Trees cannot talk, but they do speak. With our eyes focused on franticly flickering screens, perhaps our ears have grown dull to their still small voices, yet they whisper on. Edmund Burke described society as a “contract between the past, the present, and those yet unborn.” Great trees transcend human generations, and so they quietly testify as living contract witnesses to a past no earthly soul can recount and often remain through a future that even the brightest eyes of today will not see. But trees too are mortal, and memorializing their service can produce unexpected and not so subtle sounds — like the roar of a chain saw.

James Phillips’ big break was a hurricane, but the possibility of much gentler spring rains pushed matters indoors when I met him at a small town fundraiser. With shaggy white hair streaming down from under a cowboy hat, the friendly, self-effacing, self-taught artist who transforms tree trunks into sculpture still looks very much like the working class denizen of the Texas chemical coast that he long was. He began by tinkering with the remains of a tree in his own backyard, and then in 2008 Hurricane Ike produced a plethora of canvasses in his hometown of Galveston. With an assist from a regional TV show, word of his hobby spread around the Lone Star State. Phillips eventually had enough commissions to quit his day job and pursue his passion full time. Now he bounces around Texas giving dead trees new life as open air art.

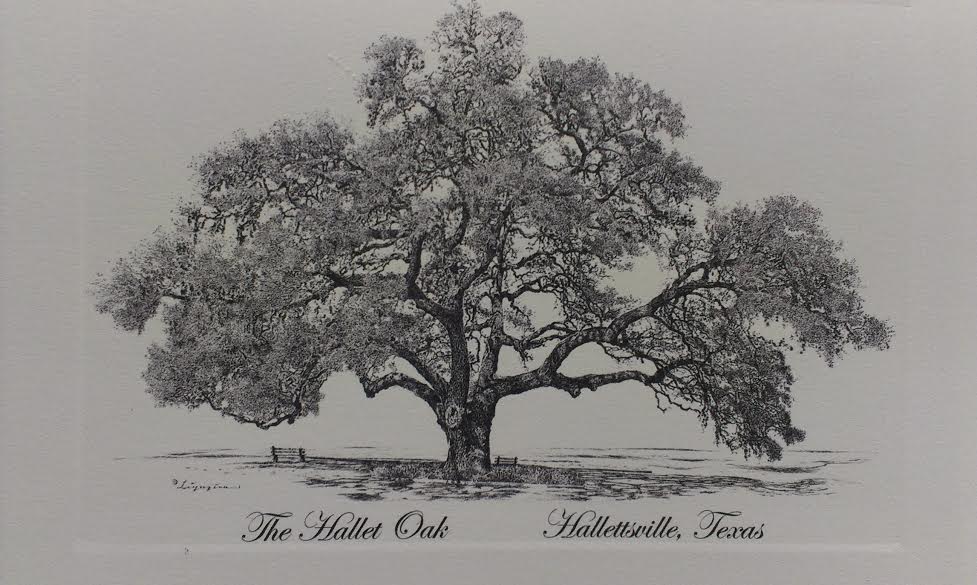

The Hallet Oak has stood for over 250 years, and is so called because it cast its shade near the home of local white pioneers John and Margaret Hallet, from whence the town Hallettsville draws its name. Arguably, the naming should have gone the other way. The Hallets did not plant the live oak, instead they planted themselves by it, already well rooted for over a half-century when they arrived in 1833 (Another local community also centered around an impressive stand of ancestral trees took the less anthropocentric route of naming itself Oakland.) Regardless, while John Hallet was dead within a year of building a small log cabin and the resolute Margaret persevered for another thirty, their arboreal namesake stood tall even longer as the growing community of people traversed through the Texas Revolution, the Civil War, two world wars and various social revolutions.

About a decade ago, however, the Hallet Oak, today surrounded by a city park, began to show signs of distress. Experts were brought in, but to no avail. A record drought likely did not help matters, and by 2014 it was clear that no new growth rings would be added to the impressive total.

Dead trees in public places, even famous ones, do not often get much of an afterlife. The National Christmas Tree, a living spruce lit each year by the First Family in one of Washington’s nicer non-partisan traditions, was snapped by high winds in 2011. In a rare show of government efficiency, it was reduced to mulch within seven hours of its demise. Speedy? Yes. Sensitive to the memory of the Pennsylvania family that had hand watered and later donated the tree or the thousands who long enjoyed Yuletide visits and might have welcomed an ornament hewn from the wood of an old friend? No.

Queen City, the small East Texas town where I was raised, boasted no actual royal connections. Its most regal resident was a champion water oak, a massive specimen long ignored before finally being honored with a sign in the 1980s. Just a few years later, a vicious thunderstorm reduced it to a limbless hollowed out trunk with just a sprig or two of green remaining. The sign soon came down. Eventually, so did the remnants of the once towering tree itself, leaving no trace of its time on earth that extended back to the days when kings, queens, and chiefs vied to rule the land around it. Today, most of the transient residents in the nearby Water Oak Apartments likely have no idea why their abode bears the name it does, if that name is even used at all anymore.

To their credit, the inhabitants of Hallettsville, a hamlet with more regard for tradition than most, did not hastily abandon the Hallet Oak to the wood chipper and the stump grinder. Its once mighty canopy, in danger of injuring rather than shading the children that played nearby, was pruned back so that only two strong but leafless arms stretched out in truncated fashion. Townspeople then rallied to raise the $10,000 needed to bring in Phillips and his creative chainsaw. Most of that money came from a well attended silent auction that featured everything from shelled pecans and chocolate chip cookies to quilts, a barbecue grill, and a bonsai tree up for bid. I walked away with one of ten bottle stoppers made by the aptly named John Carpenter who had crafted them from a branch of the historic tree and topped each off with a buffalo nickel. The ornamental flourish was not by chance.

Now that the sawdust has settled, two American bison stand atop the Hallet Oak’s wooden pedestal. The bison gave the river near which the Hallets settled its name. Early Spanish explorers, noting the many bison grazing at its mouth, referred to the flashy stream as the river of the cow, or “la vaca.” Today, the Lavaca River rises in Lavaca County (governed from a stately 1897 courthouse in Hallettsville) and cuts its short 115 mile path to the Gulf of Mexico where it empties into Lavaca Bay. Of course, the buffalo no longer roam along its banks, killed off in the rapaciousness that too often marked the drive to civilize the frontier. But, the beasts again stand in the centuries old wood of the Hallet Oak, a testament to both the good and bad that people have brought to this land.

Such an act of present tense civic remembrance is simultaneously a fruit of the past and a seed for the future. And may the acorns of today grow into the great oaks of tomorrow.

John Murdock writes from a century old farmhouse built by his great-grandparents and enjoys visiting the ancient live oak a few yards away that has stood for several centuries more. His online home is johnmurdock.org.

[…] How can trees help us? And how can we help them once their leafy days are done? I investigate up on the Porch. Here. […]

[…] The lives of trees and their communities. […]

Comments are closed.