I’m prone to say that the gardening year resembles nothing so much as a succession of heartbreaks, and while it’s possible that this sentiment reveals more about the gardener than the activity, I think there is a universal truth in this sentiment. What with pests, disease, bad seed, bad weather, poor soil, late frosts, early frosts, marauding squirrels, careless neighbor children, and the thousand other natural shocks gardens are heir to, there’s always something to be feeling bad about in the garden.

No matter how skilled the gardener, something is always going wrong, and it’s easy to take these failures personally. Losing the slightest herb plant can be a shock when one has nurtured it from seed; the demise of coveted crops like tomatoes or melons doesn’t bear thinking about. The gardener must, as a wise man once said in a much different context, “get used to disappointment.”

I say gardening is mostly about heartbreak, then, partly as a form of self-protection, but also as a recognition that unbroken success is not the gardener’s lot. Living systems like a garden don’t permit of failure-proofing. No matter how long you have gardened or how scientific your methods, drought, blight, and tomato hornworm yet lurk at your door.

It is in this context that I recently read the following quatrain in Eleanor Perényi’s delicious garden book Green Thoughts:

The kiss of the wind for lumbago,

The stab of the thorn for mirth,

One is nearer to death in a garden

Than anywhere else on earth.

Perényi is inclined to demur from this bit of doggerel, which parodies a sentimental poem about gardening by Dorothy Frances Gurney. She cites numerous examples of long-lived gardeners, arguing that gardening is a life-giving, not a death-dealing, activity. I can’t disagree; Perényi herself, I note, lived to 91.

Yet I think Perényi rather mistakes the subtext of the quatrain, giving it a more literal cast than necessary. Certainly, gardening can be conducive to long life, like any healthy, outdoor activity (provided the gardener applies sunscreen and avoids rickety ladders), but that’s not the point. We are near to death in the garden not because it’s a death trap, but rather because it’s a memento mori, a reminder of our mortality. The garden doesn’t kill us; it reminds us that we will die.

Modernity tends to insulate us from death—in human life it does this by segregating death to hospitals and mortuaries, but it insulates us equally on the vegetal level: public landscapes are kept pristine and freshly planted year-round, and the grocery stores are always full of ripe fruit. Should we so choose, modern people can move about a world where the spectre of decay largely has been hidden from us.

In fact, this is not a new problem; though it is perhaps made more acute in modernity, human beings have always tended to deny death. This is why the memento mori has a long history as a spiritual discipline and subject of devotional art. Whereas forgetfulness about death promotes heedless living, remembering our death calls us back to living as we ought, to repenting our sins and pursuing our ultimate hope. “Remember that you will die,” says the memento mori, “because you dare not go on living as if you won’t.”

The remembrance of death has been institutionalized in those churches that still observe Ash Wednesday and the season of Lent, a time of penitence and sharing in the sufferings of Christ in hopes of sharing in his glory. I tend to be forgetful of my death, to live as if I will go on forever and never be brought to account for my actions, so I find this annual reminder invaluable.

The annual heartbreaks of the garden serve to remind me of my mortality as well. Death is a regular feature of the garden year, from thinning the first seedlings of spring to enduring the last frosts of autumn. The gardener who must cut down a diseased sapling or pluck out an extra radish plant can preserve no delusion of endless youth and perpetual greenery. We observe death constantly as we care for our gardens, and indeed we may be called upon by the needs of the garden to deal out death ourselves.

Moreover the gardener, at least in temperate regions, lives with a persistent consciousness of times and seasons. Constant attention to the changing of the seasons also means constant attention to the progress of time, progress that bears us ever closer to our end. Perényi recognized this feature of the garden, writing in her essay “Autumn” in gratitude for the end of the garden year: “Heavier dews presage the morning when the moisture will have turned to ice, glazing the shriveled dahlias and lima beans, and the annuals will be blasted beyond recall. These deaths are stingless. I wouldn’t want it otherwise. I gardened one year in a tropical country and found that eternal bloom led to ennui.” Paradoxically, the coming of death to the garden was revivifying for Perényi herself. There is nothing so odd in this, really; denying death is a profoundly unnatural, thus alienating, position for we mortals to take. To accept that the garden tends toward death thus ought to revive us in our creaturely life.

Finally, the gardener knows viscerally that from dust we came and to dust we will return. All life comes from the soil. And for all that the soil teems with life—earthworms and bacteria, mycorrhizae and nematodes—it is also a place of decay. Healthy soil must include plenty of organic matter, which is to say, the dead: grass clippings and fallen leaves, the bodies of insects and the remnants of last year’s garden. The life of the garden—thus the life of the gardener who feeds upon it—arises from the dust of the earth and the decay of its previous inhabitants.

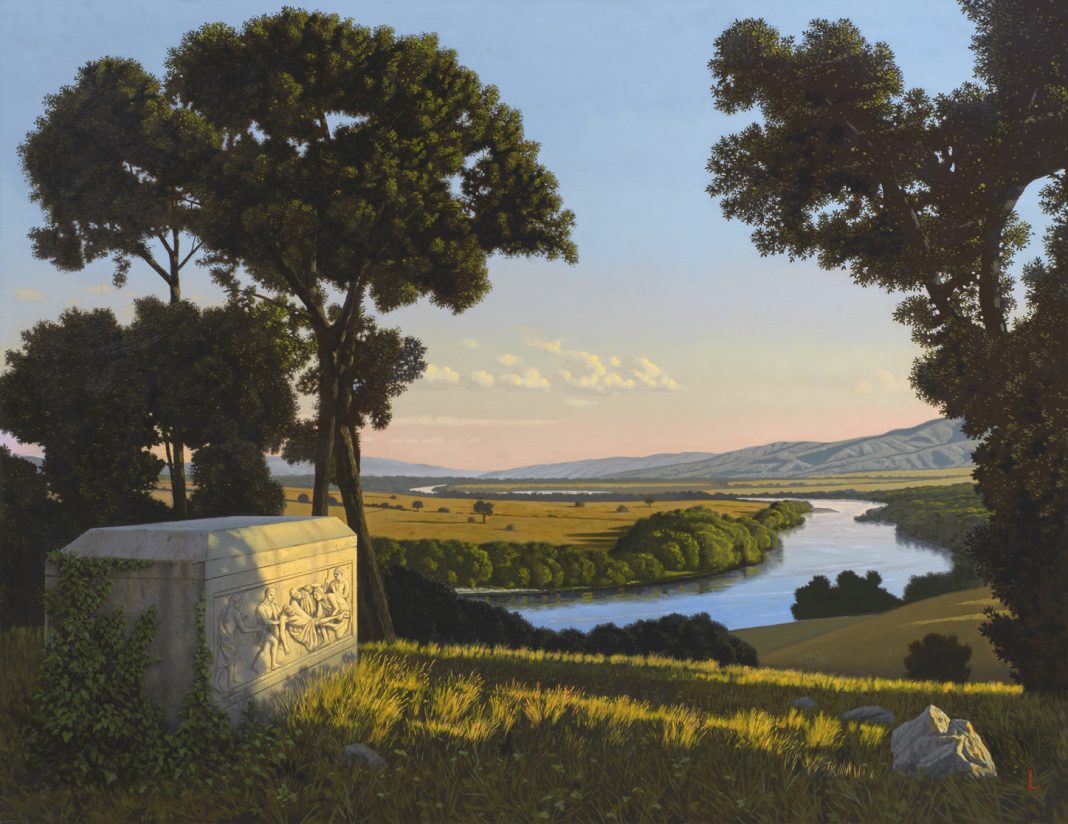

The imagery of the memento mori, which has a long history in art as well as the church, looks about like one would expect: skulls and skeletons, ashes and dust, black and purple drapery, flickering candles and wilted flowers. It may seem counterintuitive to propose adding the image of the green and verdent garden to this catalog of grim images, and so it is. But walk out into your own garden, if you have one. (Even a lawn will do.) Take a trowel, or better yet, two fingers and turn over some of the soil. Smell. Let that aroma be for you now a reminder that one day you too will rest under the earth.

In other words, gardening is the author’s religion? Poor guy, has no hope of an afterlife! Even in his own religion, each spring is a reminder of resurrection and afterlife.

Excellent thoughtful essay. Thanks

Nice work, Matt. I am reminded of many a lesson from the Bible that teaches the kind of regeneration our gardens and orchards demonstrate for us regularly. The seed must die in order for new life to emerge. This illustration of redemption is inescapable.

BTW, I’m another Nebrasaka boy, earned a BA in English, and transplanted to Missouri.

Carry a memento mori. Called to mind the ambiguity of the green man, this work of yours. Was reading Jones’ Anathemata, a few lines been working on for a bit. There’s a deep root in the culture, leaves of which spring up from time to time. Trying to learn to see them and affix them somehow, but not certain it’s possible. Thanks for the work.

enjoyed both reading your article and looking at the picture. Which river is that ?

Comments are closed.