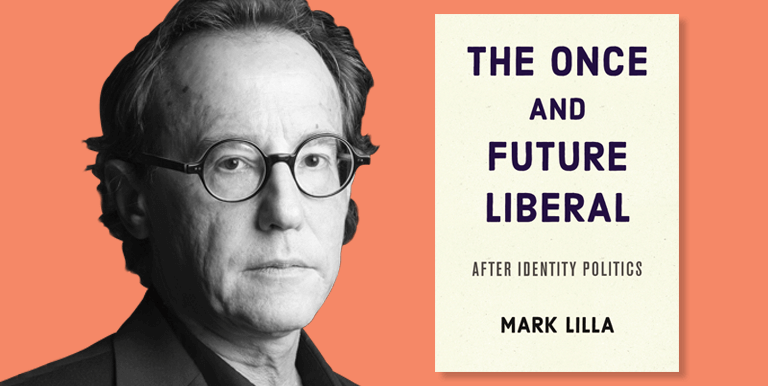

Shortly after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election, Columbia University professor Mark Lilla took to the pages of the New York Times to offer an edifying perspective as to why Trump won. While many causes contributed to Trump’s victory, Lilla places unique emphasis upon the political left’s inability to transcend the narrow scope of identity politics. Taking issues of class, race, or gender, and elevating them as the central political concerns not only distorts these issues but other important matters as well. In fact, Lilla laments, arguing that other issues besides these have equal moral and political weight ensures one will be labeled xenophobic and racist. By framing matters around individual markers of identity, the political left has thus been able to provide a meta-narrative lumping people into one of two groups: everyone is either liberal or “illiberal.” This reductionistic division and caricature has been aptly described by Ofir Hairvy and Yoram Hazony:

there are liberals—those decent persons who are willing to exercise reason in the universally accepted manner and come to the appropriate liberal conclusions; and there are those others—the “illiberals,” who, out of ignorance, resentment, or some atavistic hatred, will not get with the program. When things are divided up this way, the latter group ends up including everyone from Brexiteers, Trump supporters, Evangelical Christians, and Orthodox Jews to dictators, Iranian ayatollahs, and Nazis.

Perhaps the most intellectually challenging feature of Lilla’s astute essay is his recommendation detailing what fellow liberals ought to do in response to the shallowness of contemporary liberalism. In essence, Lilla bemoans the destructive methodology that too-often characterizes the political left and so makes a case for fostering what he calls “a post-identity liberalism”:

We need a post-identity liberalism, and it should draw from the past successes of pre-identity liberalism. Such a liberalism would concentrate on widening its base by appealing to Americans as Americans and emphasizing the issues that affect a vast majority of them. It would speak to the nation as a nation of citizens who are in this together and must help one another.

In conjunction with this, Lilla alludes to the specific content of a post-identity liberalism, i.e., the knowledge of American democracy, the historical lessons drawn from this experience, or that which pertains to well-informed voting. These, it should be noted, are features of democracy as a kind of regime, and the various expressions of its political and institutional structures. However, the focal point here concerns not so much political democracy per se, but the liberal aspect of modern liberal democracy. According to Lilla, post-identity liberalism should be fundamentally characterized by its aim to draw from the past successes of pre-identity liberalism. In other words, the present form of liberalism is politically ill-equipped and exhausted. In turn, what is needed entails a recovery of a richer, and older, type of liberalism. This call to recover an older type of liberalism will be the primary object of critique in this essay. Nevertheless, while I critique the notion of liberal citizenship, Lila’s work helpfully identifies the exhaustion of contemporary, liberal conceptions of identity.

Lila’s work helpfully identifies the exhaustion of contemporary, liberal conceptions of identity.

The question being raised by Lilla is deeply important. It summons us to refocus on precisely what is meant by “liberalism,” and whether another, perhaps tempered, form is what can maintain a real civic and cultural order. In his book, Conserving America? Essays on Present Discontents, Notre Dame political philosopher Patrick Deneen provides an illuminating perspective upon what could be considered a first principle of modern liberalism:

Liberalism was advanced to perfect a rational system of inequality in which the “rational and industrious” would be rewarded for their achievements that could only come fully into fruition by minimizing any forms of deeply grounded social association or relationship. This system required dislodging people from a lived experience of embeddedness in family, culture, place, and tradition. Liberalism, as the name suggests, sought to liberate people from all the institutions and relationships that—in the view of liberal thinkers—had held people back from achieving the fullness of their potential.

In addition to Deneen’s assessment, the French Catholic political philosopher Yves Simon articulates a similar view in his book, Philosophy of Democratic Government. Simon argues that what makes modern liberal democracy unstable is not, as one might assume, the fact that it is a democracy. Rather, he places the deepest problem at the feet of liberalism itself:

preserving principles is more difficult in democracy than in any other regime as a result of liberalism, which implies that the principles of society and what its end is are not above deliberation and must be thrown into the universal competition of opinions. This is the jeopardizing of the principles without which social life no longer has an end or form.

Both Deneen and Simon have honed in upon a rather unsettling, even uncommon, interpretation of liberalism’s historical trajectory. Human beings were once understood to be intimately connected to those enriching institutions and forms of associative life such as “family, culture, place, and tradition.” However, the rise of early modern political and philosophical thought introduced a new manner of conceiving ourselves as cut-off from such realities. Aided by the Cartesian cogito, the Baconian reversal of the orders of contemplation and action inaugurating a new science of nature, and the “State of Nature” doctrine evidenced in John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, we have ironically become inheritors of a tradition that sees human beings as primarily individuals without context.

we have ironically become inheritors of a tradition that sees human beings as primarily individuals without context.

This new, self-created individual no longer depends upon those natural and humanizing associations that were given by nature, and God, to help us along the needed path of ordered liberty. As Simon observes, liberalism fundamentally calls into question, and eventually denies, the ultimate principles that ground our social and political lives.

Our identity as human persons can then be seen as deeply unstable as the result of liberalism. By undermining the content and teleology of human nature, and the various natural associative forms of life, the logic of liberalism becomes all the more intelligible as an explanation for the visible social disruptions and vitriol that have become normative. This conclusion, however, is grounded in envisioning liberalism within its own self-understood, logical trajectory. It seems correct to say that Lilla’s critique of contemporary liberalism is aimed towards progressivism, and that he hopes to make a strong defense for restoring a kind of orientation towards classical liberalism. Such an argument, it should be said, is not without truth and historical merit. However, the underlying insufficiency in such a formulation is that it begs the question. To claim that progressive liberalism needs to be countered with the tenets of classical liberalism neglects the truth that both are grounded in the worldview of liberalism, which Deneen describes as one of being released, liberated from “any forms of deeply grounded social association or relationship.” In this respect, we could initially posit that since the trajectory of classical liberalism prepares the way for progressive liberalism (of which Lilla rightly critiques), it would seem self-defeating to hope that our political discourse and life can improve by making appeals to more liberalism. The sort of liberal perspective that Lilla argues for is one that will only reinforce the very destructive kind he hopes will be overcome. This claim entails seeing both types of liberalism as different sides of the same coin.

It would be, nevertheless, dubious to deny the truth claims in Lilla’s argument. In a more recent essay, he writes that “Every advance of liberal identity consciousness has marked a retreat of liberal political consciousness. There can be no liberal politics without a sense of We—of what we are as citizens and what we owe each other.” Lilla is certainly on to something, saying that the way to overcome identity politics is not to reject identity tout court, but to focus on an identity that appears to be almost different in kind. In other words, there is an identity worth emphasizing, one more deeply rooted in human nature and the way human beings really are, ontologically speaking. And this identity, in accord with Lilla’s account, is citizenship. Even here, though, this notion of citizenship requires further specification, one which counteracts the liberal tendencies (defended by many on the left and right) supportive of global citizenship and a cosmopolitan disposition. The specification, in this context, is that of a more local citizenship grounded in the love of, and attachment to, home; an understanding of ourselves and our place in this world that Roger Scruton calls oikophilia.

In his magisterial work, The Quest for Community, the social scientist Robert Nisbet alluded to a similar argument regarding identity. For Nisbet, the autonomous individual as abstractly construed in modernity was left isolated, without context, and barren before the state. The decline of authoritative forms of “intermediate associations,” coupled with the rise of individualism, did not erase man’s natural inclination towards social life. Support for greater individual liberty has been, and will be, ill-suited to defend oneself against what Tocqueville called that giant “tutelary power.” As a response to the logic of both classical and progressive liberalism, Nisbet’s called for a new social and political philosophy, what he called a new laissez faire:

To create the conditions within which autonomous individuals could prosper, could be emancipated from the binding ties of kinship, class, and community, was the objective of the older laissez faire. To create conditions within which autonomous groups may prosper must be, I believe, the prime objective of the new laissez faire. . . . What we need at the present time is the knowledge and administrative skill to create a laissez faire in which the basic unit will be the social group.

How, though, can we think about the love of home, and the attachment consequent to it, in this context? It must be recalled that, according to Nisbet, those local intermediate associations of family, polity, and church exist as a protective check upon an all-powerful state. Additionally, these real, autonomous communities are considered necessary for man as the result of his natural ordination toward communal life. They provide an existential grounding and an orientation that gives purpose to one’s life. In this way, we could say that without such intermediate associations, human beings will experience a deep sense of loss and confusion. This results from the simple anthropological and metaphysical fact that our nature as social and political animals is not being fulfilled but is left vacant and waiting for completion. In such a condition, people become prone to a collectivist takeover by a Leviathan State, an “entity” willing to grant them freedom and protection to live as they so choose. Instead of people discovering meaning through the given associations mentioned, they can become disoriented and broken, failing to live their lives with any sense of interior order and telos. Self-rule becomes replaced with dependency upon someone else to arbitrarily and artificially grant us the freedom we ourselves do not possess.

In his book, A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural, Wendell Berry states that “A person dependent upon somebody else for everything from potatoes to opinions may declare that he is a free man, and his government may issue him a certificate granting him his freedom, but he will not be free.” In Berry’s judgment, a person whose entire way of life is characterized by dependency upon another, usually the remote other of a disinterested bureaucracy, is only nominally free. In Berry’s estimation, we must conceive of freedom within the context of ordered self-government, which is nothing other than self-ruling virtue. In this way, a different sort of autonomy can be lived and experienced in the world, something both real and authentic. Our personal agency is then no longer sensed as something distant. A virtuous person embedded in given communities can live an authentically free life and avoid the malaise of “alienation” that haunts contemporary liberalism.

Wherever ones stands on the political spectrum, this experience of “alienation” is acutely felt and evidenced in our contemporary lives, especially regarding this notion of attachment or love of home. More often than not, it seems that somebody else is tending to the care of our goods and property. This feeling of alienation and detachment is further exacerbated in our way of life as being more consumers than producers, giving in to the expensive, seemingly liberating, “domestic outsourcing.” And, although rates of geographic mobility have declined recently in America, it is still the case that we move with a regularity that makes it difficult to build lasting friendships with our neighbors and others in our communities. Likewise, the urban design that characterizes many places we live has left citizens feeling more anxious and unsituated. Affective attachments are weakened when we lack aesthetic space ordered towards bringing people together. Cities designed for machines and cars discourage neighborliness. As a result, it should not be surprising that our homes and neighborhoods are often vacant, with little activity apart from what goes on away from them. What all this means is that, in effect, the opportunities for actively caring for our places, deepening our love and attachment for them and those who dwell there, is continually declining. Additional consumerist drives, technological saturation, and the evisceration of robust local associations fosters identity politics as the end game in our angst to grasp for meaning.

In ways that are hard to imagine in a liberal society, when we devote ourselves to those cities, towns, and neighborhoods we call our own, we begin to experience genuine human agency. The “We” of such a community is not that of collectivism or global citizenship precisely because, among other things, it is grounded in an attachment to somewhere. As Yuval Levin argues, this attachment begins in the family and expands “to interpersonal relationships in neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, religious communities, fraternal bodies, civic associations, economic enterprises, activist groups, and the work of local governments.” This reality comes to fruition through the work of many years of our various traditions being passed down through socially-embodied customs and forms of affection. Devoid of this affection and attachment, the net result is an inevitable destruction whereby local self-government and virtuous care are replaced by the uninterested, detached other.

Some sort of positive account must be given that makes clear what it is that we should stand for, not simply what we are against. There always exists the continued possibility of revitalizing our civic and social attachments that flow from our love of home. In his book Green Philosophy, Roger Scruton put his finger on the fundamental tasks that seem before us hic et nunc:

The difficult part is that of putting oikophilia into practice. For it means combining with others in order to live the civic life; it means resisting entropy, whether it comes from below in the form of social nihilism, or from above in the form of oikophobic edicts; it means creating and sustaining neighborhoods. It means actively handing on to the next generation all that we have by way of knowledge and competence, and imbuing our successors with a spirit of stewardship that we also, in our own actions, display. This is hard work, requiring patience and sacrifice. But “better a dish of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred withal.”

A marvelous essay.

It has been argued elsewhere that Modern American Conservatism ™ is simply a variant of Liberalism, and Libertarianism is a distortion which extols the sins of Manchester. Utilitarian thinking has become so pervasive that both Left and Right seem not to know any other arguments.. The atomized individual, on the other hand, not liking an anomic life, seeks to unite with other human beings, but in this day, with the old links of heritage, family, faith, friends, and neighbors erased, looks tor community with those who share the coarsest similarities. Thus we have young people who invade the Dartmouth library wearing tee-shirts that display the motto, “I Love My Blackness”, and others who wear polo shirts and carry tiki torches in a parade chanting something unintelligible about (mythical) Jews.

Meanwhile, the Corporation State, which profits mightily from fungible producers and equally fungible consumers, sponsors a political circus show to distract the ignorant and gullible atomic persons who wander, stripped, shorn, and isolated, through the public square, from their devastating loss of patrimony.

But, how, really, does anyone work to undo this mockery of human interaction? Thanks to “urban planning”, the very structure of most citizen’s lives is far away from the (rural/agricultural) values which have been erased? Attempts to create urban local communities, in this century have either depended on sufficient luxury income to pretend this suburb is different, or on artificial and mechanical solutions which were worse than the previous state.

Fortunately, I live in a) a rural area, and b) have a front porch (and swing on which to perch). It is a luxury, and how many have this blessing? How many sophisticated urbanites would even think it is a good thing, to be desired? And, how many can the rural areas absorb without destroying what was once there?

Brian and David,

Lots of points to agree with. Also living in Rural America (for the first time) from my previous “sophisticated urbanite” ways, it seems I often come across a place that does not even recognize what it has, rather then embracing the beauty of the country life, I find people escaping to the city for “real” life or completely self absorbed in destructive addictions. Obviously a generalization, but it is common here in the South. There are a few gems out here (families) however I find them much more difficult to find then I would have expected.

Why question is: how does rural America regain a culture and a life not consisting of meth, poverty (of the soul more so)?

Good question, Tommy.

My explanation (or rationalization) may be entirely bogus, but FWIW, here goes.

TV.

Rather, that as the theory and practice of utilitarian individualism have erected barriers between human beings, technology has torn down those former barriers between cultures which once allowed (or promoted) regional and distinct local differences. “When I was a kid,” (sorry for the cliché, but it’s true) I grew up in an area geographically Northern and culturally Dixie. (Per The Nine Nations of North America theory.) The ways were even then changing, with only (mostly) AM radio stations and three TV networks (Four if you count PBS) available in my area.

No internet. No satellite TV. No niche faux-“communities” consisting of one person in Poughkeepsie and another in North Bend and a third in Evanston. Kids played outside all day without parents or police hovering nearby. One’s relatives were nearby, and frequently seen. Anyone who failed to go to some church or another was looked on with suspicion. To beggar a phrase, the village raised the child.

Now, people are culturally connected, via media, with the centers of public thought and consumerist lust. And isolated from those next to them. I have seen families sitting in the same room, talking into their smart phones and not with each other.

Toss in the lack of meaningful work as the economy has eradicated blue-collar jobs in favor of going overseas to seek cheap labor (in the name of utilitarian efficiency), the reluctance of human beings to become relocatable fungible assets in the maw of a corporate Mammon, and drugs are an inevitable result. And the Corporate States of America approve of this addiction, even as the World State of Brave New World approved of soma and sex to subdue its faceless masses.

How to change it?

Another John Westley preaching morality back into the backbones of America. (It is said his preaching averted a revolution in England that would have made the one in France look like a Sunday School picnic.) Failing to find Westley (or even Picard, Kirk, or Sisko), we should have to do the job ourselves. People in those afflicted areas voted for Obama twice for hope and change, and once for Trump. They have been disappointed on all fronts. Rather, betrayed on all fronts. Offer them that hopey-changey-thingy, show (not just tell) them it is possible, and they will go for it. Meaningful change means a revolution, and revolutions are waged by the hopeful, not those sunk in the despair of gin or opioids. Not an economic revolution, or a political one, but a religious one. A Christian one, not tainted by those leaders who have sold out for a crumb of power and prestige. A (if I may so describe it) Catholic one, which recognizes the unity between Christians. A Humane one, which does not discard the fruit of 3000 years of The Great Conversation.

As noted, my thoughts may be entirely off the chart for reality, but I honestly see no other way out. We’ve exhausted all the utilitarian means, other than genocide. (Don’t think some on the Right as well as the Left haven’t almost advocated such. What else does it mean when they say ‘those people’ should die and get out of the way of the New Economy?)

I have been doing a lot of reading around this issue lately, including in American Affairs and Deenan’s Conserving America, and I think the ancient concept (that used to be part of the fabric of Western thought via basic Christian theology and anthropology) of Disordered Desires is at the root of the problem. It sounds obvious. Unfortunately, the idea is now as alien as anything Valentine Michael Smith, ever attempted to “grok.”

We believe in Feelz, in “doing what you love,” following your passion, but don’t believe in wanting, desiring, what is Good and Right because those are alien ideas as well, and since we don’t believe in them we have no method to teach or train ourselves and others how to rightly order desire. The Imperial Self wedded to the Pursuit of Happiness–defined exclusively by that Self–means no limits, no boundary conditions on desire. Gone is even the shadow of “that we may delight in Your will and walk in Your ways” found in a common prayer of repentance and confession.

While “culturally connected, via media, with the centers of public thought and consumerist lust. And isolated from those next to them” spot on, and wonderfully phrased, another aspect of modern life also serves to accelerate the decay: specialization.

I was reading an article this morning by Spencer P. Morrison in American Greatness that looked at the overly domain-specific and path-dependence weaknesses of Comparative advantage theory. Morrison’s heading “Buying the Future We Should be Building,” really struck me. I know little of economics and trade, but if I understood the essay rightly, it seems to me that what we have done as both individuals and communities is the same thing America has done as a nation; that is, in pursuit of efficiency and increased productivity we have become overly specialized.

I was raised in the rural South and spent most of my life here, and one of the things I try to do, something that naturally flows out of rural life, is to not outsource my life. I try to do modest car repairs, cut my own grass, fix my leaking pipes, paint my fences, becomes broadly competent in Home Economics, basically.

A city lawyer, say, who works 100 hours a week in his specialty has to “buy rather than build.” Most people seem to think it’s good to outsource all the mundane, quotidian aspects of living, including child-rearing, but we lose something and sense something missing but can’t even begin to identify it. We make ourselves into a cog and then we remove the lubricant. Is it any wonder we grind down?

Tommy and David:

Both great insights here; thank you! While much could be said here, and I am sure that it could be articulated better by others, but I wonder if Tommy’s question about rural life not “consisting of meth and poverty” must, at least, regain an initial form of integration between the city and the countryside? I think Wendell Berry is illuminative here, as well as the work of Notre Dame’s Phillip Bess. Perhaps we should consider the land or the countryside not so much as being strictly or primarily in opposition to the city. Now, this is at least going to be conceptually first, although there are some who are already practicing some of its fundamental principles (I am thinking of Charles Mahron and those associated with Strong Towns, among others).

More needs to be done in this respect, and my comments are rather insufficient. This would be a great area to dive into with greater depth.

Brian,

I wonder if Tommy’s question about rural life not “consisting of meth and poverty” must, at least, regain an initial form of integration between the city and the countryside? I think Wendell Berry is illuminative here, as well as the work of Notre Dame’s Phillip Bess. Perhaps we should consider the land or the countryside not so much as being strictly or primarily in opposition to the city.

This is well said–but as always, easier said than done. Over the past two weeks I’ve been diving into the works of the sociologist Robert Wuthnow, and of the many insightful observations that his exhaustive, attentive listening to and looking at farming and small-town life provides, probably the most bracing to me is the fact that, environmentally, some parts of this planet are simply going to far, far less amenable to the kind of integration you refer to than others. The whole contemporary history of the American Midwest, and the moral perspective of the (overwhelmingly white) residents of the farms and small towns in that region, is defined by an oppositional, love-hate relationship between the land where people put down roots, and the cities which their children flee to for jobs and where they travel to catch touring Broadway shows. And this oppositional sensibility is frequently almost exactly the result of those small towns inability to find any integrated balance in their belonging, to make anything truly sustainable without opening themselves up to investments, to people, and to perspectives that run against the same mentality that led them to stay in the first place. It’s just a hard problem, that’s for certain.

Dear Professor Fox,

I am grateful for your comment! Your thoughts, along with your essay, are very illuminating with respect to the relationship between city and countryside. I could not agree more with you final sentence that “it’s just a hard problem.” Perhaps there is nothing more disheartening for our ears to hear than this reality, but it is the necessary ground for the possibility of actual coming together and doing something about it.

As an aside, I thoroughly look forward when your essays appear in FPR. It is a little mini-education in itself, so thank you.

This article and its responses are very close to what I have been thinking for most of my nearly seventy years, from my farm childhood with church, 4-H, and small county seat school system, through my formal education at the University of Chicago (where I became enthralled with Tocqueville) and my theological seminary studies at Vanderbilt Divinity School where a New Testament professor taught me to apply the teachings of Jesus and Paul as an explosive against the “technological myth” of our time, and where I heard Will Campbell, sounding more than a little like Wendell Berry, drop by to warn the students about the way the powers-that-be planned to use our higher education to destroy our biblical faith and family and community ties in order to further their agenda of separating individuals from the power of formative institutions and to make them into interchangeable cogs in the great machine of production-and-consumption. Campbell and Berry aren’t wrong. Neither was Tocqueville. And especially neither were Jesus and the Apostles. I have not yet made much of a difference. We must pray for clarity, for conviction, and for the lever, fulcrum, and place to stand.

Comments are closed.