America is at an awkward age. We are old enough to be embarrassed by our parents, but not mature enough to figure out what a healthy relationship with them looks like or how to understand their role in shaping our identity. We look into the mirror, hoping for and against resemblances.

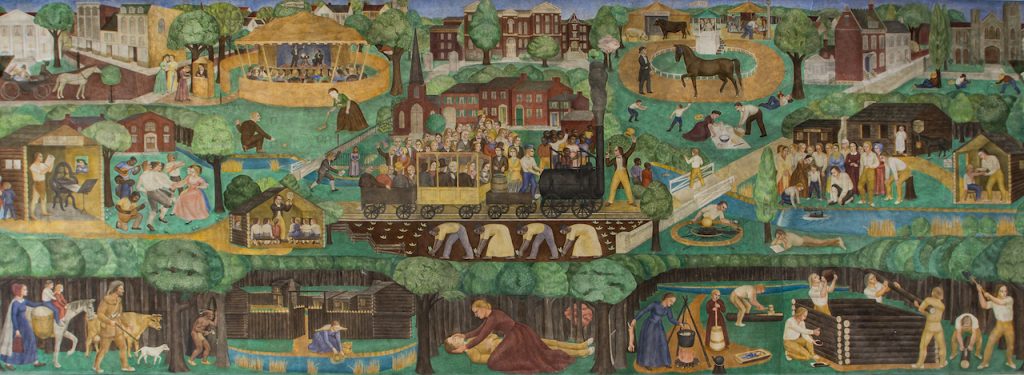

Our ambivalence about our ancestry has come to a head in the debates surrounding memorials and monuments and murals that reference our past and its people. In the last few years, we’ve had constant headlines about statues being contested or taken down. Many were symbols of the Confederacy, but others were associated with imperialism or with more ambiguously morally-coded people and situations. In 2015, Wendell Berry defended the O’Hanlon fresco in Memorial Hall at University of Kentucky. It was covered up when what some considered a realistic, if stylized, portrayal of Kentucky before Civil War was deemed by others to be romanticized, “painful and degrading.” Wendell Berry worried that if an accurate reminder of the past is too painful to be seen, we were very nearly in a place where “forgetting history” had become “the purpose of higher education.”

Many of the debates about murals and memorials invoke “history.” But what is history? According to historian John Fea, history is “the art of reconstructing the past.” History is the narrative we tell ourselves about the past, done within a specific discipline, with disciplinary norms and standards and evidentiary requirements. As Fea explains, “history explores and explains the past in all its fullness and complexity.” Properly speaking, most of the debated monuments and memorials are not doing history. For example, the Robert E. Lee statue taken down in New Orleans and statues like it may now be historic, but they do not “explain the past in all its fullness and complexity.” Rather, they are the product of collective memory and symbols of heritage. They invoke the past to celebrate a figure or a moment or to inspire or to cultivate remembrance. The work of heritage is not inherently bad, but it is not the same thing as history.

If both represent the past, does it matter if something is heritage or history? Heritage deals with heroes and villains, but history deals with human beings. Our society has often chosen heritage over history and has tried to turn flawed men (and some women) into heroes, but their humanity betrays them. If heritage is held too tightly, there is no room for the facts of history. The outrage of others produces more outrage for those who would rather deny the complexity of the past than confront it. Some Americans today seem to believe, like Plato, that a country needs a founding myth. But we are not fictive inhabitants of Plato’s imagined Republic, we are a real country, built by real people. In his recent book, The Soul of America, Jon Meacham writes that “to know what has come before is to be armed against despair. If the men and women of the past, with all their flaws and limitations and ambitions and appetites, could press on through ignorance and superstition, racism and sexism, selfishness and greed, to create a freer, stronger nation, than perhaps we, too, can right wrongs and take another step toward that most enchanting and elusive of destinations: a more perfect Union.” Heritage can do many things, but it will never help us fully understand the past and build upon that past for a better future.

The reason so many symbols of heritage are falling today is because our public memory has failed to be sufficiently collective. The Robert E. Lee statue in New Orleans stood for many years, but during those years many of the people of New Orleans had little ability to shape the public space. According to Wynton Marsalis, his great-uncle walked past that statue almost every day and resented it. But it was not until the 300th anniversary of the city that the descendants of slaves had the political power to have it removed. As more voices are being heard, it is clear that many of the “symbols of our past” reflect only the perspectives of some of us. I recently met a gentleman around seventy, who bemoaned the fact that some people want to focus on the bad in our country’s past. He added “and they act like they were bad people because they owned slaves. We had a vested economic interest in slavery.” His “we”—his Americans—does not seem to include anyone who may have been enslaved. We might also wonder what would be his reaction if someone had a vested economic interest in owning him as a slave. He has failed to imagine himself in the shoes of his fellow citizens. That lack of imagination is why so many attempts at collective memory are contentious and rejected and why the fabric of our nation is so frayed. Until we understand our past, we cannot step out of its shadow.

Taking down a symbol of heritage neither erases the past nor necessarily distorts the historical record—in fact, removing such memorials can clarify our fraught history. But there are also threatened objects which attempt to document the past in its complexity and not simply celebrate it. Just recently a mural about the life of George Washington at a San Francisco high school narrowly escaped destruction. The New Deal mural depicted Washington’s reliance on slave labor and his negative relationship with Native Americans—it did not merely represent a triumphalist narrative. But it still made some people uncomfortable and it did get covered up. This case is similar to that of the O’Hanlon fresco at University of Kentucky that Wendell Berry wrote about. Here the issue is not denial of some aspects of the past, but discomfort for altogether different reasons. Not everyone wants to be reminded of slavery on their way to class, even if they acknowledge its past. This is especially true for those whose forebears were most negatively affected. How should uncomfortable art which acknowledges the complexity of the past be handled?

We might look to the fate of the O’Hanlon fresco for something like a solution. Today it is visible to the public. The University of Kentucky ultimately decided to add another mural to the space so that multiple viewpoints were represented. The past cannot be sanitized, but it can be contextualized. Challenging art which documents the past can be put into proper context—through labeling, accompanying materials, representation of other viewpoints in close proximity, etc. Location is itself an important context. We must choose the right spaces for challenging public art that deals with complex and sometimes painful pasts. We neither can, nor should, avoid all that is painful in the past. As Abraham Lincoln said, “we cannot escape history.” But we can find ways to present the past in its complexity that will be engaging and edifying for all of us.

When it comes to existing art, we have many options other than simply leaving everything unchanged or tearing everything down. The Natural History Museum in New York City just decided to build an exhibition around its Theodore Roosevelt statue and to allow the public and the debate around the statue to take center stage. “Addressing the Statue” provides a space for acknowledging both Roosevelt’s personal flaws and his contributions to the museum and tries to allow many different voices to be heard. Around the country, additional labels may be added to existing statues or memorials, providing more context. In many states of the former Soviet Union, statues of Stalin and other Soviet heroes were torn down but many now reside in special parks. They have become objects of history rather than tools of heritage. Monuments and memorials in the United States can move into museums, too, as artifacts. People may also choose to display on private property what the public is no longer interested in supporting. The public could also choose to create new art, which is more reflective of our shared past or which attempts to address the past in more nuanced ways.

It is worth remembering that our forebears did not suffer from an over-veneration of the past. In the Declaration of Independence, the rebellious colonists suggested that when government did not serve the aims of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, “it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it.” Thomas Paine, whose writings inspired George Washington and the Continental Army, argued that each generation should be free to determine its own course. We have never been Edmund Burke’s traditionalists. Each generation has been a new iteration of Walt Whitman’s “O Pioneers” and has sung its own “song of myself.” In advance of the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln told Congress in 1862 that: “The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise—with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.” Disenthralling ourselves from the past is an American tradition, and gaining a clear-eyed vision of the flaws and achievements of previous generations is itself part of our heritage.

“…many of the ‘symbols of our past’ reflect only the perspectives of some of us.”

ALL of the symbols of our past reflect only the the perspectives of some of us.

Is “reflecting our perspectives” even the purpose of symbols of our past?

The reference to Soviet monuments is jarring. Please tell me you don’t see any moral equivalence between statues of Stalin and murals of Washington. Because very, very few people are going to be willing to get on that train…

The Taliban blew up 1500 year old statues of Buddah carved out of a mountain. How is spray painting over a antebellum mural or proudly destroying a founding father’s statue any different? These people aren’t adding context to the past. They are seeking destruction of the past.

I understand why Lee statues evoke such emotions, but where does it end? If the NY Times 1619 Project is any indication, it ends with the complete destruction of American history. And if our shared history (however flawed it may be) is destroyed, our mythology reduced to rubble, what binds us as 1 people any longer?

I had thought the consensus view of this site is that the Paine/Whitman strain of American thought you reference is madness and at the heart of both our national dissolution and rapaciousness. Your overall point in the essay is fairly sound but this justification will lose this audience.

I agree with the distinction between “heritage” and “history” which Dr. Stice makes, but I agree with Robert that invoking the transience/disenthrallment supposedly at the heart of the American project is not a persuasive argument.

I appreciate this site for the fact that it publishes essays as thoughtful as this. I don’t feel qualified to comment on the Paine/Whitman philosophy, but to see even an attempt to articulate the nuance between heritage and history is refreshing. To me, it is that nuance which is so sorely lacking on both of most contemporary debates, including those about public monuments.

On the other hand, I don’t find nuance an acceptable justification for displaying monuments to the Confederacy. They were the enemy and they lost the war. Should we have erected and continue to venerate monuments to King George, General Cornwallis, and other British leaders because they are part of our history?

The behavior of those who deface, or forcibly remove these monuments might not be civil, but that’s not an adequate justification to let them stand. It should be a call to address our shared history with humility, honesty, and civility.

You seem to confuse we with they. “We” didn’t put up the monuments – “they” did, so, no – we do not have to put up monuments to King George or Cornwallis, but “they” did want to put up monuments to their men, leaders, and struggles. As a man, raised in the West and the North, but now living in the South who is descended from various Union infantryman who survived the war, were killed in combat, and died of disease, I have no problem with that. “They” are not my enemy and you will find many civil war contemporaries who actually fought in the war with far more forgiving attitudes toward “them” than our new enlightened scolds can muster. I bridle at at the destruction of old things and I don’t think my ancestors cretins because they did not hold the views of the present. I suspect if men on both sides of the Civil War could see what this country has become, they both would have thrown down their muskets and rifles, thinking this new Babylon not worth the cost of their lives.

I have no interest whatsoever in visiting a politically corrected Gettysburg or Antietam or Chancellorsville.

And the “You lost, get over it” take on the C.W. is ludicrously simplistic.

Elizabeth: I was a doctoral student in history at UK when that memorial was still in its original state. Based on that experience, I’d offer the following:

One of the depressing things about the “discussions” over the memorial, which were endless in the student newspaper, as I recall, was how fundamentally misbegotten they were. Even the Basically, it was just “we can’t erase the past” versus “some of our past was icky,” replayed over and over. In the abstract, I don’t disagree with your argument that contextualizing is a good thing. However, if the original arguments never remotely got into serious, sophisticated consideration of what history is actually for, then what are the prospects that contextualization will achieve all that much? Because we now lack anything like a cultural consensus that provides meaning to historical objects, what we’re then left with is “well, here’s one interpretation” and “now here is another interpretation,” which is an exact replica in public of the historiographical legacy bequeathed by that agglomeration of arguments known as postmodernism.

I don’t disagree either, with your (Nietzschean–in “Use and Abuse”) invocation of the positive good of forgetting things, of moving on, but at the same time, I think that contextualization as a strategy for fruitful discussion of public history is more likely to illustrate a dialogue of the deaf than it is to actually get anywhere.

What say you?

Comments are closed.