching “culture of death.”

Throughout these essays, Berry challenges readers to embody “a practical and practicing love” as the only way to fundamentally opt out of our commerce of violence (116). And marriage remains, for Berry, the form of this love. As he writes when critiquing specialized, industrial modes of thinking, “there has always been a higher seeing that informs us that parts, in themselves, are of no worth. Genesis is right: ‘It is not good that the man should be alone.’ The phrase ‘be alone’ is a contradiction in terms. A brain alone is a dead brain. A man alone is a dead man” (4-5). Thus, the most fundamental rejection of our culture of violence would be to refuse to be right through means that leave us alone. Such pyrrhic victories fail to honor our obligation to practice kindness to all the members of creation’s kinship.

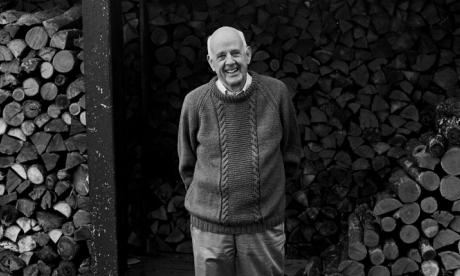

(Image source)

I’ve always been fond of WB, and I’ve disagreed with him on several issues, and SSM is another.

The question re: the recent contretemps is about secularists compelling ‘participation.’

If we are to take revelation seriously then supporting SSM is supporting a mocking of God’s revealed order, a blasphemy of the first order.

A sexually active homosexual exists in a condition of sin in the same manner as an adulterer, etc. and that’s their business. Just don’t ask me to condone, support or participate in it.

I agree with you, Mr. Cheeks. As much as I see things as Mr. Berry does in his overall view and approach to our current plight, he seems sometimes just a little too nuanced or even “too clever by half,” especially when it comes to something like SSM.

Still, even in what I consider error, Mr. Berry is more formidable, more enlightening, than many who are orthodox! I suppose there’s something to the idea that had we maintained our priorities, emphasizing the proper nurture and “husbandry” of our marriages, families, churches, communities – along with the places in which they embody themselves – instead of inappropriately delegating our responsibilities for same to “experts”, the government and its “corporatocracy”, we likely wouldn’t be in this position now. This isn’t an either/or proposition, but a both/and: we have to work politically and legally while prioritizing things at the most local level, namely, our marriages and families. Indeed, the best argument for God’s design in marriage is in fact one wherein the husband and wife properly submit to His design not merely for their sake, but for their families, their churches, and their communities.

No doubt, I’m making some intuitive leaps here, but I hope this makes some modicum of sense.

Cheeks!

Back from the barricades! He has risen indeed!

But alas, WB is right. As per usual. It’s a shame FPR is slowly succumbing to a degenerative Catholic myopia.

[…] (Wendell Berry via Jeffrey Bilbro) […]

“But alas, WB is right.”

On what, specifically? And it has to do with “Catholic myopia” how?

(For the record, I’m not Catholic, just curious.)

I think WB has it nailed in regards to same-sex marriage… that you can’t fight for marriage through legal means… that as Christians we are called to love etc.

As per my comment on Catholic myopia, I have been disappointed by FPR’s drift away from being a “place” dedicated to place, limits and liberty, to a place where a large portion of content seems to be about the Catholic Church.

I have no problem with Catholicism as a particular Christian vernacular, but Catholic myopia always sets in when the Catholic twists himself or herself (and logic) into knots to justify or defend any one of the numerous Catholic tenets to the exclusion of other interpretations of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. There are many beautiful aspects to the Catholic faith, but the idea of the “one true Church” being the Catholic Church is a fatal idolatry, and again and again it seems to induce a kind of shortsightedness, or pettiness in dogmatic detail, that often seems to obscure the larger, broader and shared truths that those of us who fiercely love Jesus and his Creation seek to defend.

I appreciate and share WB’s suspicion and distrust of the institutional church, if WB’s attitude can be qualified that way. Suffice it to say I have strongly identified with all his essays or novels that touch on the institutional church.

“he does not think the government can helpfully inhibit homosexual practices”

Yes, what a terrible idea, using coercive government to impose a moral vision on people. I’m so glad Mr. Berry has the courage to stand up to the ascendant might of the Religious Right.

http://state-journal.com/local%20news/2013/08/29/frankfort-city-commission-passes-fairness-ordinance

Oh, well. As Anscombe put it, protests by people without power are a waste of time. You all & The Henry County Prophet have fun defying the establishment, with the aid of Bill Moyers, NPR, and the Louisville Archdiocese.

Yes, sexing around outside of marriage, before or after marrying, is something most of us are, or have been, guilty of. But the question should arise as to why the state has standing to dictate whom anyone might love and marry.

Just as atheism is a theological statement, so for the state to draw a distinction between civil and sacramental is for the state to make a religious distinction, which should be noticed as being out-of-bounds.

The churches are welcome to define their sacraments. (The Church – of which the Roman church is merely one of many aspirants – cannot be spoken for by humans in pronouncements, but only by actions of congregants, which speak louder than words.) Berry is right to invite us to illustrate our love of a particular spouse, and of our humane recognition of the rights of others to marry whomever they choose to love. Separation of church and state is unshakeable on this point.

So here was Berry’s chance to apologize in for the intemperance of his “Christian bloodthirst” and “condemnation by category” and other insulting remarks at Georgetown against Christian opponents of SSM, and it sound like he passed. Or, are Berry-followers aware of where he has done so elsewhere?

The Roberts’ piece you have the decency to link to is part analysis, but its more damning part is simply reporting. Of what Berry said. It’s not just the words, but the way they were played for cheap laughs.

Honest question: has Berry ever, since these remarks, said anything indicating he understands the difference between the more typical Christian social conservatives who oppose SSM, and the FPR-like and Berry-loving Christians who also oppose it (whether politically, or only theologically)? Has he exempted, that is, some of y’all from the standing charges of “bloodthirst” and “condemnation by category”?

I mean, one of the things that angered me about those Georgetown comments was the way Berry seemed totally silent about, and thus daft about or deaf to the position of FPR-like opponents of gay marriage, which to me suggested a lack of gratitude to all y’all have done to build his reputation. At a key moment, he couldn’t spare a thought for y’all. I’d be happy to learn he has apologized since in some back-channel way or subtle manner.

Strip mining…drone warfare, the Boston bombing, Guantanamo, all these are transactions in the same economy (16).

A man losing his judgment in old age is not very edifying.

Honest question: has Berry ever, since these remarks, said anything indicating he understands the difference between the more typical Christian social conservatives who oppose SSM, and the FPR-like and Berry-loving Christians who also oppose it (whether politically, or only theologically)? Has he exempted, that is, some of y’all from the standing charges of “bloodthirst” and “condemnation by category”?

I take that Mr. Scott fancies that those of us who are vulgarly ‘typical’ are properly describes as animated by ‘bloodthirst’ and engaged in ‘condemnation by category’. I can feel the love, buddy.

that you can’t fight for marriage through legal means…

I guess it was my imagination that there was this body of text in each state referred to colloquially as ‘family law’.

Nuance won’t make me respect an inherently silly position any more. Nonsense is nonsense.

Hey, Art. You misunderstood me. I am the more typical religious social conservative myself, pretty much. I was just trying to convey my sympathy for the situation Berry’s remarks put FPR-types in, types that want, for better or worse, to see significant distance between their stance and the more typical sort of social conservatism that aligns with magazines like First Things, with movement conservatism, with voting R pretty regularly, etc.

I disagree with that distancing, and especially at the bottom-line voting level. I’ve long been a friendly critic of the FPR stance. And my own byline appears over at National Review, and it used to at First Things.

While I certainly took offense at Berry’s categorical condemnation of myself and mine own, his refusal to even acknowledge the unique position of the various religious opponents of SSM who are with him on virtually every other issue seemed particularly low.

My regrets Mr. Scott. I’ll attempt to improve my aim.

One gets the feeling from some here that Mr. Berry is some sort of semi-deity. To me he comes across more as a goody two shoes leftist. I used to read his work, but after his insults, no more. There are many other, better authors to read during one’s limited time on this planet.

Comments are closed.