This is awfully late but perhaps also timely (since the spat between Sohrab Ahmari and David French seems to have a long shelf life). What follows is the talk I gave at the Front Porch Republic conference in September, 2018. It is based on the forthcoming book, American Catholic: The Politics of Faith in Cold War America (Cornell University Press).

When Garry Wills and Brent Bozell Left The National Review Conservatism Failed (1968)

Liberalism is on the ropes and conservative Roman Catholics seem to be responsible for the bulk of punches thrown recently. The critiques of modernity’s twin political ideas – liberty and democracy – started first with Brad Gregory’s widely debated, Unintended Reformation (2012), a book that traced the woes of modern secular society (with its materialism, hedonism, pluralism, and unbelief) back to the disruptive effects of Protestantism. Next came Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (2016) who, though now Orthodox, appropriated Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue to argue that modern Christians needed to learn from Benedict of Nursia’s withdrawal from Roman society in order to save civilization and so form their own associations to transmit faith and morality to the next generation. Adding to this avalanche of criticism was Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed, who extended laments about modern society to argue, contrary to John Courtney Murray, that the founding of the United States was fatally flawed thanks to its Lockean and Hobbesian notions of human nature and political life. Those origins, for Deneen, inevitably spread liberalism’s inherently self-destructive “pathologies.” Listeners should not forget the flap at First Things over Pope Pius IX’s abduction of Edgardo Mortara in which the magazine’s heirs of Murray and Richard John Neuhaus tried to defend as religiously faithful an act as illiberal and anti-modern as removing a boy from his parents.

Most recently in this tag-team assault on liberalism was Kevin Gallagher’s piece at American Affairs on the so-called fusionism of Neuhaus and his circle of Roman Catholic public intellectuals who blended American political conservatism (especially free market capitalism) and the church’s social teaching. According to Gallagher, fusionists believed “their views were simply the correct application of Catholic principles to contemporary problems: the Church was to stand on the side of political and economic liberty against communism, and on the side of social and moral order against the sexual revolution.” Gallagher added that Neuhaus and company, whom Damon Linker ironically (only in hindsight) dubbed “theocons,” not only asserted that harmonizing American political and economic ideals with church teaching was possible but that “the mid-century American political settlement [was] the very embodiment of Catholic social teaching.” Gallagher also observed that this case leaned heavily on John Courtney Murray’s argument that the American founding depended on natural law principles that Roman Catholicism had always taught and that the church could employ to rescue the United States from 1968’s social, political, and personal dislocations.

Like the other Roman Catholic critics of liberalism, Gallagher argues that the attempt to synthesize the church’s teaching and traditions with American political norms was a fool’s errand. He writes, “the fusionists’ insistence on the compatibility of Catholicism and the American political tradition not only rings false, but also describes an ideal that few desire.” Instead, a younger generation of church members are reappropriating an older vocabulary – “with new watchwords ‘integralism,’ ‘dyarchy.'” In fact, Gallagher wrote, “the decline of fusionist Catholicism has cleared space for the revival of ideas” once suppressed in the era of Murray. “Instead of William F. Buckley and Richard John Neuhaus, young Catholics are reading Brent Bozell, and William Marshner” who offered an alternative to the fusionist option.

As it turns out, Gallagher’s argument might well have described the situation in 1968 in the offices of The National Review. That year, more or less, two of Bill Buckley’s closest colleagues, Brent Bozell and Garry Wills, sensed for different reasons that the conservative movement’s fusion of American political traditions and Roman Catholic faith were simply unworkable. Bozell left the magazine and his brother-in-law to form traditionalist institutions such as the magazine, Triumph, which would later nurture Christendom College. In contrast, Wills covered the politics of dissent and the Republican Party (with the election of Richard Nixon) to abandon conservative politics even as he remained in a post-Vatican II sort of way a loyal son of the church.

But as much as Bozell and Wills may have foreshadowed later critics of Neuhaus, George Weigel, and Michael Novak – the so-called neo-Americanists – they also exposed significant tensions in Roman Catholicism both in the United States and around the world. The fusionism that Gallagher describes was part of the warp and woof of Roman Catholic life in the United States well before the founding of National Review. Meanwhile, the Second Vatican Council’s approval of religious freedom on grounds argued by Murray seemed to vindicate the fusionism that American Roman Catholics had lived even if they had not always formulated it into essays or books. In other words, Americanism, the effort to adapt the faith to U.S. circumstances, went in the 1960s from a heresy to the standard outlook. Bozell and Wills saw the weakness of that development. But fusionism’s ongoing appeal, even down to the 2012 “Fortnight for Freedom,” was not simply the orchestration of well-connected Roman Catholic public figures. It was part of the American Roman Catholic experience going all the way back to the days when Baltimore was home to the only bishop in the United States.

From Heresy to Exceptionalism

A tendency to adapt Roman Catholicism to American life has been a prominent feature of the American church. James Hennesey’s formidable survey or American Roman Catholicism included the glowing praise that priests just after national independence sent back to Rome about the nation’s form of government. What was particularly noteworthy was the religious freedom that American norms granted to all religious groups. A letter from 1783 to the Vatican highlighted the “toleration that is allowed to Christians of every denomination.” John Carroll, who became the first American bishop, also praised the United States for placing all denominations on “the same footing of citizenship, and conferring an equal right of participation in national privileges.” This republican brand of Roman Catholicism, at odds with the Vatican, could not dominate the American church but was, as Jay Dolan argued in his book In Search of an American Catholicism, a recurring strain. Of course, the papal condemnation of Americanism as a heresy in 1899 by Leo XIII (somehow left out of catalogs of the church’s social teaching) put a damper on Roman Catholic praise for the United States. In fact, as late as the 1950s John Courtney Murray had to refrain from publishing his views on the compatibility between the American founding and Roman Catholic tradition because the United States granted political rights to error. That is, by saying that all denominations had the same standing, American government encouraged false religions and erroneous Christianities (read Protestantism) to flourish.

Nevertheless, even after Leo’s condemnation of Americanism, which was mild and designed more to settle disputes in the French church than to squash rogue elements in the United States (which to the Vatican was still a nation with little strategic import), the American church kept producing members who gladly aligned with national political ideals rather than any sort of integralist ideal. Here the explanation of faith is instructive from the “what-the-hell-is-an-encyclical”-Al Smith, the first Roman Catholic nominee for POTUS. The New York governor devised this confession of faith with the help of a priest decorated by both the French and American governments for service during World War I, Francis P. Duffy, which was published in the Atlantic Monthly:

I believe in the worship of God according to the faith and practice of the Roman Catholic Church.

I recognize no power in the institutions of my Church to interfere with the operations of the Constitution of the United States…

I believe in absolute freedom of conscience for all men and in equality of all churches…

I believe in the absolute separation of Church and State …

…I believe in the support of the public school as one of the cornerstones of American liberty.

Such Americanism was also the play book that John F. Kennedy used in 1960 when running for president to calm Protestant and secular fears about a Roman Catholic in the White House.

When William F. Buckley, Jr. started the National Review in 1955, he was hardly bucking the winds of a national church dominated by ultramontanists. Among the Roman Catholic laity who argued that American nationalism and Roman Catholicism were readily compatible were Phyllis Schlafly, Patrick Manion, a law school professor at Notre Dame who hosted a conservative radio talk show and became a leading figure in circles to draft Barry Goldwater, and Carlton Hayes, a Columbia University history professor who served as the U.S. ambassador to Spain during World War II, and became the first Roman Catholic president of the American Historical Association. Hayes’ arguments about the natural law origins of the American founding were, it should be mentioned, precursors to Murray’s views which prevailed at Vatican II. Buckley’s fusionism did not need an elaborate theological or philosophical rationale because Americanism was the air that members of the American church breathed.

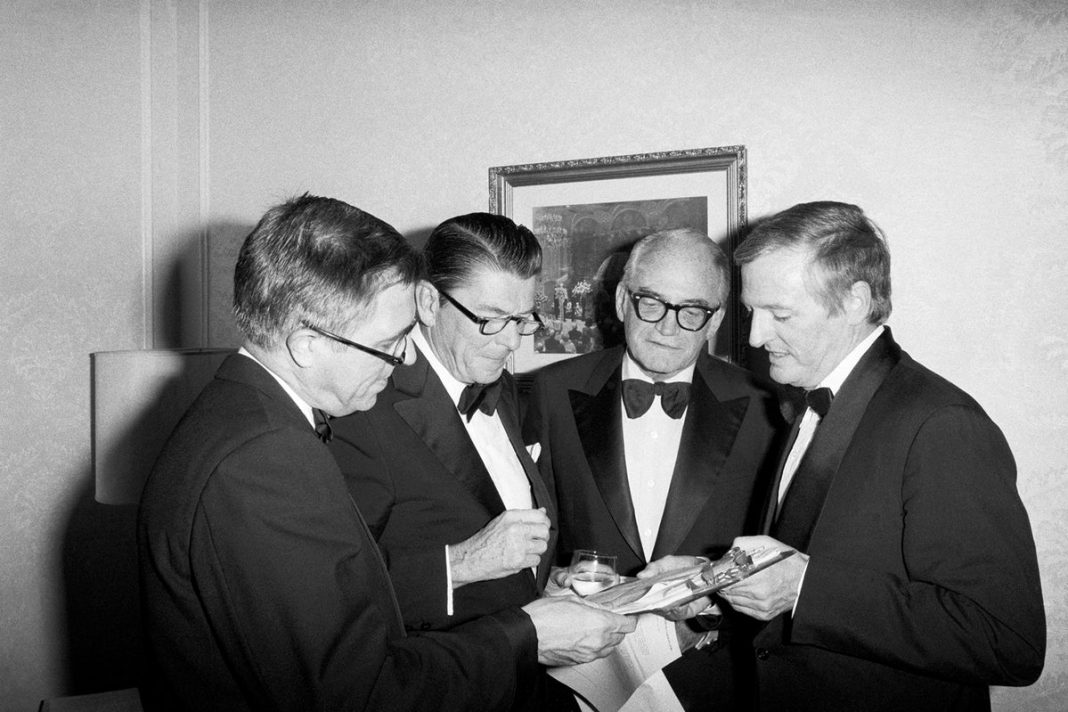

Bozell and Wills were part of Buckley’s most important colleagues at National Review, though Bozell’s ties to the editor went back to undergraduate days at Yale and to a co-authored book in defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Wills came later to National Review, while a doctoral student in the classics at Yale, his chief duty after leaving the rigors of Jesuit training for the priesthood. Both fit well with Buckley’s aim of recovering a conservatism that was true to the founding and sufficiently vigorous to combat Communism. But in 1968 the troika went separate ways thanks in part to disillusionment with the United States inspired by Roman Catholic convictions.

The first to go wobbly on fusionism was Bozell who became attracted to throne and altar conservatism during a two-year residence in Spain, starting in 1961 when he was also ghostwriting for Barry Goldwater, The Conscience of a Conservative. Then in 1966 he came out with The Warren Revolution, a book that echoed movement conservatism’s gripe about how the federal government, in this case SCOTUS, had departed from the Constitution. It also gave him a chance to survey the high court’s ruling on religion in public schools and Bozell used those decisions to complain about the way that the separation of church and state had barred God from public life. Along the way, Vatican II, which concluded business in 1965, provoked in Bozell sympathy for traditionalist opposition to the Council. The culmination of Bozell’s disaffection with fusionism was his decision in 1966 to start Triumph magazine. Initially, he attracted many of the Roman Catholics who wrote for National Review, and a mock-up of the new magazine prompted Russell Kirk to say, “Well, Brent, this is quite impressive, but there is already a magazine just like this . . . the National Review.” What Bozell found unsatisfying about his brother-in-law’s publication was that it sacrificed faith to the demands of secular politics. Indeed, Bozell’s insistence that government was legitimate only if it acknowledged its dependence on God explains John Judis’ verdict in his biography of Buckley that Triumph became “theocratic” at the expense of conservatism. By the time that in 1969 abortion became a matter of national debate, the differences between Buckley and Bozell were becoming apparent. While Bozell championed the papal encyclical, Humanae Vitae and railed against abortion, Buckley wondered if Vatican II’s teachings on freedom of conscience might give government and the faithful room to accommodate modern ideas about sex and fears of overpopulation.

If Bozell veered in a traditionalist direction during the disruptions of 1968, Wills moved toward liberalism in politics and the church. One indication of that parting of the ways came over Humanae Vitae. A long time student of papal authority, and author of one of the best books never read on the history of papal encyclicals, Wills argued that no infallible teaching was pressing on Roman Catholics, and that theologians had made concessions for married couples to experience sexual intimacy without an intent to conceive. That argument may have distanced Wills from Bozell, but where the break with Buckley came was over race and the Vietnam War. As a reporter for Esquire in 1967, after having failed to gain tenure at Johns Hopkins, Wills covered the race beat. He eventually produced the 1968 book, The Second Civil War, about race riots and police brutality, as well as admirable people on both sides of the law. Even so, this was not the sort of reporting that animated Young Americans for Freedom. Then with the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 and Wills’ book, Nixon Agonistes, his differences with Buckley and movement conservatives became obvious. There Wills registered a withering indictment of liberalism, its reliance on self-regulation, and its rosy view of capitalism as a “morally uplifting system.” Conservatives’ strict adherence to free market orthodoxy, according to Wills, left them incapable of responding to social crises with anything more than appeals to individual responsibility. The final straw was Wills’ sympathy with the brothers Berrigan and the Catonsville Nine, not for breaking the law but for understanding the folly of Vietnam. A decade later, Wills wrote Confessions of a Conservative and claimed still to be on the side of preserving “the cohesion and continuity of society” and a “concrete set of loyalties.” But Frank S. Meyer’s review of Nixon Agonistes for National Review had already sealed Wills’ fate. He was guilty, Meyer argued, of attacking “the American constitutional tradition, the heart and soul of contemporary American conservatism.”

The breakup of Wills, Bozell, and Buckley left the editor of National Review alone to carry the water for fusionism. Buckley backed Nixon in 1968 and steered conservatives away from George Wallace. He alone of the three held out for America’s political traditions. As Meyer explained in his review of Nixon Agonistes, the nation’s problem was not its political traditions but “the destruction of our Constitution and our tradition.” By 1968, Bozell and Wills could not abide that assessment. As John Leonard, an editor at the magazine described Wills, but in ways also applicable to Bozell, “He was not simply saying I disagree with you [Bill], but I am closer to God. A real moral issue was being thrown at them. . . . Garry was a soul. And Garry’s burned soul scared the shit out of them.” But Wills was not scary enough to topple the fusionism that ran deep in the veins of American Roman Catholics. Buckley carried fusionism on and eventually the pages of National Review became the place where other fusionists, like Richard John Neuhaus and Michael Novak tested their own versions of Americanism.

With the hindsight of fifty years, or even only twenty for the later iteration of fusionism at First Things, the harmony of Roman Catholic faith and American exceptionalism may look hollow or even blasphemous. The Gallaghers, Deneens, and Schindlers who have lined up to criticize those Roman Catholics who tried to be loyal to the church and cheerleaders for the nation certainly have lots of material with which to work. But such critics should also remember that fusionism was not merely a phase in the American church. It was the prevailing outlook going back to the Carrolls of Maryland. And it continues to be the understanding that informs the U.S. bishops and even Pope Francis. To explain in 2012 the first “Fortnight for Freedom,” the U.S. bishops maintained that freedom was the nation’s “special inheritance,” its mission to the world. They invoked James Gibbons, one of the leading nineteenth-century’s Americanist bishops, who in 1887 explained to the Vatican that “in the genial atmosphere of liberty [the Church] blossoms like a rose.” The bishops also quoted with approval Pope Benedict XVI who affirmed religious liberty as “the most cherished of American freedoms.” Such papal support for American politics finished second to Pope Francis’ remarks in 2015 while visiting the United States. In his address to Congress, Francis highlighted the political history of the United States with its famous beginning in the words of the Declaration of Independence, which were on the side of serving and promoting the “good of the human person and based on respect for his or her dignity.” So wholesome was the United States that Francis identified his own mission as presenting “the richness of [America’s] cultural heritage,” so that “as many young people as possible can inherit and dwell in a land which has inspired so many people to dream.”

If opponents of fusionism are going to prevail, they will need to do more than re-educate the readers of National Review and First Things. They will also have to change the minds of the very successors to the apostles.

Here is a much better article on French and Ahmari: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/06/ahmari-french-orban/591697/

Serwer’s best quote, and one that ALL social conservatives need to memorize:

“Black Americans did not abandon liberal democracy because of slavery, Jim Crow, and the systematic destruction of whatever wealth they managed to accumulate; instead they took up arms in two world wars to defend it. Japanese Americans did not reject liberal democracy because of internment or the racist humiliation of Asian exclusion; they risked life and limb to preserve it. Latinos did not abandon liberal democracy because of “Operation Wetback,” or Proposition 187, or because of a man who won a presidential election on the strength of his hostility toward Latino immigrants. Gay, lesbian, and trans Americans did not abandon liberal democracy over decades of discrimination and abandonment in the face of an epidemic. This is, in part, because doing so would be tantamount to giving the state permission to destroy them, a thought so foreign to these defenders of the supposedly endangered religious right that the possibility has not even occurred to them. But it is also because of a peculiar irony of American history: The American creed has no more devoted adherents than those who have been historically denied its promises, and no more fair-weather friends than those who have taken them for granted.“

Wrong, wrong, wrong. Serwer does not seem to grasp the very basic idea that there is always someone more liberal than you, and that liberalism has no internal mechanism whereby it determines how liberal is “too” liberal. Liberalism has worked because it has operated under an overarching consensus. It did not, however, provide or produce that consensus, which is now being eroded. Religious conservatives are simply the first to feel the effects of that erosion. As it continues other groups deemed “illiberal” or “unprogressive” will be affected. Anyone who thinks that the “religious right” are the only people that will be declared “old and in the way” is fooling himself. Already there are some old-style liberals starting to feel the heat for not being “progressive” enough.

So we should just return feudalism? If we can’t have perfect liberty today then we should never try to improve? What kind of a world do you want?

There is no such thing as “perfect liberty.” But even the imperfect liberty we had was only workable under a general consensus, including a consensus about what that liberty meant. That consensus is mostly gone, and there’s nothing to replace it.

So we return to feudalism? Go all the way to Falangist dictatorship?

To paraphrase a writer friend, I would be happy with the preservation and reform of something like the original American constitutional order. But like him, I’m not sure that the maintaining of the Republic is something that a lot of people care about anymore. They seem to be much more interested in their side winning than they do in living under some civilly agreed-upon consensus.

You want a return to slavery?

Yes, of course! And powdered wigs too! Sheesh.

Seriously, you do realize that the original constitution created a system that locked everyone who wasn’t already wealthy into perpetual misery? Everything good in life — education, leisure, the ability to make decisions and plans — depends on the individual person having money and time. Your world eliminates that for almost all women and almost all non-white men. Do you really think forcing most of humanity into peonage without their consent is a good idea?

I seriously do not understand you people at all. You speak of place and limits without understanding that it’s far different to have those limits imposed. You choose to live how how you live; the rest of us don’t and don’t like the restrictions. You can’t seem to spare one nanosecond to imagine what life is like for people who suffer in your world; apparently we just deserve to live in agony.

“I seriously do not understand you people at all.”

Now there’s something we can agree on!

https://mereorthodoxy.com/post-liberalism-racism/

Just gonna leave this here.

https://centerforneweconomics.org/envision/lectures-publications/search-by-author/

https://www.democracynow.org/

And these.

It’s ludicrous to suggest that critiques of liberalism are just an attempt to sure up white hegemony. Some of the most ardent critiques of liberalism have been non-whites.

But for the record, I don’t think Constitutionalism is the solution. There are plenty of understandings of place, limits and liberty that need not rely on Originalist readings of that document.

With all respect to both of you, Rob and Karen, I think you’re talking past one another.

Comments are closed.