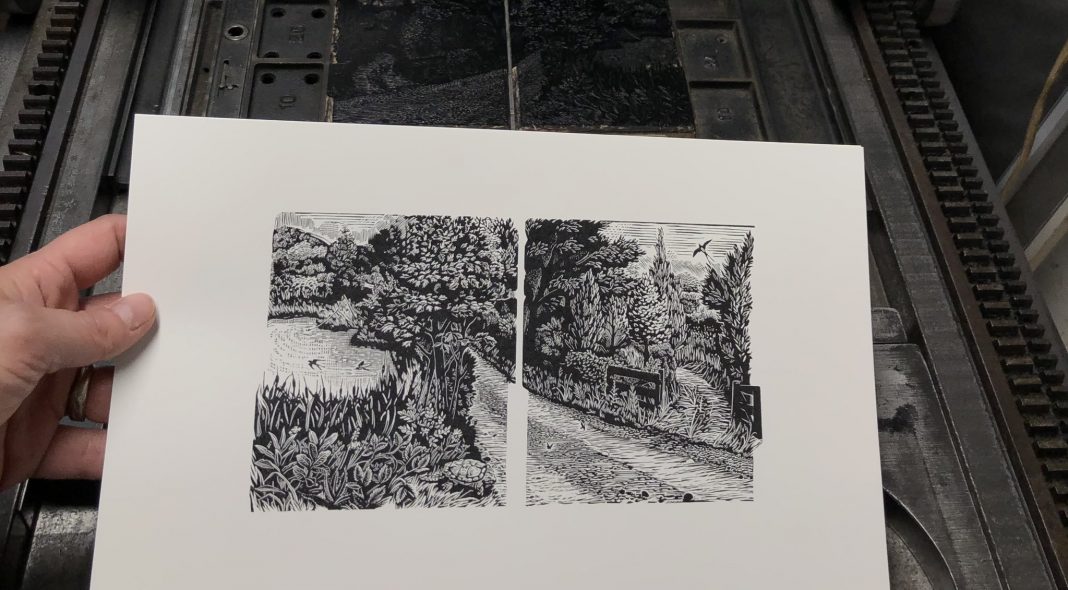

In the fall of 2018, Threepenny Review published a new short story by Wendell Berry: “The Great Interruption: The Story of a Famous Story of Old Port William and How It Ceased to be Told (1935-1978).” This story has now been published by Larkspur Press in a beautiful edition with wood engravings by Joanne Price (the photo above is of the book coming off the press). If you can get your hands on it, you won’t be disappointed.

At first, the story seems to be a humorous tale, something in the vein of the Tol Proudfoot stories. In 1935, Billy Gibbs, son of Grover and Beulah, is a thirteen-year-old with a love of adventure. So while he is often needed to work alongside his father, he takes what opportunities he can to explore the freedom of the woods around their home. Hence on Sunday afternoons, he enjoys fishing “the Blue Hole on Birds Branch.” It just so happens that across from that hole is a brushy fencerow. On one of these Sunday afternoons, a car pulls off the road and turns behind this fencerow where it parks for several hours. Billy is curious, but he can’t get close to the car without making himself visible, so he returns to his fishing until the car quietly pulls back onto the road and Billy recognizes the driver as a local politician, a certain Forrest La Vere, who is accompanied in the passenger seat by a well-dressed lady. (Grover and Beulah used to be tenant farmers on a place owned by Forrest’s relatives, and readers of stories like “Sold” and “Burley Coulter’s Fortunate Fall” know more about these families.)

The car returns to the fencerow the next week, and this weekly ritual piques Billy’s curiosity. So the third week, Billy perches himself in the branches of a box elder that stands above the car’s mysterious hideout. When the car arrives this time, Billy watches as the man takes the back seat out of the car and sits on it with his lady friend. The only way to describe what happens next is by quoting the narrator: “What followed Billy had seen enacted by cattle, horses, sheep, goats, hogs, dogs, housecats, chickens, and, by great good fortune he was sure, a pair of snakes. And so he was not surprised but only astonished to be confirmed in his suspicion that the same ceremony could be performed by humans.” When Billy scoots along the branch to get a clearer view, however, the branch cracks, and Billy finds himself falling—while clutching several branches—onto the back of the occupied gentleman.

Billy loses no time in making his escape. As his fall had been broken by several intervening branches, however, no physical harm had come to the couple, and he is chased furiously by La Vere until Billy finds a bramble patch to scramble through. Billy keeps this story to himself for several years, but after he grows into early manhood, he relates it to Burley Coulter one night while they are out coon hunting together. After that, the story quickly spreads through the Port William membership, recited chiefly by Burley and Billy’s father Grover: “‘He done it, she done it, they done it,’ said Grover, who loved grammar mainly for its comedy.”

The Great Interruption, as the story came to be known, had particular meaning for those who lived in this place and knew the people involved. As Berry explains,

the story belonged richly and complexly to Port William, pertaining about equally to its geography and its history. It was a part of its self-knowledge. It meant in Port William what it could not mean, and far more than it could mean, in any other place on earth. The ones who told it and the ones who heard it knew the abandoned field and the brushy fencerow at the lower end of Birds Branch. They knew the Blue Hole and the big briar patch. They knew Billy Gibbs, the boy he had been and was. They knew the nature and character of box elders. They had kept the stories of a greedy and miserly, eccentric and amusing family known around Port William as the Leverses, who down at Hargrave were a family of greedy aristocrats known as La Veres. The tellers and hearers of the story understood in an ever-renewing instant the entire signification of their vision of the august Forrest La Vere conjugating the commonplace old verb upon an extracted backseat in a weedfield.

As this description implies, the story lived in a delicate ecosystem, a rooted community that shared a complex web of common knowledge. And this web was torn asunder in the years following World War II as farming machinery and economic changes drew the young people of Port William far from home. Thus Berry’s story is actually about two great interruptions: the first forms the occasion for Billy’s tale, and the second is how, as the title has it, the tale “ceased to be told.” To put this in the terms favored by some theorists of contemporary social discourse, the story is a victim of “context collapse”: it no longer has a rich, shared culture in which to resonate as it is passed between teller and hearer.

The story’s title indicates it takes place between 1935 and 1978, and this latter date marks the year between Burley Coulter’s death and that of Grover Gibbs. One day during this year, Andy Catlett—Berry’s autobiographical narrator of the story—is talking with Grover about the state of affairs in Port William, which revolve around “the departure of the people and the coming of the machines.” Andy comments that “‘the poor old ground is going to suffer for it.’” Grover’s reply, which forms the conclusion of the story, is sobering: “‘Honey, I know you know. The hurts ain’t all just only to the ground.’”

Like many of Berry’s stories, this one can be read as a moral fable. Despite their obvious differences, the two interruptions share a set of rough analogies. For instance, what is interrupted in both cases is a kind of off-the-books conviviality—an illicit conjugation, as it were, or an amateur meaning-making. Neither the couple on the car’s seat nor the membership of Port William are above reproach, though obviously the latter includes more moral exemplars than the former, but both are eroded by the professionalization of a technological, industrial economy. Port William’s stories ceased to be told because they “were being replaced by the entertainment industry, and so it was coming to know itself only as a ‘no-place’ adrift with every place in a country dismemoried and without landmarks.”

Moreover, the interrupters in both cases also share similarities. Andy narrates Billy’s thirteen-year-old personality in ways that echo Berry’s descriptions elsewhere of American culture. Billy’s life, Andy explains, “would have been simple if he had been only lazy—or, as he himself might have said if he had thought to say it, only a lover of freedom. But along with the wish to avoid work, his mental development brought him also to the wish to be useful to his parents and to work well, especially if an adult dignity attached to the work. And so he was a two-minded boy.” Andy elaborates on the result of this two-mindedness: “And so he grew up into usefulness and a growing and lasting pride in being useful, but also into a more or less parallel love of adventure and a talent for shirking.”

In this respect, Billy represents the American tradition that Berry has narrated in books like The Unsettling of America, a tradition divided between boomers and stickers, exploiters and nurturers. And of course, as Berry points out, these terms name “a division not only between persons but also within persons.” Or, as he puts it in “The Conservation of Nature and the Preservation of Humanity,” “All of us, I think, are in some manner torn between caring and not caring, staying and going.” Billy Gibbs is torn in this way, and it is his voyeuristic curiosity that leads him to leave his fishing pole and climb into the box elder on a Sunday afternoon. Eventually Billy and three of his four siblings are drawn away from Port William, so Grover knows from painful personal experience that the departure of a community’s people doesn’t only hurt the soil.

In both cases, then, Billy is the interrupter, but in neither instance should he be seen as the primary agent. As Eric Miller wrote in our correspondence about this story, “The affair was bound to be broken or else a breaker of other at least more whole things (marriages, families, souls). And as the affair inevitably would cause destruction, so the ‘neighborhood of Port William’ didn’t really stand a chance, either, against infidelity.” Billy, like the rest of the Port William membership, is caught up in larger historical forces, forces which limit his range of available options. In that sense, then, Berry’s story is a tragedy. It nevertheless rings with humor and bears witness to a hope that those who are hurt by these forces can continue to narrate alternative economies and imagine communities that stand against these deracinating tendencies.

Berry’s new story, like much of his fiction, reminds me of Donald Hall’s admonition to “spend quick lifetimes telling old stories while we stand on dirt thick with the dead.” “The departure of the people and the coming of the machines” have interrupted the lives of many places and communities, and Berry’s stories bear witness to the good, though flawed, conviviality that has been thus eroded. Perhaps the best we can do now is to “begin again with what remains”—to tell one another the stories of those who have shared our places.